CHRISTIANITY AND JUDAISM often come under attack from the green movement for their supposed anthropocentrism and disdain for other species. There are certainly versions of both religions that show a troubling lack of concern for non-human nature. The current alliance of Christian fundamentalism and far-right politics in the United States seems to pose unprecedented threats to the environment. Fanatics who believe in an imminent ‘rapture’, when true believers will be wafted naked into the sky while infidels are visited with plagues, care little what devastation is wrought upon the Earth in the meantime. Why not despoil pristine wildernesses when time is in any case short?

This is extreme stuff, but the deeper charge, originally laid by Nietzsche, is that antipathy to nature is right at the heart of Christianity. Christianity represents a turning away from nature – from sexual nature in particular, but also from the Darwinian laws that ensure that the strong triumph over the weak. Christianity rejects the Earth and earthiness in favour of Heaven and saintliness (though it might be hard to detect any of the latter in those who most publicly represent the ‘rapture’ movement).

This charge is not without foundation, but Christianity’s turn away from nature has more to do with St Paul and St Augustine than with either the Old or the New Testament. The obvious place to start is the Book of Genesis. God’s command in chapter one to Adam and Eve that they “be fruitful and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth” has been anathema to generations of environmentalists. But what does subduing the Earth and having dominion over living things mean?

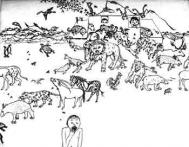

Having dominion over other living things may put humankind in a godlike position, but it also implies a duty of care. Having dominion over creatures is quite different from exterminating them. Even when God is so disgusted with the wickedness of the Earth and the animals he has created that he repents having made them, he stops short of extermination. His instructions to Noah for building and stocking the ark are extraordinarily detailed and specific – specific, that is, in every sense: not just explicit and particular, but also relating to specified things and also relating to biological species.

“Of every living thing of all flesh, two of every sort shalt thou bring into the ark, to keep them alive with thee … of clean beasts and of beasts that are not clean, and of fowls, and of every thing that creepeth upon the earth.” The Lord, while destroying the corrupted life on the Earth, wishes to preserve all species, both “clean” and “unclean”, in order to “keep seed alive upon the face of the earth”. Thus Noah is instructed to bring food on board the ark, not just for himself and his family, but for the animals too: “it shall be food for thee, and for them.”

Noah obeys to the letter, and the ark with its human and non-human cargo rides out the flood. God remembers him and the animals with him, and causes the waters to be “assuaged”. When the ark is beached on dry land, the Lord establishes his covenant, not just with Noah and his family, but with the animals: “neither shall all flesh be cut off … neither shall there any more be a flood to destroy the earth.” The rainbow is set in the sky as a “token of the covenant which I make between you and me and every living creature that is with you, for perpetual generations… While the earth remaineth, seedtime and harvest, and cold and heat, and summer and winter, and day and night shall not cease.”

Now once again we are faced with a flood: a threatened rise in sea level of up to seven metres, if the Greenland ice melts, which would indeed cause an inundation of Biblical proportions, threatening cities such as London, New York, Shanghai, Hong Kong and their hinterlands. But as Nietzsche once again foresaw, this time we cannot blame an angry God. It is we ourselves, already extinguishing species at a thousand times the background rate, who are proving less merciful than the famously vengeful Yahweh of the Old Testament.