THE ANCIENT GREEKS looked at Nature and saw a grand display of divinity. They saw the vitality of Pan in the countryside and in wild animals. They saw the pristine sense of Artemis in the purity of an unviolated forest. They saw the beauty of Aphrodite in the shimmering light of a rising sun on an ocean or a lake, and in the multifarious colours and shapes of a garden. They saw the mysterious dim brightness of Hera and Hekate in the moonlight on a dark night and in the sounds of birds and animals stirring the night with fright and wonder. They built shrines to these spirits they encountered whenever they ventured into Nature, and they told stories of them and painted images of them.

Renaissance philosophers said that you don’t have to be pagan to appreciate the spirituality of Nature. These various gods and goddesses are facets, they said, of the God many honour as the monotheistic source of life and meaning. In other words, you see God when you stop to wonder at a copper sunset or a misty moon. Nature is the avenue towards nurturing your spirit. It is the way in which the divine most powerfully shows itself.

There is a tendency, even among environmentalists, to adopt the 20th-

century way of seeing Nature, as a source of material commodities needed for the heroic building of culture. But that isn’t sufficient motivation for preserving Nature, because it doesn’t address our essence: what we need to survive as humans. We are people of body, soul and spirit. We need constant feeding of our vision, moral

sensibility and piety, and if Nature is at all diminished, our spirituality goes into eclipse.

The Greeks also revered the Earth as Gaia, a spirituality that echoes softly whenever we use the words geography and geology. Their Gaia is not only an organic mechanism but also a spiritual entity; a being with a life of its own and a very particular identity, not to be confused with any other planet. Renaissance philosophers said that the Earth is an animal; not just an organism but a being that can be loved and needs our care.

The Greeks prayed a psalm to Gaia that, among other things, says,

Both beautiful children and beautiful harvests come from you, The gift of life and taking it back, for all of us, is your doing. A happy person is one you favour. That person has it all.

Today the very existence of Gaia is threatened, and so it might be a good time to return to the old practice of praying to her – God manifested as the Earth. Spiritual practice maintains a deep memory of what is most important in life. It sustains an honest and intelligent brand of piety that keeps us devoted and reverent. It sustains our ethics on a day-to-day basis and gives us the inspiration we need to honour the Earth and thereby protect it.

A short prayer is effective: “Dear God of the Earth, thank you for giving me life every minute of every day.” Or, perhaps a bit more daring: “Spirit of the Earth, Goddess, I am devoted to you and honour you with my prayers and actions.” These two tiny prayers are much in the spirit of the Greek hymns to the goddess Earth.

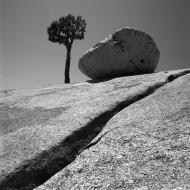

You could easily set up a small shrine focused on a special rock or grove of trees. You could get an artist to create an image of Gaia, earthy and timeless, and place it in your town for remembrance and inspiration. Keep it flourishing with gifts of flowers and oils. Flowers are the artwork of the Earth, and oil signifies a raising of the ordinary into the spiritually significant.

People might dismiss your effort as New Age fluff or pagan witchcraft. Take the criticism as a sign that what you are doing has some life in it. It’s unsettling and it contradicts the sleepy unconsciousness of the time. Use a style that reflects the noble, timeless, earthy, unsentimental, complex nature of the planet.

I BELIEVE THAT it was a mistake in Western culture when the monotheists decided to split with the pagans and then demonise them. We lost a spirituality of Nature. Devotion turned away from the Earth and focused on a point infinitely far away. Much spiritual literature and prayer around the world tells us that we can find God deep within the world and even within ourselves. Christians call this the mystery of incarnation: spirit and matter as one thing.

As long as we keep spirituality and the material world separated, the Earth will be threatened. A secularised planet will remain in our minds a commodity rather than an awesome presence. Of course, as long as the planet, our mother, is a spiritless orb of materials, we too will be commodities to medicine, to economics, and to politics. We will not be children but products of the Earth, objects easily manipulated and dispensed with.

For a flash of time in Western history, Renaissance philosophers spoke of a human being as something divine. The great theologian Nicolas Cusanus used the bold phrase deus humanus: a human god. He was a much honoured cardinal at the Vatican, and yet he could reconcile pagan and monotheistic theologies. Environmentalists and

visionaries today face a similar task: to return spirituality to the Earth, grounding our spirituality and spiritualising our ground.