BLINDED BY EVENING rays of sunlight, I finally arrived at the dilapidated YWCA hostel in Ooty, Tamil Nadu, the end of my long journey. I have came to spend time with an extraordinary woman who has started to transform this district of Southern India through nurturing, love and respect for the Earth and for the people to whom this land is native and sacred. You could say that, at seventy-three years old, she is in the prime of her life, with an infectious energy and charisma, and above all the belief that change is possible through simple means. As this quote by Lee Iacocca hanging at the entrance to her office reveals, “We are continually faced by great opportunities brilliantly disguised as insoluble problems.”

Ooty was the ‘Queen of the Hill Stations’ and capital of this once fertile region of Southern India. The Nilgiri Hills are a small range of undulating grassland uplands and shola forests about twenty by thirty-five miles in size. This ecosystem worked undisturbed until the mid-19th century when British settlers arrived to found the tea industry; subsequently, vast tracts of grasslands and shola forest were cleared for the satisfaction of colonial afternoon pleasantries. That’s how it was, and ‘snooty Ooty’ gained its reputation as a respectable place to retire to during the hot Indian summer months.

Traditionally the Nilgiris region provides most of the water for Southern India; during the monsoon, rainfall collects in the rivers and lakes and then winds its way down to the plains of Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu. This small and unique upland is full of complex ecosystems related to the five main ecoclimatic zones. To the south and west are the wet sub-tropical slopes; to the east, the dry, rain-shadow valleys. These highly localised and differentiated areas are home to many different plant communities – some with distant links to Himalayan species hundreds of miles to the north. Many, including extensive varieties of balsam, are unique and are found only here with their brilliant flower displays after the monsoon rains. This variety of flora, as well as the diversity of insects, birds and mammals, has led to a recommendation that the Nilgiris should be one of the first protected world biospheres.

Unfortunately, nearly 80% of the original environment has been destroyed by encroachment or ignorance of its value. More than 60% of the grassland has disappeared. This grassland had acted as a great tank, taking water from the mists as well as rains and releasing it slowly through the shola tree roots all year round. Much of this grassland has now been covered with thousands of acres of destructive forests of eucalyptus and wattle, as well as the green deserts of tea plantations. The thin soil layer on much of the hills has been extensively damaged by recent chemical systems of farming. Soil salt levels are often 20% higher than they should be due to excess fertiliser, pesticide and herbicide use. Soil life is generally extinct in cultivated areas, and farmers owe 30,000,000 rupees to fertiliser companies. On top of all that, global warming is changing monsoon seasons, and whilst I was there – the summer – it was rainy and foggy, which is highly unusual!

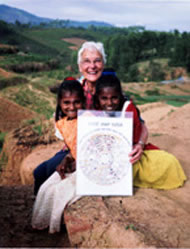

THIS IS THE environment that Vanya Orr has been seeking to radically change for the last eleven years. She has a strong connection with the area: her family first came here in 1824. Her work specifically addresses issues of sustainable farming, health, livelihoods and environment. It is based on a holistic concept where each area interrelates with the others. Last year Vanya set up her own independent non-governmental organisation called The Earth Trust, which now employs twenty staff.

One of her major goals has been to teach biodynamic and organic farming to local farming communities, and to organise a system by which produce can be brought to market and sold profitably. To underpin this work a series of Organic Training Centres (OTCs) have been established in nine villages in the region, and the OTC farmers now have an association called Biodynamic Organic Growers Association in Nilgiris (BiOGAIN). In the near future, a producer marketing company will be set up with farmers, buyers and The Earth Trust as partners. It will share a common vision of collective responsibility for the Earth and support for its healing. There is also a fast-growing schools programme where pupils learn about soil preparation, organic fertiliser, biodynamic planting and recycling, with the final reward of growing their own produce, an important investment for the future.

The Earth Trust is also supporting the often neglected and traumatised women in the village communities. A Village Women’s Health Programme has been set up which involves all levels of healthcare, hygiene, childcare, stress management and counselling. Knowledge of traditional healthcare methods, particularly herbal remedies, was in danger of being lost, and a research programme gathered and documented information from the Indigenous tribes to encourage villagers to use them again. Women’s self-help groups were founded to give training in the growing of these herbs to use in primary health care – essential in situations when it could take more than an hour to get to a doctor or hospital from their villages over tortuous, pot-holed roads. Thanks to outside volunteer practitioner therapists, villagers have been able to experience therapies such as cranio-sacral therapy and reflexology, and have started training as practitioners – one good example of how Indigenous peoples can adopt new roles within the context of their own culture and customs, which will be preserved as a consequence.

I SPENT MOST of my two weeks with Vanya discovering my own artistic voice within this region. I travelled in all directions, sometimes alone and sometimes with her. The physical landscape is full of evocatively shaped hills, which continually change as they are circumnavigated. These hills are sacred peaks and comprise an ancient trellis of energy points well known by all the five Indigenous tribes, who appropriate them according to their own traditions. Of these tribes the Toda were perhaps the oldest inhabitants – a people of great dignity who wandered across the grasslands with their sacred buffalo. The Badaga were cultivators and are generally thought to have migrated or been driven up the hills from Karnataka. The Kota were blacksmiths and musicians: their beautiful dances restored and regenerated the Earth each spring. The Irula and Kurumbar were the magicians and sustainers of rituals important to all other groups. These tribes are fast losing their culture, their identities and their habitats. Therefore the work of people like Vanya is of great importance.

There is something very special about Vanya’s methods. It is as though she were a conduit: a transmitter of energy and life which continues the eternal cycle, encompassing the whole of the Earth and our role within it, the cosmos and our awareness of astronomical and astrological forces, and finally our own spirit within, all of which evolve as a result of our interaction within any part of the cycle. There is a profound belief that the ultimate union with God is something which embraces all cultures, races and religions and that the destiny of each one of us depends on the other. Spending time with Vanya immersed me in the fundamental life questions, and gave me a new respect for the Earth and her people that I had previously misunderstood. I intend to return to the Nilgiris again, to finish my art projects and bring to the exhibition space a sense of place extraordinary.

For more information contact Vanya Orr at [email protected]