Subversive, witty, cultish, street-wise, satirical, activist: these among others are words that seek to define the artist called Banksy. He delights in denying descriptions of himself just as he ducks attempts at establishing his identity. What is undeniable is that he has created a cultural chemistry that has engaged the public: up to 6,000 people each day queued for three hours or more to get into his exhibition in the Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery, this summer.

His audience ranged from parents with infants to people well into their senior years; local residents coming to celebrate this ‘son of their city’, and those magnetised from afar by his mythology. There were whole family groups whose teenagers are normally disengaged as they obsessively text friends, but in this enormous queue teenage eyes were engaged as they chatted with their neighbours in the line. They were there sharing a common curiosity. This was a museum queue like no other: waiting to see the work of a graffiti artist lauded by critics and exhibiting work in a place where not so long ago he would have smuggled it in and placed it on illicit display.

Banksy was probably relishing it all. But was this exhibition compromising the principles of street art? It was certainly a long way from the sharp ‘stencil art’ made by the lone urban guerrilla graffiti artist he once was, giving rise to the question of whether his ‘anonymity’ is merely part of a deliberate stance to enhance the mystery.

It would be all too easy to romanticise Banksy’s work. I think he has been both lucky and canny. Because his stencilled images usually first appear on the street, people are attracted to his daring, to his illegal interventions and to his evident dark humour. He is working during a period when the public in general feel alienated from elected representatives and discontented with many aspects of the establishment. Banksy has sparked the traces of their dissidence. He provokes smiles at a bleak time.

Banksy originally seemed to be challenging the conventions of the art world, but the editions of spray-painted stencilled canvases, the approval of Damien Hirst, who has collected his work, and the scramble by the ‘fashionable set’ to scoop it up point more and more to Banksy’s acceptance of some aspects of these conventions. If Banksy is to hold on to the radical ground he once commanded, he needs to keep undertaking risky interventions on our streets.

The street-art movement is well over thirty years old; indeed, forms of graffiti can be found as drawings and writing from Roman times onwards. In 1979 John Fekner stencilled the Pulaski Bridge in New York City with the slogan ‘Wheels Over Indian Trails’, making an acute reference to the marginalised and dispossessed Indigenous people. London saw the Free George Davis campaign use painted slogans in the same decade to huge effect as tall buildings were scaled to bring injustice to notice. In Paris Blek le Rat continues to stencil consciousness-raising images on the streets, as he has done since 1981.

Banksy is quick to acknowledge Blek le Rat’s influence, but his own ambitions have moved him towards the mainstream. There is a sense that the co-operation with galleries, the prints, the merchandise and the move to humorous gallery installations are a distraction. Something about the idea of the sale of ‘street art’ and the evidence of a productive and protective organisation around Banksy is unsettling.

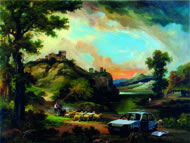

The Bristol show was called Banksy versus Bristol Museum – but there was no evidence of struggle. This was Banksy in the museum with all their help and co-operation. Paintings by ‘A Local Artist’ were substituted in rows of conventional rural landscapes, and the ‘Local Artist’ had added burnt-out cars to rather badly painted pastiche landscapes. Other well-known works were wittily ‘adjusted’ but the inclination was for sensation rather than subtlety. Unarguably visitors were drawn to look at other works as they engaged in the game of ‘hunt the Banksy’ but I was left feeling that many of his offerings were a bit light-weight.

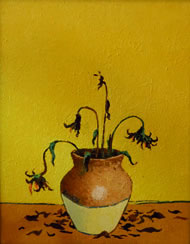

Caged models of animals delighted children and some adults. A hen watched as her chicken-nugget chicks pecked at a dish; witty at best but hardly something to make a complex sculpture about. Similarly, a leopard-skin coat wagged its tail from its perch on a branch. They left no mystery, raised no really new issues, and work on a single level. It felt like entertainment, even if it was of a waspish kind.

In the aisles of the ground floor, casts of famous statues had been replaced by altered works. Michelangelo’s David had become a suicide bomber, and others had been turned into a compulsive shopper and a bag lady. There were acute reminders of the widening gap between the rich and the poor. It is in such works that Banksy seems to be most effective. We are needled into a state of alertness, of shame even.

The ironic, idyllic paintings of beach play on the segregation wall in Palestine, like the edgiest work Banksy has made in cities, seem to me to be the strongest work. If we are moved when confronted by our unconscious acceptance of malevolent change, whether it is the bullish tactics of the Israelis or the slide to a surveillance society in Britain, then Banksy has succeeded. If part of what art can do is to make us consider the world differently, then these works are powerful in that sense.

It could be argued that the humour of other works might lead his fans to the more serious imagery but I think they lead to dilution. The vast pink ‘BORING’ sprayed by fire extinguisher over one of the blank façades of the Southbank Centre by the Thames in London is pretty much as dull as Banksy gets. It’s a modernist building that gained that kind of comment from its inception, so apart from reflecting a popular view, the act of doing it is itself a bit of a yawn.

Banksy has caught the public mood. People are delighted by his gift of a major exhibition to the city of Bristol. In his best work he stirs things up, unsettles us and exposes. But he has become an organisation, and the danger of that is in the risk of losing a sense of clarity and the edge of radical quality.