My five-year-old daughter Mini can’t stop talking for a minute. It only took her a year to learn to speak, after coming into the world, and ever since she has not wasted a minute of her waking hours by keeping silent. Her mother often scolds her and makes her shut up, but I can’t do that. When Mini is quiet, it is so unnatural that I cannot bear it. So she’s rather keen on chatting to me.

One morning, as I was starting the seventeenth chapter of my novel, Mini came up to me and said, “Father, Ramdoyal the gatekeeper calls a crow a kauyā instead of a kāk. He doesn’t know anything, does he!”

Before I had a chance to enlighten her about the multiplicity of languages in the world, she brought up another subject. “Guess what, Father, Bhola says it rains when an elephant in the sky squirts water through its trunk. What nonsense he talks! On and on, all day.”

Without waiting for my opinion on this matter either, she suddenly asked, “Father, what relation is Mother to you?”

“Good question,” I said to myself, but to Mini I said, “Run off and play with Bhola. I’ve got work to do.”

But then she sat down near my feet beside my writing-table, and, slapping her knees, began to recite ‘āgḍum bāgḍum’ at top speed. Meanwhile, in my seventeenth chapter, Pratap Singh was leaping under cover of night from his high prison window into the river below, with Kanchanmala in his arms.

My study looks out onto the road. Mini suddenly abandoned the ‘āgḍum bāgḍum’ game, ran over to the window and shouted “Kabuliwallah, Kabuliwallah!”

Dressed in dirty baggy clothes, pugree on his head, bag hanging from his shoulder, and with three or four boxes of grapes in his hands, a tall Kabuliwallah was ambling along the road. It was hard to say exactly what thoughts the sight of him had put into my beloved daughter’s mind, but she began to shout and shriek at him. That swinging bag spells trouble, I thought: my seventeenth chapter won’t get finished today. But just as the Kabuliwallah, attracted by Mini’s yells, looked towards us with a smile and started to approach our house, Mini gasped and ran into the inner rooms, disappearing from view. She had a blind conviction that if one looked inside that swinging bag one would find three or four live children like her.

Meanwhile the Kabuliwallah came up to the window and smilingly salaamed. I decided that although the plight of Pratap Singh and Kanchanmala was extremely critical, it would be churlish not to invite the fellow inside and buy something from him.

I bought something. Then I chatted to him for a bit. We talked about Abdur Rahman’s efforts to preserve the integrity of Afghanistan against the Russians and the British. When he got up to leave, he asked, “Babu, where did your little girl go?”

To dispel her groundless fears, I called Mini to come out. She clung to me and looked suspiciously at the Kabuliwallah and his bag. The Kabuliwallah took some raisins and apricots out and offered them to her, but she would not take them, and clung to my knees with double suspicion. Thus passed her first meeting with Kabuliwallah.

A few days later when for some reason I was on my way out of the house one morning, I saw my daughter sitting on a bench in front of the door, nattering unrestrainedly; and the Kabuliwallah was sitting at her feet listening – grinning broadly, and from time to time making comments in his hybrid sort of Bengali. In all her five years of life, Mini had never found so patient a listener, apart from her father. I also saw that the fold of her little sari was crammed with raisins and nuts. I said to the Kabuliwallah, “Why have you given all these? Don’t give her any more.” I then took a half-rupee out of my pocket and gave it to him. He unhesitatingly took the coin and put it in his bag.

When I returned home, I found that this half-rupee had caused a full-scale row. Mini’s mother was holding up a round shining object and saying crossly to Mini, “Where did you get this half-rupee from?”

“The Kabuliwallah gave it to me,” said Mini.

“Why did you take it from the Kabuliwallah?” said her mother.

“I didn’t ask for it,” said Mini tearfully, “He gave it to me himself.”

I rescued Mini from her mother’s wrath. and took her outside. I learnt that this was not just the second time that Mini and the Kabuliwallah had met: he had been coming nearly every day and by bribing her eager little heart with pistachio nuts, had quite won her over. I found they now had certain fixed jokes and routines: for example as soon as Mini saw Rahamat, she giggled and asked, “Kabuliwallah, O Kabuliwallah, what have you got in your bag?” Rahamat would laugh back and say – giving the word a peculiar nasal twang – “An elephant.” The notion of an elephant in his bag was the source of immense hilarity; it might not be a very subtle joke, but they both seemed to find it very funny and it gave me pleasure to see, on an autumn morning, a young child and a grown man laughing so heartily.

They had a couple of other jokes. Rahamat would say to Mini, “Little one, don’t ever go off to your śvaśur-bāṛi.” Most Bengali girls grow up hearing frequent references to their śvaśur-bāṛi, but my wife and I are rather progressive people and we don’t keep talking to our young daughter about her future marriage. She therefore couldn’t clearly understand what Rahamat meant; yet to remain silent and give no reply was wholly against her nature, so she would turn the idea around and say, “Are you going to your śvaśur-bāṛi?” Shaking his huge fist at an imaginary father-in-law Rahamat said, “I’ll settle him!” Mini laughed merrily as she imagined the fate awaiting this unknown creature called a śvaśur.

It was perfect autumn weather. In ancient times, kings used to set out on their world-conquests in autumn. I have never been away from Calcutta; precisely because of that, my mind roves all over the world. I seem to be condemned to my house, but I constantly yearn for the world outside. If I hear the name of a foreign land, at once my heart races towards it; if I see a foreigner, at once an image of a cottage on some far bank or wooded mountainside forms in my mind, and I think of the free and pleasant life I would lead there. At the same time, I am such a rooted sort of individual that whenever I have to leave my familiar spot I practically collapse. So a morning spent sitting at my table in my little study, chatting with this Kabuliwallah, was quite enough wandering for me. High, scorched, blood-coloured forbidding mountains on either side of a narrow desert path; laden camels passing, turbaned merchants and wayfarers, some on camels, some walking, some with spears in their hands, some with old-fashioned flintlock guns: my friend would talk of his native land in his booming, broken Bengali, and a mental picture of it would pass before my eyes.

Mini’s mother is very easily alarmed. The slightest noise in the street makes her think that all the world’s drunkards are charging straight at our house. She cannot dispel from her mind – despite her experience of life (which isn’t great) – the apprehension that the world is overrun with thieves, bandits, drunkards, snakes, tigers, malaria, caterpillars, cockroaches and white-skinned maurauders. She was not too happy about Rahamat the Kabuliwallah. She repeatedly told me to keep a close eye on him. If I tried to laugh off her suspicions, she would launch into a succession of questions: “So do people’s children never go missing? And is there no slavery in Afghanistan? Is it completely impossible for a huge Afghan to kidnap a little child?” I had to admit that it was not impossible, but I found it hard to believe. People are suggestible to varying degrees; this was why my wife remained so edgy. But I still saw nothing wrong in letting Rahamat come to our house.

Every year, about the middle of the month of Māgh, Rahamat went home. He was always very busy before he left, collecting money owed to him. He had to go from house to house; but he still made time to visit Mini. To see them together, one might well suppose they were plotting something. If he couldn’t come in the morning he would come in the evening; to see his lanky figure in a corner of the darkened house, with his baggy pyjamas hanging loosely around him, was indeed a little frightening. But my heart would light up as Mini ran to meet him, smiling and calling, “O Kabuliwallah, Kabuliwallah,” and the usual innocent jokes passed between the two friends, unequal in age though they were.

One morning, I was sitting in my little study correcting proof-sheets. The last days of winter had been very cold, shiveringly so. The morning sun was shining through the window onto my feet below my table and this touch of warmth was very pleasant. It must have been about eight o’clock – early-morning walkers, swathed in scarves, had mostly finished their dawn stroll and had returned to their homes. It was then that there was a sudden commotion in the street.

I looked out and saw our Rahamat in handcuffs, being marched along by two policemen, and behind him a crowd of curious boys. Rahamat’s clothes were blood-stained, and one of the policemen was holding a blood-soaked knife. I went outside and stopped him, asking what was up. I heard partly from him and partly from Rahamat himself that a neighbour of ours had owed Rahamat something for a Rampuri chadar; he had tried to lie his way out of the debt, and in the ensuing brawl Rahamat had stabbed him.

Rahamat was mouthing various unrepeatable curses against the lying debtor, when Mini ran out of the house calling, “Kabuliwallah, O Kabuliwallah.” For a moment Rahamat’s face lit up with pleasure. He had no bag over his shoulder today, so they couldn’t have their usual discussion about it. Mini came straight out with her

“Are you going to your śvaśur-bāṛi?”

“Yes, I’m going there now,” said Rahamat with a smile.

But when he saw that his reply had failed to amuse Mini, he brandished his handcuffed fists and said, “I would have killed my śvaśur, but how can I with these on?”

Rahamat was convicted of assault and sent to prison for several years. He virtually faded from our minds. Living at home, carrying on day by day with our routine tasks, we gave no thought to how a free-spirited mountain-dweller was passing his years behind prison walls. As for the fickle Mini, even her father would have to admit that her behaviour was not very praiseworthy. She swiftly forgot her old friend. At first, Nabi the groom replaced him in her affections; later, as she grew up, girls rather than little boys became her favourite companions. She even stopped coming to her father’s study. And I, in a sense, dropped her.

Several years went by. It was autumn again. Mini’s marriage had been decided, and the wedding was fixed for the puja-holiday. Our pride and joy would soon, like Durga going to Mount Kailas, darken her parents’ house by moving to her husband’s.

It was a most beautiful morning. Sunlight, washed clean by monsoon rains, seemed to shine with the purity of smelted gold. Its radiance lent an extraordinary grace to Calcutta’s back streets, with their squalid, tumbledown, cheek-by-jowl dwellings. The sānāi started to play in our house when night was scarcely over. Its wailing vibrations seemed to rise from deep within my ribcage. Its sad Bhairavi raga joined forces with the autumn sunshine in spreading through the world the grief of my imminent separation. Today my Mini would be married.

From dawn on, there was uproar, endless coming and going. A canopy was being erected in the yard of the house, by binding bamboo poles together; chandeliers tinkled as they were hung in the rooms and verandahs; there was constant loud talk.

I was sitting in my study doing accounts, when Rahamat suddenly appeared and salaamed before me. At first, I didn’t recognise him. He had no bag; he had lost his long hair; his former vigour had gone. But when he smiled, I recognised him.

“How are you, Rahamat?” I said. “When did you come?”

“I was let out of prison yesterday evening,” he replied.

His words startled me. I had never confronted a would-be murderer before; I shrank back at the sight of him. I began to feel that on this auspicious morning it would be better to have the man out of the way. “We’ve got something on in our house today,” I said. “I’m rather busy. Please go now.”

He was ready to go at once but just as he reached the door he hesitated a little and said, “Can’t I see your little girl for a moment?”

It seemed he thought that Mini was still just as she was when he had known her: that she would come running as before, calling “Kabuliwallah, O Kabuliwallah!”; that their old merry banter would resume. He had even brought (remembering their old friendship) a box of grapes and a few nuts and raisins wrapped in paper – extracted, no doubt, from some Afghan friend of his, having no bag of his own now.

“There’s something on in the house today,” I said. “You can’t see anyone.”

He looked rather crestfallen. He stood silently for a moment longer, casting a solemn glance at me; then, saying, “Babu salaam”, he walked towards the door. I felt a sudden pang. I thought of calling him back, but then I saw that he himself was returning.

“I brought this box of grapes and these nuts and raisins for the little one,” he said. “Please give them to her.” Taking them from him, I was about to pay him for them when he suddenly clasped my arm and said, “Please, don’t give me any money – I shall always be grateful, Babu. Just as you have a daughter, so do I have one, in my own country. It is with her in mind that I came with a few raisins for your daughter: I didn’t come to trade with you.”

Then he put a hand inside his big loose shirt and took out from somewhere close to his heart a crumpled piece of paper. Unfolding it very carefully, he spread it out on my table. There was a small handprint on the paper: not a photograph, not a painting – the hand had been rubbed with some soot and pressed down onto the paper. Every year, Rahamat carried this memento of his daughter in his breast pocket when he came to sell raisins in Calcutta’s streets: as if the touch of that soft, small childish hand brought solace to his huge, homesick breast. My eyes swam at the sight of it. I forgot then that he was an Afghan raisin-seller and I was a Bengali Babu. I understood then that he was as I am, that he was a father, just as I am a father. The handprint of his little mountain-dwelling Parvati reminded me of my own Mini.

At once, I sent for her from the inner part of the house. Objections came back: I refused to listen to them. Mini, dressed as a bride – sandal-paste pattern on her brow, red silk sari – came timidly into the room and stood close by me.

The Kabuliwallah was confused at first when he saw her: he couldn’t bring himself to utter his old greeting. But at last he smiled and said, “Little one, are you going to your śvaśur-bāṛi?”

Mini now knew the meaning of śvaśur-bāṛi; she couldn’t reply as before – she blushed at Rahamat’s question and looked away. I recalled the day when Mini and the Kabuliwallah had first met. My heart ached.

Mini left the room, and Rahamat, sighing deeply, sat down on the floor. He suddenly understood clearly that his own daughter would have grown up too since he last saw her, and with her too he would have to become re-acquainted: he would not find her exactly as she was before. Who knew what had happened to her these eight years? In the cool autumn morning sunshine sānāi went on playing, and Rahamat sat in a Calcutta lane and pictured to himself the barren mountains of Afghanistan.

I took out a banknote and gave it to him. “Rahamat,” I said, “Go back to your homeland and your daughter; by your blessed reunion Mini will be blessed.”

By giving him this money, I had to trim certain items from the wedding festivities. I wasn’t able to afford the electric illuminations I had planned, nor did the trumpet-and-drum band come. The womenfolk were very displeased at this; but for me, the ceremony was lit by a kinder, more gracious light.

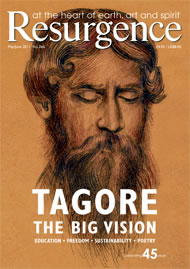

Kabuliwallah is one of 30 short stories written by Tagore and translated by William Radice for the Penguin Classic Rabindranath Tagore. ISBN: 9780140449839