“We must be patient. This stage of the revolution will not be over in eighteen days,” a young woman in Tahrir Square tells a small group. Her nostrils are clogged with tissue to soak up the blood from a nosebleed caused by inhaling tear gas some days earlier. “However, once a nation decides to live, destiny has no choice other than to oblige,” she concludes. But as the situation in Egypt demonstrates, destiny’s path is not always a straight one.

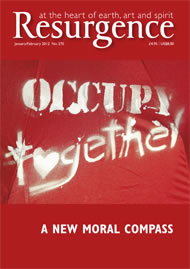

I am in Tahrir Square during the run-up to the first stage of Egypt’s first post-Mubarak parliamentary elections. It is Friday, and five days of violence between the military and protesters have come to an end following an order to soldiers to stop any attempts to clear the square. Tahrir has not witnessed such a crowd since February, and the mood is buoyant. Flags wave and rhythmic chanting echoes off the buildings. At lunchtime, in an unprecedented move, the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar, Sunni Islam’s highest authority, arrives in the square to lead tens of thousands in Friday prayer. Later that afternoon a breakaway group of around a hundred protesters walks the 500 metres to the Parliament and Cabinet buildings and occupies the street that runs between the two. By evening their number has swelled and a handful of soldiers looks on as they set up tents, lay out blankets and begin spraying stencilled graffiti onto the white walls outside Parliament.

Back in Tahrir the crowd remains large but the mood has become more tense. There is talk of “thugs” mingling with the crowd, harassing people, robbing and starting fights. I leave the square after midnight, only to return the next morning to the news that one of the protesters I was with the previous night at the occupation outside Parliament – 19-year-old Ahmed Surur – has been killed, crushed beneath the wheels of a Ministry of Interior armoured personnel carrier. His death follows that over 40 others across Egypt who died at the hands of the security forces over the course of that week. Protesters originally came out onto the streets to oppose proposed constitutional amendments by the military-led transitional government (the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, or SCAF) that would limit the authority of future governments over the army. They were also expressing anger at SCAF’s slow timetable for implementing civilian rule and its blatant lack of respect for human rights over the previous nine months.

The clashes succeeded in persuading SCAF to make some limited concessions. Essam Sharaf’s unpopular civilian cabinet resigned, and a new prime minister, Kamel Ganzoury, was appointed and charged with forming a so-called national salvation government. The date for presidential elections was shifted from early 2013 to June 2012. But, for the protesters in Tahrir Square, this fell far short of their demand for an end to military rule. “Ganzoury is a puppet and I don’t trust SCAF to hand over power,” political activist Salma Hegazy told me. “They will use these elections to give the impression of backing democracy whilst doing everything they can keep the influence and privileges.”

Although there were calls from some quarters for an electoral boycott, the high turn-out at the polls suggests that most Egyptians hoped that elections will at least take the country closer to the establishment of a civilian government. During the elections the crowd in Tahrir Square was much smaller than it had been on preceding days, but there were still groups chanting and flags waving as well as clusters of people engaged in heated debate. One of the main discussions amongst activists in Tahrir centred on whether voting would lend legitimacy to an election that, no matter the result, will see SCAF retaining ultimate power. Other groups in Tahrir Square discussed the merits and composition of the proposed government of national salvation and the way forward for the Tahrir-appointed civil presidential council chaired by Abdel Fotouh, Mohamed ElBaradei and Hossam Essa.

Feelings ran high, but despite differences of opinion all agreed that military rule must end and most agreed that the Tahrir Square occupation should continue until it does. “To dismantle our tents before then would be to dismantle our hopes for a better future,” Mourad Haikal told me. “Whatever happens in the elections the important thing is that Tahrir should stay.”

As polling stations closed their doors on Tuesday night the mood in Cairo was far from celebratory. Despite a high turnout (62%) and widespread relief that the two days of voting had not been marred by violence, the elections had left many far from satisfied. Beyond the concerns at voting irregularities and overly complicated ballot papers, many felt that the election process – due to go on for another three months – lacks legitimacy.

The results, released the following Sunday, show that Islamic parties took a total of 65% of the vote, pushing the coalition of liberal parties into third place. Whilst the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party (FJP) performed as expected, winning the largest share of votes, with 36.6%, it was the 24.4% of votes won by the ultra-conservative Salafist Al-Nour Party that caused the greatest surprise. Whilst the FJP advocate the application of some aspects of Sharia law, they have made efforts to position themselves as a moderate, democratic and inclusive party. The Salafists, by contrast, take a more hard-line approach, rejecting the very concept of democracy, which they believe allows man-made law to take ascendance over God’s law. “The extremist Islamic parties would attempt to kill democracy by democracy,” political analyst Ahmed Abdel Maksood tells me. “If they were to win a parliamentary majority they would amend the constitution and bring in an Islamic state.”

Maksood is nevertheless optimistic about Egypt’s future. Last month’s return to Tahrir Square not only succeeded in reawakening the spirit of defiance in Egypt and achieving some significant political gains, but also cemented the position of Tahrir Square as a permanent practical and symbolic heart of the freedom movement in Egypt: a place to which people can always return and whose very existence will help shape Egyptian politics for generations to come. As Maksood puts it, “The January revolution gave us the path. It showed us the way. We now have a weapon and that weapon is called Tahrir Square.”

Before I leave Cairo I go to Tahrir Square for a final time. The tents are still there but the crowds have dwindled significantly. Many of the traders, including the gas-mask sellers, have moved on. The field hospital is still there beside the mosque, and next to the hospital an ambulance is taking blood donations. I fill in a form, have my haemoglobin tested and then climb into the ambulance to give some blood. “Hopefully you won’t need it,” I joke to the young doctor as he inserts a needle into my vein. “Oh, we will need it,” he replies earnestly. “I fear there will be a need for much blood in Egypt for months and years to come.”