TG: Garry, I think it must be nearly twenty-five years since our first meeting?

GFM: Almost, it was 1987 when I was invited to participate in the Artists’ Parish Maps exhibition organised by the arts and conservation group Common Ground. My memory is that we met at Meavy, and that you’d organised a day to explore a little of Dartmoor. What can you remember about that?

TG: I remember particularly our visit to Wistman’s Wood.

GFM: I remember going there, that photo that you took of me in Wistman’s Wood is the thing that really brings it back. It was high summer and I am sitting in the wood reading Ruskin’s Frondes Agrestes. Then I was involved in a kind of nature-worship, encouraged by Chris Titterington, the curator of photographs at the Victoria and Albert Museum. He had discovered my work around this time and was excited about its use of photographic materials and plants, and the way it related to the romantic tradition of artists working with nature. I do remember on that first visit you taking me to Holne Moor, and walking from the reservoir to a large tor. You pointed out the reaves going across Holne Moor appearing to ignore the deep gorge of the river Dart. I remember walking and not seeing it – then seeing it – and you discussed with me what the reaves were. This was the mid-1980s when the reaves were a new and exciting archaeological ‘moment’…?

TG: Absolutely, and they’re still new in terms of archaeology! A reave is a prehistoric land boundary dating back to the mid-second millennium. Research since the 1970s revolutionised our understanding, not only of Dartmoor but also of prehistoric Europe, and this still reverberates across the archaeological world.

GFM: It made me think of a whole genre of artwork that had come out of the 1960s, which went under a heading of ‘land art’. Here people were going into the landscape and engaging with it in a physical sense, often on a large scale. In England the best-known example would be Richard Long. In America a different approach developed on a much more heroic scale; you had artists making huge earthworks in desert landscapes, in contrast to the more domestic English manifestations of artists like Richard Long and Hamish Fulton.

GFM: Before this day my first memories of Dartmoor were as a child being taken on a holiday in the sixties, probably around 1964. I remember being in the car being driven across Dartmoor with my family travelling to Cornwall. I recall Dartmoor being described as a dangerous place in stories by my father. You were born almost here, so what were your first memories of being taken up onto the moor as a child?

TG: Well I was born in Plymouth and at the age of seven we as a family moved out to Yelverton, which is on the west side of Dartmoor. Our house had a view right across to the western flank of Dartmoor, so I was constantly impressed by this wonderful range of hills extending all the way from Cox Tor to Shell Top, that whole western flank. And that was imprinted on my mind wherever I went, I suppose. A lot of what I have learnt about Dartmoor actually comes from people who are much more deeply part of the place than myself, people whose families have lived there in some cases for many generations.

GFM: I feel part of this human layering, of lives lived, traces left, from the repeated walks and unfolding series of pictures that I make. I return to the same places. I have perhaps 6-10 walks that I repeat 3 or 4 times each month. For example in December, the sun rises at 8.20am and this coincides with low night temperatures, ice and frost. The low raking light strikes an object on the land’s silvered surface, and throws a shadow line revealing things which have lain hidden for 6 months or more, and you see anew.

On days such as these I have seen both the Spectre of the Brocken and a parhelion when walking on Hamel Down. This connects to our early conversation about Ruskin and the Romantic Movement. Coleridge and others would go on walking tours in Germany to the Harz mountains seeking a glimpse of the conjunction between clouds, sky and shadows that brings forward a figure across the cloud floor. Or, more often, the parhelion or a spectral double sun. Experiences such as these change your world and greatly influence the pictures I make.

Stephan Graham writes in his book The Gentle Art of Tramping (1923) “As you sit beside a hillside, or lie prone under the trees of the forest, or sprawl wet-legged by a mountain stream, the great door, that does not look like a door, opens.” I believe in this opening of a golden door. I made a cycle of pictures (Year Two, 2008) each lasting one-month, a lunar cycle, and each series named after minerals found in the ground I walked upon. In the last series, Lead, this idea of experiencing the opening door was imagined.

TG: But I think that’s exactly my experience, in a way, as well – that I’m looking out for things to happen, to come across something which I haven’t noticed before – it might be because of the particular weather conditions or the light conditions. And my expectation when walking is that there’s always the possibility of new things being revealed in whatever sense.

GFM: One thing that I’m interested in particularly, Tom: the day you were walking and made one of your more recent discoveries, the Cut Hill stone row.

TG: Cut Hill is a very massive, rounded hill with no significant rock outcrop on it, right in the heart of northern Dartmoor, towards the head of the River Dart, or the East Dart river, and also the river Tavy has its head waters just to the south of Cut Hill. And so it’s a very dominant hill, almost 2000 feet high, or 600m, and a very remote spot. Right on the very highest point I noticed this discrete mound and I thought to myself, ‘Well, that looks like a prehistoric barrow, a burial place’. I then moved a short distance north-eastwards from there, still standing on the deep peat, and looked across a 100 yard stretch of ground where the peat had been dug away or eroded, and, looking in that north-easterly direction, I suddenly saw five large slabs of granite all laid out flat on the ground, but all with the same orientation and all evenly spaced. Almost instantly I recognised them as being artificially placed and that the only reasonable explanation for them was that they were part of a prehistoric stone row, but that the stones had fallen over.

Since that discovery there’s been some very interesting work done there, mostly by Dr Ralph Fyfe of Plymouth University who’s been able to analyse the peat and date the stone row very precisely to the mid-4th millennium BC. So the likelihood is that the stones were set up around 3500 BC or possibly earlier, but that by 3300 BC they had fallen over, having been deliberately placed on the ground. Within 900 years, by 2400 BC, those stones had been covered with peat, and so were invisible in the landscape by then. So that’s the essence of Cut Hill – we now know of nine stones and a total distance for the row of over 200m in length, but we haven’t confirmed either end of it yet.

Some of the most enduring prehistoric artefacts found on Dartmoor are tools and arrowheads made of flint, which does not occur naturally on granitic Dartmoor and all of which must have been brought to the moor. The greatest known concentration of flints within the Dartmoor area comes from farmland close to Whiddon Down, on the north-eastern edge of the moor. The many thousands of flints from here were found in the mid-twentieth century by Capt. Oscar Greig who lived at Throwleigh. This remarkable collection is now stored at Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter.

GFM: On this occasion I am very pleased that an opportunity has arisen for me to exhibit my work in the South West of England for the fine new galleries at the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter. I’ve chosen a group of seven large circular pieces. One group came from a period when I decided to spend a lot of time walking at night. It is probably the time that when I am on the moor I feel most out of any time period. I feel as if I could be walking today or I could be walking several thousand years ago. The night walking also connects to the place in which the pictures are made, the dark room. I’m interested that I’ve chosen to make a form of art where the making takes place somewhere like a cave. Somewhere you illuminate - it’s a primitive, simple place in which I’m using quite contemporary scientific tools to make images visible.

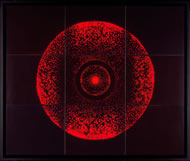

The other circular works connect to an opposite place. I’ve increasingly begun to seek a sense of what lies beneath the ground. A picture like Exposure in the exhibition, a large circle made of radiating points of red light coming from a central red circle, is trying to bring forward a hot radiating energy which constantly burns in the earth’s inner darkness. When I’ve chosen to make pictures in recent years I’ve given them the names of minerals which are in the ground which I’m either walking on, or that lie close to the ground I’m walking on – things found on Dartmoor like arsenic, tourmaline, lead.

The final group of pictures in the exhibition also refers to the circularity of our lives. My relationship with Royal Albert Memorial Museum began with exhibitions that featured my plant-based practice, a period of work that broadly ended in the early 1990s. Unexpectedly this spring, I re-engaged with this method of work. I think this was prompted by the beauty of recent springs and many days spent looking at and into blossom trees. The solitary hawthorns on the high moor, the hedges of hawthorns and blackthorn, and the apple trees in our orchard. This prompted me to reconsider the early plant pictures and how, to me, those simple common plants somehow seem to contain great meaning as they emerge.

Dartmoor has become my home and for me, much of its meaning is contained in the lives of the people that have lived, worked and walked here before me. As I pass through the footprints of hut circles I often linger and reflect on the people that looked out from the doorway and our shared relationship to the seasons, weather and forces that surround us. The sky space soaring above us, the skylark, the wonder of the emerging ash buds, all suggest we are in the right place and at the right time. It’s a good place to be Tom…

TG: I couldn’t agree more. The present must be the most interesting period for any human being. The more people engage with ideas and decision-making, the more chance there is that we will establish a sensitive, thoughtful and caring society on Dartmoor. With new vocabularies, such as your own artwork, we can begin to articulate the felt significance of such cultural depth, which hopefully will help lead to a renaissance in how people treat, and relate to, Dartmoor.