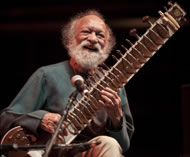

Ravi Shankar, the great Indian sitarist, was one of the most influential of musicians. He inspired people from all walks of life, and musicians from all genres of music. These included such names as George Harrison, Yehudi Menuhin, John Coltrane and Philip Glass. Ravi Shankar’s music rapidly spread throughout the world, crossing all cultural and generational boundaries.

I had the great privilege to work on many projects with Ravi from 2004 until his death in December 2012. These projects included the world première of his Symphony with the London Philharmonic Orchestra at London’s Royal Festival Hall, with his daughter Anoushka as soloist.

I will never forget the sessions with Ravi preparing his new works. His composition process, like Beethoven’s in the Western classical world, involved going into a creative ‘raptus’, and from this his ideas would flow. I would put these ideas down on paper and then work with Ravi to realise them for Western instruments, Indian instruments and voices. Computer technology was ideal for this process. Over the years I was working with him, technology developed so that the computer simulation of instrumental sounds became far more accurate (although the computer’s attempt to sound like a sitar always amused him!). This meant that we could experiment: I could prepare different orchestrations and harmonisations of his ideas, and we would refine them until we had reached his ideal sound.

Ravi Shankar’s final artistic vision was to create the world’s first East–West opera, joyfully uniting the music of both hemispheres in an entertaining, uplifting work that also communicates the elements of Indian spirituality that were so important to him. Our focus turned to this in 2010, immediately after the première of his Symphony. The opera, entitled Sukanya, will unite the power of music, sound and vision in a groundbreaking combination.

I am currently completing the work from Ravi’s notes and sketches and with input from his daughter Anoushka and his widow, Sukanya Shankar.

Ideas for Sukanya had been germinating in Ravi’s mind since 1995 and reached a peak from 2010 onwards. Knowing that at the age of 90 his time was limited, he worked incredibly quickly, his musical mind gushing streams of creative ideas. He had a vision for the work that would break the mould of traditional opera: a truly groundbreaking creation that would explore the common ground between the music, dance and theatrical traditions of India and of the West. To fulfil this vision Ravi envisaged the opera scored for Indian and Western musicians, Indian and Western voices, and Indian dancers. He was fascinated by film and visual imagery, and envisaged the visual elements of Sukanya enhanced by electronic projection.

Sukanya is based on a story from the Mahabharata. The libretto is by the Indian author Amit Chaudhuri. A joyful, accessible piece, it is about the discovery of love late in life. It also relates to Ravi Shankar’s own experience of life and love.

In the story, Chyavana, a young man, is meditating in the forest. His meditation becomes so deep that ants begin to build a nest around him. Many years pass and a huge anthill is formed.

One beautiful spring day King Shryayati comes to the forest with his retinue for a spring festival. His only daughter, Sukanya, notices the anthill, and seeing what look like two jewels glowing from within, she pokes them with a sharp stick.

There is a scream from inside the anthill, the glow goes out, and Sukanya, terrified, runs away. The king investigates the huge anthill. Chyavana, now a great sage and a very old man, is revealed beneath; he has been blinded, and as compensation he asks for Sukanya’s hand in marriage.

The king, aware of Chyavana’s spiritual stature, agrees. Sukanya lives with the sage happily and faithfully in the forest.

One day she is spotted by the Ashwini Devas, two beautiful, youthful, identical twin demigods. They ask: “Why are you with this old man when you could marry one of us and live in paradise?”

Sukanya politely refuses the offer, confirming her devotion to her husband. The young demigods speak again. “We have a deal for you. We will make your husband young and handsome exactly like us. You must then choose one of us three as your partner.” Sukanya decides to take this test.

The youths ask her to bring her husband to a lake. The sage and the young demigods immerse themselves completely in the water at the same time. When they reappear, Sukanya finds three identical handsome youths. There are several different permutations of the story at this point – all will be revealed in the coming world première of the work!

In his last years Ravi Shankar was exploring entirely new musical territory. Sukanya will demonstrate this, containing, for example, Indian spoken percussion – konnakol – with operatic lines in the Western style floating above. This creates a new, absolutely unique sound-world. Sounds such as these encapsulate Ravi’s aim of bringing the music of East and West together so that the sum is greater than the parts.

The essence of the opera can be summed up in Ravi’s own words: “The system of Indian music known as Raga Sangeet can be traced back nearly two thousand years to its origin in the Vedic hymns of the Hindu temples, the fundamental source of all Indian music. Thus, as in Western music, the roots of Indian classical music are religious. To us, music can be a spiritual discipline on the path to self-realisation, for we follow the traditional teaching that sound is God – Nada Brahma. By this process individual consciousness can be elevated to a realm of awareness where the revelation of the true meaning of the universe – its eternal and unchanging essence – can be joyfully experienced. Our ragas are the vehicles by which this essence can be perceived.”

The opera Sukanya launches in May 2017. Full details of the tour will be announced by the Royal Opera House and the London Philharmonic Orchestra at the beginning of 2016. Fore more information: www.ravishankaroperaproject.org