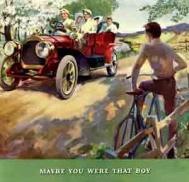

I DON'T DRIVE. But my life is dominated by cars. They are around me and inside me; I breathe their fumes every time I walk along a road. As a child I breathed in their glamour and persuaded my parents to buy me countless toy cars.

The first car our family had even looked like a big toy. It was called a Standard Penant. Disturbingly I can remember its number plate more easily than my family's birthdays. When it was sold I mourned the window stickers from Welsh campsites that I had lovingly put on the passenger side window. Freudians have a term for how people invest emotion into inanimate objects. It's called cathexis. It happens a lot with cars.

Now they are everywhere I look. I dodge between them going from any one place to any other. I shout over them to have a conversation walking down the street. I wake up to their sound systems in the small hours as they park or drive by my house. Places that I love have been divided and paved over to make way for cars. Until a new traffic system was introduced to my home town in Essex I could cross into the town centre by walking over a road of two lanes. After, I had to cross about thirteen lanes.

A car showroom now sits at the corner of that junction. One time I walked past and there were large posters in the window advertising the latest 'retro' model of car produced by the manufacturer Chrysler. As I stood outside, the windows picking up reflections of a bleak landscape - a spaghetti mess of traffic lanes and vulnerable pedestrian islands - the posters nevertheless invited me to "Buy your soul", by purchasing the PT Cruiser. Dr Faust was at work.

Cars cover and suffocate our lives but somehow their dominance is also strangely invisible. Our unique adaptability as a species has enabled us to acclimatise to their staggering 'everywhereness', and not see it as odd. Were the car a disease it would be an epidemic. Yet, spellbound, we embrace the great destroyer and design our lives, communities and countryside around it. We welcome cars into our lives when, rationally, we should be emblazoning them with public health warnings in the same style as cigarette packets. 'Driving can seriously damage your health', or 'Driving Kills'.

In the century since the first recorded fatal traffic accident, the car has claimed thirty million lives. Traffic accidents are now predicted by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies to become the world's third most significant cause of death and disability by 2020. The World Health Organization estimates that 1.2 million people die on roads each year: similar to total fatalities caused by malaria.

Where the unsustainable use of fossil fuels is concerned, nothing is more symbolic than the car. If attitudes towards the car were to change, in much the same way that attitudes towards smoking already have, we might reasonably conclude grounds for hope in the face of the ecological debt of climate change. The opposite is also true.

So deeply is the car built into the organisation of society, the running of the economy and the construction of our own identities, that a change in attitudes towards it might signal public readiness for action on climate change. Action that is finally commensurate with the scale of the problem.

THE CAR HAS not simply stumbled into its current iconic and dominant status. History's biggest red carpet has been rolled out for it. Like a spoilt young prince it was born and brought up with an economic silver spoon in its mouth. Margaret Thatcher, as prime minister when I was growing up, told us we were living in a "great car economy". Roads and car parks were built for it at public expense. Competition, like the railways and trams, had already been deliberately run down in its favour.

In Britain the Beeching Plan, devised by the engineer and chairman of the British Railways Board, Richard Beeching, between 1963 and 1965 paved the way, metaphorically and literally, by shutting down a huge portion of the railway network. His contribution to pulling apart a more environmentally friendly transport system earned him a knighthood.

In the 1920s most significant towns and cities in the United States had their own electric rail systems: the famous streetcar. There were 1,200 separate systems with 44,000 miles of track. The car company General Motors (GM) made a loss in 1921 and feared that the car market had hit a wall. Its answer was to target the street and urban railways with a range of strategies to put them out of business and increase the market for automobiles. A special unit was set up within the company and it was disturbingly successful. Former US Senate Counsel Bradford Snell writes: "GM admitted, in court documents, that by the mid-1950s, its agents had canvassed more than 1,000 electric railways and that, of these, they had motorised ninety per cent."

The good behaviour of the car, like the ability to get you around (if ever more slowly) was fawned over. Bad behaviour, like killing and injuring people on an epidemic scale and trashing both the urban and the rural environment, was indulged and ignored. Thatcher never mentioned what happened when problems hit the great car economy, and now there is malady in our dependence. Comedian and activist Michael Moore first came to prominence with a film called Roger and Me about the impact on his home town of the closure of a car manufacturing plant. The town's economy depended almost entirely on it. Across Britain other towns suffered similar fates as car making became increasingly mechanised and shifted to Asia in the 1980s and 1990s.

But the car's royal protection squad is more active today than ever. And our addiction to an ever more powerful vehicle 'high' is getting stronger. Around fifteen million vehicles are sold in Western Europe every year. The market is not only big but highly concentrated in the hands of a few giant corporate groups. Just six corporations account for seventy per cent of global car sales.

Potential environmental improvements in car design have been rubbed out by the fact that people want bigger, faster and off-road cars. In the US, overall vehicle fuel economy was lower in 2000 than it was in 1980. According to the Union of Concerned Scientists, "Two decades of fuel-saving technologies that could have helped curb CO2 have instead gone into increasing vehicle weight and performance." In Europe advertisers claim a similar trend. Feeding an "active car buying Audience" on the internet, the company Adlink points out that "Europeans like their cars fast! The average power of car engines has increased by twenty-five per cent in the last ten years."

Of course the demand for large fast cars doesn't just happen. Around six billion euros was spent on car advertising in the five biggest European markets in 2000. In the US, advertising spending to keep cars moving through the showrooms was around $10 billion in 2003 and still rising. The money is not just thrown around. Although car makers keep it quiet, careful psychological research goes into every stage of product development from the design of components through to advertising the final product. Each decision is carefully measured to maintain the apparent indispensability of the car to our lives. The process has been quite amazingly successful.

In 1950 there were an estimated seventy million cars, trucks and buses on the world's roads. Towards the end of the century there were between 600 and 700 million. By 2025 the figure is expected to pass one billion. But the distribution of vehicle ownership is, and will continue to be, highly unequal around the world. In the middle of the 1990s, for every 1,000 people in the United States there were 750 motor vehicles. In China, for the equivalent number of people there were eight vehicles; in India, seven. Even by the year 2050 with the expected huge growth of car ownership in the majority world, rich countries with only sixteen per cent of the world population will still account for sixty per cent of global motor vehicle emissions. Our use of, and dependence on, the private motor car is the badge of membership of the ecological debtors' club.

The messages used by the industry exploit our fears with breathtaking hypocrisy, and occupy our dreams like an invading army. They all work to maintain the car in its uniquely privileged and heavily subsidised position.

THE FANATICISM WHICH ushered in the automobile age is illustrated by the tale of Colonel Moore-Brabazon, a man who was to become minister of transport. In 1932 the Colonel dismissed complaints about the rising number of people dying on the roads. "Over 6,000 people commit suicide every year," he said, "and nobody makes a fuss about that." His credentials for ministerial office were clearly impeccable.

Change, and an end to ecological debt, demands that we 'untell' the stories told every day on behalf of the car in a thousand newspaper and magazine adverts. These adverts are, for the car industry, the equivalent in propaganda to Stalin's state propaganda posters, newsreels and artwork of happy smiling workers. They hide a brutal reality and a naked, dissolute emperor.

Adapted from Andrew Simms' new book Ecological Debt: The Health of the Planet and the Wealth of Nations (Pluto Press, 2005).

A new short film studying 4x4 drivers shows the true attitude of drivers of these much vilified vehicles www.conscience-uk.com/poorvehiclechoice.htm