CLIMATE CHANGE is beginning to awaken people to the fact that our species has permanently damaged the planet. In discussions with indigenous elders in Africa and the Amazon, their first question is, what is the source of the crisis now confronting us? The essential truth, which the climate discourse tends to avoid, is the interconnectedness of the symptoms: the sixth mass extinction of species; global warming; depletion of minerals and fossil fuels; escalating social inequity, toxic pollutants in the Earth’s soils, seas and atmosphere; and the globalisation of the Western industrial model of ‘development’ penetrating into the farthest reaches of the planetary ecosystem. It is this industrial paradigm which has generated the symptoms of climate change. It has cultivated a belief that the Earth’s abundant complex living biosphere is nothing more than resources to be exploited.

The industrial paradigm has been so well-articulated over the last 200 years, that the education, health, media, government and corporate sectors each reinforce the belief that progress is about more money and things; that consumption brings wellbeing; that endless economic growth will trickle down to the burgeoning ‘poor’, despite all evidence to the contrary; and that human nature is inevitably greedy and selfish – a necessary belief to drive industrial growth.

Even those challenging this thinking seem often to forget that this is a very new philosophy for humans, and there are a myriad other cultures still resisting the industrial onslaught: cultures in which different aspects of human nature are strengthened and nurtured, such as co-operation, community, and reverence for Nature.

WHEN HAKIM ABEBECH, a traditional healer from an Ethiopian lineage that goes back thousands of years, was asked how she saw the Western industrial process, she said, “It is very young, and from what I see, it will not last because it does not understand or abide by the governing laws of the Earth.”

Ailton Krenak, the charismatic Brazilian indigenous leader, says, “Westernised people behave like teenagers, rebelling against the laws of Mother Earth, taking as much as they can. This cannot go on… eventually they will get sick – physically, emotionally, and spiritually. The Earth is the source of all nourishment. If we destroy her, we destroy ourselves.”

The knowledge of indigenous peoples, accumulated over centuries, has developed sophisticated ways of reading the language of Nature, so that they are able to dialogue with Nature and meet their needs in a mutually enhancing way. Respect for the Earth and for the different ways in which cultures nurture these values in society is at the core of indigenous peoples’ understanding of biodiversity.

Lionel Cerruto, a Bolivian indigenous leader, sees the challenge like this: “The industrial process fragments society and Nature; it then creates bureaucracies to organise the fragments, and human laws to control them. Our challenge is to rebuild communities in which Pachamama [the living Earth] is understood as the primary source of law and order.”

Climate change reflects the consequences of breaking these laws and the disorder created as a result. The disorder is at all levels of the Earth system, including human society itself. Climate change is therefore a symptom of a deeper malaise. Our fragmented thinking, which denies the primacy of the Earth as the source of all life, is now our greatest impediment in meeting the challenge of the moment.

James Lovelock laments this fragmentation even within the Western scientific tradition: “We need to understand the consequences of adding greenhouse gases to the air; but also of removing natural forest… we need to understand the influence of clouds, oceans, and the Earth’s natural ecosystems. Each time we undermine one of these aspects we disable the Earth system’s capacity to regulate itself.”

This is why the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predictions are underestimating the severity of climate change, because they do not factor in the whole system. As Lovelock states, “In our hubris we believe that we can be stewards of the Earth long before we understand it.”

In addition to acknowledging our ‘eco-illiteracy’, the ‘corporate climate coup’ also needs to be recognised if we are to see through the present discourse on climate change. Historian David Noble eloquently documents the various corporate climate initiatives, which “aim to appropriate the issue in order to moderate its political implications, emphasising the primacy of market-based solutions…and diverting attention from the radical global justice movements, which were challenging corporate power.”

THIS ISSUE OF Resurgence aims to question some of the basic assumptions which are holding us to ransom in the dominant climate discussions, and to bring in voices that are seldom heard, from Africa and Brazil amongst others. These visionaries are calling for an integrated approach to climate, biodiversity and livelihoods, to overcome the fragmentation that permeates our minds and our society and, thereby, our capacity to respond.

The great challenge that climate change presents the Western industrial mind is to learn the language of the Earth, so that we can once again live by her immutable laws. For this, we need to find ingenious ways to reconnect with the natural world, her cycles, abundance and intelligence.

Einstein understood this: “A human being is a part of a whole, called by us ‘universe’, a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings as something separated from the rest...a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest to us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of Nature in its beauty.”

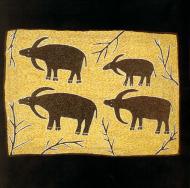

Human societies through the ages have transmitted their ways of knowing life on this planet, through teaching stories, images, rituals, poetry and song. This is the perennial wisdom, which also exists in the Western tradition, where the Earth is understood as the primary source of nourishment and meaning. In order to comprehend the complex living system of which we are an inextricable part, we need to reconnect with the poetic language of the imagination through which we can feel for those other than ourselves and our own species.

There are social and ecological movements around the planet that are building resilience into new natural systems, from the grassroots up. This is where people are simply getting on with Gandhi’s ethic of non-participation in systems of violence, while creating real integrated alternatives to the self-destructive industrial mode of being. Let us join them.