IN PROZAC NATION, the memoir which struck a chord with millions of Americans, Elizabeth Wurtzel wrote, “I don’t want any more of this try, try again stuff. I just want out. I’ve had it. I am so tired. I am twenty and I am already exhausted.” Despite the fact that we are surrounded by labour-saving devices, despite convenience and comfort being elevated above almost every other value, a profound sense of tiredness seems to be one of the defining features of modern life. And our world is as exhausted as we are. Our ecosystems are stretched far beyond their limits, and social structures like families and communities battle for survival.

The essence of tiredness is unsustainability. When we are tired, we know we can’t carry on in the same way for long. So in addressing tiredness we address the problem of unsustainability.

The natural response to the experience of tiredness is to rest. However, modern consumer culture doesn’t like rest; “Time is money,” we are told. It must therefore be filled with activity. Every second saved by a dishwasher or car must be paid back double in longer working hours and shopping. Even rest is commercialised and repackaged as ‘leisure’. In the gym, exercise (which is freely available in the nearest park) is sold at exclusive rates so that one can be seen doing it whilst watching adverts on television.

Returning to truly replenishing forms of rest will demand a re-evaluation of tiredness. It may be helpful to think in terms of seven kinds of tiredness, all of which interlink and each of which leads to negative personal, social and ecological consequences when we do not rest. There are also replenishing practices in every culture and religion which build much-needed rest into the rhythms of our lives.

The first kind of tiredness is sleepiness. When we do not sleep properly, compassion, creativity, imagination and reason are lost in order for the brain to run on depleted energy, and the reptilian ‘fight-or-flight’ brain takes over. Many psychiatrists are now convinced that depression is a symptom of sleep loss, rather than the other way around. A shortage of sleep is associated with obesity, road accidents, torture and war. In ecological terms, twenty-four-hour culture means more emissions and more consumption of the Earth’s limited resources.

The solution to sleepiness is sleep. When the Emperor of Persia asked his Sufi master how best to renew his soul, he was told to sleep as much as possible because “The longer you sleep, the less you will oppress!” We sacrifice sleep for more time, but that time becomes less fulfilling. Sleep was the natural way to spend the dark hours, which we now fill with bland TV.

The second kind of tiredness is fatigue: a tiredness of activity. We live in a hyperactive culture where more is continually demanded of us. Trades Unions have to fight to maintain holiday allowances and working hours legislation. Ordinary life proceeds at a pace which does not belong to the human scale, but to the industrial scale. Fossil fuels allow us to travel great distances at inhuman speeds without apparently feeling tired. The tiredness we would have felt does not simply disappear, but gets displaced onto the ecosystems which support our existence. It turns out that the toddler was right who observed the aeroplane “scratching the sky”.

I used to look askance at evangelical Christian sportspeople, mostly American, who would not compete on a Sunday. Now I think we should follow their example. We are tempted not to rest because we think we will produce more, but what we produce is less wonderful. In a culture so dependent on activity, rest becomes a powerful form of protest and a catalyst for change. How ironic that ‘activists’ developed ‘passive’ resistance as a protest tool! Striking and working to rule are two methods which prevent workers from being exploited, which was also a stated aim of the Torah’s fourth commandment, to keep the Sabbath.

The third kind of tiredness is ennui, which is tiredness of stasis. In the Greek myth, Sisyphus, the king of Corinth, is punished for interrupting the cycle of birth and death, by being sentenced to push a boulder up a steep hill. Just as he approaches the top, the rock slips from his grasp and rolls back down, so he has to start again, this maddening cycle continuing for all eternity. Ennui is all about that feeling of being stuck in a rut, of going nowhere.

It is extraordinary that in our hyperactive society so many people are bored. Bored young people hang around the streets causing trouble. Bored soldiers commit acts of atrocity in military prisons. Bored voters don’t care who wins. A workforce is forced to choose between the boredom of the production line and the boredom of unemployment. Television, computer games and Ritalin screen us temporarily from the effects of boredom, but it comes back to haunt us in mental ill-health, addiction, crime and disease.

It seems logical that the antidote to ennui is activity. However, as we have seen, we are very active – even hyperactive. What we need are activities which involve the whole person in a valuable process, to replace activities which isolate mind from body. There are many sources of wisdom to help us here. Brother Andrew, Gandhi, Basava, Julian of Norwich and others viewed work as sacred. Johan Huizinga showed how fundamental play is to human welfare, and in the Kama Sutra the spiritual significance of sex is studied. Martial arts in general developed as forms of meditation, ritualising movement in order to replenish body and mind. In agriculture one alternative to a static monoculture is crop rotation. The movement, through rotation, of the crop provides replenishment to soil.

The fourth kind of tiredness is satiation, which is tiredness of consumption. Our society has an obesity problem which extends far beyond Body Mass Index. Shopping is our chief ‘leisure activity’. The act of purchase has been fetishised so that it now has little to do with the value of what is being purchased. I have heard shoppers speak freely of the emptiness of the whole experience in a way that is strikingly reminiscent of sufferers from bulimia who gorge before making themselves sick. We continue to consume rapaciously because we are wedded to ownership, but the real effects of satiation are unwelcome. They first show up in the environment, where the raw materials for all this consumption must be found. Then they appear in unequal societies and in unjust legislation in favour of the obscenely wealthy. Over-consumption is the root cause of all poverty.

The answer is sacrifice. To sacrifice something is to offer it up wholly. Every year the entire Muslim population fasts during daylight hours for the month of Ramadan. This is a striking example of the use of sacrifice for the benefit of a whole community. Christians and Jews tithe, and Muslims give Zakat. Sikhs practise hospitality and share food (Langar), monks take vows of poverty, vegetarians and vegans refrain from eating meat, and ethical consumers refuse to buy the shiny trinkets constantly advertised. These are all examples of sacrifice. Paradoxically, they all make the practitioner richer through better relationships.

The fifth kind of tiredness is despair, which is tiredness of the effort to maintain positive expectations. This is a matter of real relationships. Consider a mother who hopes for the best for her child. This hope is tested when she feels powerless to influence the child’s future, and may even fail if the child dies or the relationship breaks down.

The reason why despair is becoming more prevalent is that the value of real relationships is being undermined. For instance, it is possible to form a meaningful friendship with a local baker which may even influence the way the business is run. But a meaningful relationship with the staff in a supermarket is not only pointless in terms of influencing business practice, but nearly impossible. That’s why it makes sense to remove staff from some checkouts altogether, in favour of self-service machines overseen by security staff. Even good people in powerful corporate positions are unable to change their institutions: the chief executive of food chain Iceland was fired for trying to make the store GM-free, because he failed in his legal responsibility to prioritise profit for the shareholders. The huge distances and abstractions introduced everywhere in society, from absent fathers and landlords to anonymous shareholders and faraway sweatshops, all leave us struggling to maintain positive expectations. We have handed over power to corporations in the pursuit of individual freedom from responsibility, only to discover that our freedom was always dependent on good relationships and healthy communities.

Compassion is the antidote to failing expectations. It would take extreme circumstances to break the mother’s expectation for her child, because she identifies so strongly with her child through compassion. Compassion allows us to build stronger relationships. It allows us to walk mentally and emotionally in the shoes of those who are exploited and marginalised. It allows us to understand that mountains, rocks, rivers, birds and butterflies are sacred. The distances become smaller and the rifts are more easily healed. Trust returns and communities emerge.

Compassion is a central tenet in every spiritual tradition. The Dalai Lama has placed particular emphasis on it, saying that “caring for our neighbours’ interests is essentially caring for our own future.” Those who practise meditation testify to the replenishing nature of compassion.

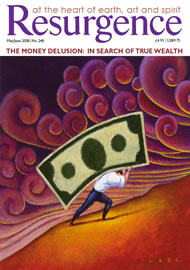

The sixth kind of tiredness is disillusionment. We are living at a time of disillusionment. In Europe we have moved the foundation for our culture’s value systems from Christianity to capitalist materialism. Now we are increasingly aware that capitalism is failing to make sense of our lives because money is not making us happy. But many who are ready to change their minds are not aware of any alternative. So they carry on rushing around, making money, buying temporary happiness in the knowledge that it won’t last. The advertising industry becomes more and more adept at bolstering our flagging faith in owning stuff, and pseudo-spiritual cults proliferate to fill the void. As the recent sub-prime investment crisis revealed, the less faith we have in the American dream, the more we imperil our phantom economy of promises, for that is all that money really is.

Replenishment in this existential crisis comes from true education. Education gives us the intellectual and cultural resources and experiences with which to create new interpretations and meanings from old truths. When our education system is weak in terms of its method, we are vulnerable to the existential angst of disillusionment.

The seventh kind of tiredness is stress, which could be defined as tiredness of coping with the frustration of limitations. It encompasses all the other kinds of tiredness and also comes in distilled forms of its own. Think of the telesales operator who is given a target of sales to achieve but no freedom about how to achieve it. She or he must stick to the script, go systematically through the phone numbers, and never hang up on the time-waster. This produces a kind of mental claustrophobia, a feeling of being cramped.

There is hardly any need to elaborate on the prevalence of stress in our society. Every form of escapism is a way of dealing with stress. Violence and madness are the fruit of stress. In ecological terms we have already become insanely violent. We are at the point of risking our own extinction, yet we find ways to justify new runways, new wars, space tourism and drilling for oil under melting arctic ice. In describing madness, G. K. Chesterton remarked: “A small circle is quite as infinite as a large circle…there is such a thing as a small and cramped eternity.” By leaving Nature out of our economic and cultural equations we are trapped in just such a cramped eternity. Jesus could have gone further. In gaining the whole world we lose not only our souls. We lose the whole world as well.

The replenishment needed in time of stress is meditation. I use the word in the broadest possible sense, including prayer, contemplation and mindful living. The characteristics of meditation are a sense of the suspension of time because of becoming immersed in the present; harmlessness; the involvement of the whole person; and the experience of receiving. In this way, just as stress encompasses all the other kinds of tiredness, so all their respective kinds of rest and replenishment can be practised as forms of meditation. And just as stress can be experienced separately, so the pure meditative forms deal directly with stress by opening up inner space and giving a sense of freedom within, even in the most frustrating situations. I call this kind of meditation Radical Rest.

WHEN ROSA PARKS refused to give up her Alabama bus seat she said it was just because she was tired. In recognising and respecting her tiredness more than the rules of her day, and remaining in her seat restfully, she helped to transform her civilisation. Perhaps the key to regenerating our exhausted world is simply to have a good rest.