British sculptor Antony Gormley in conversation with Jan van Boeckel about his work and inspiration.

At some point during your stay in India in the 1970’s you were faced with a choice between the spiritual life and the artist’s life.

Yes, it’s interesting; I did have a choice to make, in 1973, as to whether I was going to carry on with my Buddhist studies and Vipassanā meditation and become a fully integrated monk and meditator within the Theravadā tradition, or trying to do something else with my life. I could put the tools of what two years of fairly consistent and intensive Vipassanā meditation had given me to another kind of use, and that’s what I decided to do.

In the late sixties and early seventies there were a lot of Westerners around, trying to wear alternative clothing and find a different cultural context but I did not want to escape my own history. I was more interested in bringing something into the home mix.

In the end, I felt that it was my responsibility to try to come back to Britain to fulfil some kind of creative role and maybe bring what insight I had arrived at in India back into that stream of development. But certainly those years of intense meditation remain the foundation of my work. It was the opening of the door to a new kind of knowledge, knowledge that was about first-hand experience. Using the conditions of existence as a kind of test site for asking questions about what it means to be alive, what it means to be conscious. And using the body both as an instrument but also as a kind of arena, or landscape, for a kind of investigation or journey. I think I am still there; that is still at the heart of my work: looking at the body not as an image, not as an icon to be used for its symbolic or narrative purposes, but the body as an open place of inquiry and exploration that is constantly changing, that has no defined characteristics and we just have to watch, to attend to.

The most recent attempts I have made to think about the body as an open zone is using the language of foams or the way that bubbles aggregate. Think of foam, when you have a bubble bath or when you are washing up, or in the head of a beer: it is the most fugitive, evanescent, transforming form. A soap bubble has a perfect form, and then slowly disintegrates. So it is a very ephemeral thing. And I think that is maybe where I am going now in my evocation of the body. It may have something to do with my age, and the fact that I am very conscious now of things breaking down, of me in the second half of my life.

All of the atoms which originated somewhere out there in an expanded universe, are going to be taken back into the circulation of mass and energy; that is the physical conditions of our existence. Maybe as a result of meditation I do not find that frightening, it is rather comforting. It is a bit like surfing, we do it while we can and then the wave goes back into the sea. That’s an image of a Buddhist notion of incarnation: that the whole rising and disappearing of lives and forms is a kind of endless mystery.

In connection to this aspect of ephemerality, it would be interesting if you could talk about your work called “Still.” Still, in its primary form, is simply a lead box, a lead skin made around a sleeping child, age six days. And you could think of this child sleeping on the breast or on the stomach of the mother, close to the place where the child grew in the womb. But the sculpture is as much about its removal from that position on the belly and its exposure to a wider world. It is a small female child that is calm, and in contact with a supporting surface. But that supporting surface has moved from being the belly of the mother to being the floor. For many people that is very shocking, this very small object that is very evidently human that is somehow abandoned. I often show it alone in a big room. Particularly female people find it very poignant. Whether it has to do with abortions that they might have suffered, or the feeling of their own isolation in space, but people have become very emotional.

Our bodies come out of other bodies. In a sense our primary experience is of dwelling within the realm of another. We learn how to listen, how to move, how to attend to the world, within a totally protected realm. Then, at birth, that is taken away from us. We are made into an object that in a sense is separated by space and skin. We are always in a relational field. There are a few moments, maybe in intimate love or moments of total immersion in an immersion tank, where we might recover something of that primal condition. But in the end, we are born alone and we die alone.

In a sense, that is the human condition: that we are lost in space, from the moment that we separate from the body that contained us originally. This could be a tragedy, a kind of existential loss, but I don’t think it is at all. I don’t think of the condition of “aloneness” of the human consciousness as being a limitation. It’s actually the great challenge and inspiration that each of us has. In a way we are spaceships. At that moment of birth we set upon a journey in time and space, and we have to use it as well as we can.

People say about the work: “Oh, it is all about isolation and loneliness and the contemporary condition of alienation.” Well, it might be, for those who want it to be. But I would say that to be fully human, is always a balance between two states: together and apart. And one is to be alone, aware and attentive to being itself. And that can only happen in a state of silent isolation. And the weird thing is that that is also a state of togetherness, togetherness with being. That is something that Buddhism understands absolutely: that the state of being is not limited to an individual consciousness that is isolated. If you are within it totally, it embraces all being, all living things. And not just all living things, all things that are: the vibrations within a quartz stone, the life in a tree or a blade of grass, the movement of air within our atmosphere. Somehow they are all extensions of our consciousness, our ability to plug in to consciousness. And to become aware of that connectivity, you have to accept your position, as a point in space at large.

The other condition of human being is that we are relational animals, and we have a primary relationship to the mother and to the lover and to the child that we bring into the world ourselves. It is those two: the acknowledgement of the fact that each of us has a unique journey to make which is our own, and the acknowledgement of the fact that we are all, in some senses, the sum of our relationships with others. And those two, in an ideal world, go together. But often it is difficult to keep them in balance.

Following up on that, the skin being the boundary, what is the relation between inside and outside?

I was obsessed with this notion of what was the skin, where do things begin and end? Can we talk of a bounding condition of human life? The skin is the largest organ of the human body, the best provided with nerve endings. It’s the most receptive and intelligent organ in the body because it exists at the edge. As I am sitting now I am aware there is a draft coming from under the door and I can feel currents of air around the bottom of my chin and the up side of my leg. There is a sense in which the skin is like a Geiger counter, if you attend to it is continually –– calibrating your experience of your environment. And I guess the idea that, the Aristotelian distinction between substance and appearance was always about the skin, was always about the surface of things. I am able to see you because light is falling on your skin. The skin is the necessary facilitator.

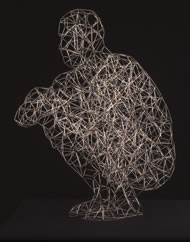

The question for me is always: why are we so obsessed with this visual limit? In the early work I was continually making the skin even more present, and that was just my way of asking the question: What is it? What is it, this surface that surrounds us? What makes it different from the surfaces that surround other objects that we share the world with? The breakthrough came in the mid-nineties when I realized that it didn’t have to be absolute and you could make it more and more open. And I started by just drilling hundreds of holes in the skin of the objects that I was making. But I was still making cases. And then I realized that you could make up surfaces – not out of continuous sheets of something, but out of little elements, that you could think of as being “sparks” or “needles.” I started with rings and nails, short lengths of steel. And I suppose I am still working in that way, thinking about the skin, almost as a sieve, completely open.

Did the condition of us, as Westerners, as modern people, change in the course of history when people like Leonardo started to open the skin, and our whole perception has changed of what the body is about?

In the eighteenth century with pioneers like Cuyp, anatomy became the new “Terra Incognita,” with its pioneers of a colonization of the territory of the body, finding its great rivers, its hidden continents. The empirical idea about discovering the relationships between skin, muscle, bone, Harvey’s analysis of the circulation of the blood, looking at the neural system and central nervous system and its extraordinary branching nerves and neurones: the physical landscape is fascinating but I’m not really interested in that. The notion of the empirical study of the body as a machine was very much part of the Enlightenment project, but it blinded us to other aspects of embodiment.

I am more interested in bringing the understandings of post-particle physics to the notion of the body as conscious material in space. So I probably start with the skin, and exploding the skin, but then start asking about: what is, as it were, what is “body consciousness”? In meditation you can do it, you can put your full concentration for example on your heart, or lungs, and you can get a direct contact with those completely aleatoric, spontaneous, autonomous rhythm systems that exist within the body. But actually that takes a bit of training and I don’t think it is terribly relevant. In meditation, you don’t go round identifying specific organs. Its purpose is to escape from that taxonomy of the body, the body about naming parts and functions, and seeing it as a whole, and seeing it as an energy system, or seeing it as a field of sensation.

So my interest has been in making the body porous and thinking of it as a place rather than as a thing. I am not interested in dissecting it; the body in pieces, as in anatomy, is not of interest for me. But I am interested in somehow articulating this zone of sensation in a way that is recognizable from post-particular physics, from the Podolsky-Rosen experiment onwards. Where one is less concerned with Newtonian ideas about universal laws and particular objects that, as it were, demonstrate those laws, then with matrixes, fields, vectors, flows, everything that has come as a result of Einstein, Bohm, Niels-Bohr – all of the pioneers of a new way of looking at matter.

Is in this context the word “respect” relevant, respect for what the body is about?

I don’t know. The body is more interesting than a stone, because it has got a mind in it. But I would say: that’s only a matter of degree. Maybe more importantly the body is of interest because we live inside it, rather than all the other things that we have to observe from the outside. So in terms of physics, the investigation of what this bit of matter is like is participatory in a way that it can never achieved through an electron microscope. Even though, the results of both might be quite similar.

One of my newest works is called Exposure because I wanted to make something about consciousness and that bigger body of nature. There were a lot of moments when it looked like this sculpture was not going to happen because we didn’t have enough money or we didn’t find the right person to make it. But I really wanted to do it because the site is so extraordinary. The site, in Lelystad, in the Netherlands, is truly elemental, where you have sky, and sea, and a little bit of earth, but not very much. So the only “mass” in the view from the city onto the Zuiderzee, on this line of the polder, is this body form, which for most people you’ll see from a kilometre away and will have no idea about its true size, apart from when somebody is walking along underneath it. So it has a scalein relation to this, if you like, wider body, of the interpenetration of the elements, and it’s open. So this exposure is the abandonment of this industrially produced thing to the elements, the exposure of it to the elements.

But it is also about the exposure of the body as an open space, so that idea of it being as a sieve, or a net or an antenna, and the fact that it is, of all of the work, it is a very good one in relation to this meditative sense. You could say this is a field function that is defined by a bounding surface, but the surface is completely open. And within that field there are hundreds of nodes, the most complex has 27 trajectories coming into it. The simplest are the ones on the surface which only have three. What we were talking about is a connectivity system. I’ve used the biggest nodes, the ones with the largest number of elements coming together in one point, are in the centre of the head, the heart, the stomach and the genitals. They are reformulating anatomy in relation to thinking about the body itself as an energy field. That energy field is then placed, as it were, within the big energy field of the exchange between light, air, water, and space at large.

Is there a relationship between ‘exposure’ and vulnerability?

Yes, I think so. The irony about Exposure is that here is a body that is taking up one of the minimal positions, almost back into the foetal position, and yet, it is very big! It is a very large object, talking about the body in its most compressed form. And that compressed form, in a sense, is about the same thing we were talking about with Still: the idea of the universal human condition of being “lost in space.”

So that’s Exposure. The other side of that is Quantum Cloud, where there is no bounding condition, there is simply a matrix, which exactly refers to the Podolksy-Rosen paradox, which is: that if you know a particle’s position, you won’t know its speed, if you know its speed, you won’t know its position. So the idea of this aleatorical, completely random, Brownian motion of elements in space, that kind of connect, and at the core you have a condensation that vaguely might give you the idea that this is a human space. The level of uncertainty is very important, that you are not sure whether this field is a product of the body, or the body is a product of the field.

For me it is probably the same question, being asked in a different way by Exposure, which is, where does this extraordinary combination of mind and matter that constitutes a human life, fit? Where does the human fit in the scheme of things? You could say that is a philosophical question. So I am doing a kind of physical thinking, materialising questions. This is the absolute antithesis of you could say the traditional “public statue,” like old Lely, up on his column, in Lelystad; you know exactly who he is, why he is there, why he is celebrated, because you know he made it possible for that town to be there in the first place. There are no further questions to be asked about what the nature of this representation is. Well, my Exposure is completely the opposite. What the hell is this thing doing there? What is it? How is it? Who is it for? How am I supposed to relate to it? All of those are completely open questions. And in a sense, you as a viewer, have to participate physically in asking them. And whether you ever get an answer I don’t know. But, you know, you have to go, and see it, you might say to yourself: “Well that looks odd, I better go and check it out.” Maybe you walk, or you bicycle out, and have a look from close up. And the invitation that it offers you is: “Come and have a look, come and make a physical journey, around, underneath.” The idea, that this is a kind of question in physical form, is very important to me. This is about opening up the world, rather than defining it; not talking about known facts or entities, but saying: “Well, maybe we’re not quite sure where we fit in the scheme of things.”

Maybe related to this: art as a process, art as a way of engaging, a way of learning: in what way would you say that the process of art making gives us knowledge that any other endeavour does not give us?

I am worried about that notion of “knowledge.” Eliot said: “Where is the understanding we have lost in knowledge?” Knowledge suggests always defined quantities and understanding suggests that you might not, that it is a process that is open-ended. This is the crisis, the crisis of a knowledge industry, you might say. The way that we have used mental tools to gain advantage over other species, over the raw materials of the earth, in a sense is our problem now. The whole idea about ‘the rational’, the kind of Cartesian inevitability of the empiric. And if we replace knowledge with understanding, we recognize that there are maybe other ways of using human consciousness that are not necessarily about getting advantage. Understanding itself is a process that might not have defined ends.

I think that art can absolutely be a catalyst for a process of understanding, a kind of empathy, a process of engagement. It is only really in the last five hundred years, in Western terms, that art has become singularly about high-valued decoration and the elite. I think it is a very good thing to go back to other models of art, where it is much more about a collective expression of what it feels like to be alive. So, if we take an anthropological model and think of the songs, the dances, the kinds of architecture of non-urban, non-literary societies, I would say they are profoundly artistic. Art finally is the way that life expresses itself.

You once said that when you were in India, you saw people sleeping on the street, and that somehow triggered your fascination with the body.

The beauty of those experiences of seeing people sleeping on railway stations, on sidewalks, in India, was that it reinforced this same thing that we were talking about with Still: here is an isolated individual in space, vulnerable in a way that we don’t see, or is not expressed in the West so generously. We have the huddled bodies of the homeless that we see in the shop windows or in empty lots in our inner cities. But in India, it is a collective expression, this acceptance of the body as our first home. I find that very beautiful, just seeing, in the early morning, these isolated and abstracted bodies, just covered by a thin membrane of cloth. And, often just with these two shoes parked, or a radio or something. I find it very moving and touching that in India that was all that was necessary to declare an intimate and individual place in the world. You could just wrap yourself up in you dhoti, lie on a mat, and you would be respected as if you had a palace around you.

How did the experience of being in meditation help you when a body mould was made of you for two hours or so? I think most other people would experience some form of extreme claustrophobia.

It is still fairly scary, if it’s a very tight pose. It can be extremely painful. But on the whole, for the last 4, 5 years, I have been doing vertical poses. And that’s not painful at all. I find it a wonderful thing to do. I think of the process as being one of a kind of transfer of concentration; that you just have to be. It is very important to me that all of the work is about being. Not about action. Not about a frozen moment in a narrative of action. It’s about being, not doing. And meditation helps enormously in that concentrated attention on being.

It is clear that once you accept this condition, of stillness and silence, that the mind becomes incredibly free. You are alert, aware. But all of those normal instruments of direct action – walking or making, doing things, having an effect on the world – are taken away. And that’s like the biggest holiday you can ever have! Because the mind can go everywhere, when the body is really still. In meditation that is one of the things you should try to stop! But when you are being moulded, it is a marvellous feeling of this expansion of the mind. The Tibetans call it the “sky nature” of mind, and I think that is the nature of mind. Our minds want to wander, they want to expand, they want to be limitless.