TWO OF IRAN’S finest film directors, Marziyeh Meshkini and Samira Makhmalbaf, have each made a film set in – if it’s not too soon to use the phrase – post-Taliban Kabul. These two films are so penetrating, so accomplished beyond the grasp of just about any Western cinema in the telling yet unlaboured use of metaphor, so compassionate and disquieting, that maybe Resurgence readers will welcome a brief – particularly since the films have little hope of a showing in mainstream cinemas.

Both films examine the predicament of women in war-stricken Afghanistan, and are factually so powerful that it would be easy to see them as skilled polemical documentaries. But they go beyond this to achieve imaginatively unique insight into the way war causes division and breakdown in the core-being of society. Any way. Every war. All wars.

Both films use a single chilling image to point to the outside force that imposes the climate of war. In one it is the glimpse of a distant vast bomber soundless in the misty blue sky; in the other the sudden flight of black gunships over a remote mountain road. In a moment one is alive to this psychic insurgency of violence stemming, it would seem, from the detached power-concerns of a male-driven universe. From this climate unfolds the particular that is the subject of both films: how the idiom of war hands the situation to the devices of the masculine because, where brutality rules, the masculine is more powerfully equipped and less shackled by feeling. It is a situation in which the feminine cannot operate. Survival in a brutalised world requires the rejection of feeling – the suppression of the feminine.

Makhmalbaf’s At Five in the Afternoon (a line from a doom-laden Lorca poem) is set in the afternoon of the overthrow of the Taliban when young women are daring to seek education and to dream of genuine equality of opportunity. One, the film’s central character, daydreams that it now could be possible for even her to become President. A dream that we see crumble as it runs into the actualities of life where patriarchy is still in exclusive command – a patriarchy portrayed as that of demented old men, the puppets of an ossified but still inherently divisive and self-

destroying fundamentalism.

We are drawn painfully into her gradual disillusionment – while always wondering, is hope still possible? She finds refuge for her old father, her

sister-in-law, the baby and the horse in the ruins of an old patriarchal palace. And, typical of the unlaboured use of metaphor, Makhmalbaf shows her searching for water (the feminine element of life, feeling and renewal) in that broken place. At last she hears somewhere the slow, persistent drip… drip… but is unable to locate it. Even so, could it be the intimation of an abiding hope? And if so, is it echoed at the end when the two women leave behind the dead child with the powerless old man, and walk into the wilderness where, they’ve been told, they will find water?

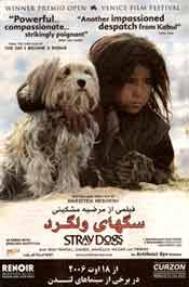

Meshkini’s Stray Dogs sees this war-torn situation from another viewpoint. A mother, accepting finally that her husband has been killed in the war, makes it possible to provide for their two children by taking up with another man. The husband returns, declares her an adulteress and, true to metaphor, has her locked away. The film’s focus is on the two children – a boy aged maybe ten, and his sister, eight. In a world of violent dysfunction they appear as the last embodiment of humanity. Their relationship is one of immediate and archetypal meaning – she the guiding authority of the heart, he the provider and protector (or however you choose to see it). In other words, an image that doesn’t make the mistake of idealising the feminine at the expense of the masculine, but sees the pair of them ‘fit for purpose’ only when unified in both need and love – that fragile priceless union is presented not only as all there is to live for, but also as the condition of survival. Exquisite, extraordinary performances.

At the outset the children are allowed to be with their mother in a prison, and to venture out to somehow provide for the three of them. But then some shift of policy shuts the door, and they are left to look after themselves in the brutal townscape. Their father disowns them. In desperation they conclude that in order to rejoin their mother they must themselves do something to be imprisoned. This ends in disaster: the boy inside, the girl shut out on the streets. The last – and we experience it as our last – integrity has been broken. Somewhere above, a vast silent bomber dominates the sky.

Both films demonstrate an incidental irony – that directing the camera is an eye of absolute humanity, and one able, it seems, to divine at least an aspect of beauty in everything it sees – an artistry that is unaccountably and universally generous. But be warned: both films are unbearably painful. Or maybe not quite, because this pain is a way of accepting the truth, and relating this truth to the situation in the world. To have seen it, to have realised the pain so fully: there has to be in that some offer of hope.

Both films are available on DVD.