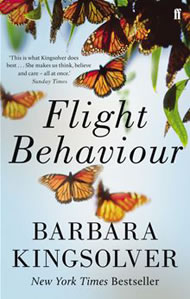

Dellarobia Turnbow does not like her name, her mother-in-law or the fact she is an orphan. She is even less impressed with where she has fetched up in life – not yet 30 and trapped in a loveless marriage thanks to a shotgun wedding that followed an unplanned teenage pregnancy that never even went to term.

Already, I like her. A lot.

We first meet Dellarobia as she heads up the dirt track in her charity-shop cowboy boots for an ill-advised and illicit rendezvous with a most unsuitable young man. The fact that nothing comes of this intended adultery is by-the-by because what stops Dellarobia, literally, in her tracks is a miracle: a beacon of hope she believes has been sent by God to show her he has not forgotten her or her struggling family. A thing that she finds deeply touching and beautiful beyond words.

If Dellarobia were just a little older – say 40 or even 50 – then she would know that what might look like a miracle to one person may look very different to another, and thus Barbara Kingsolver’s new story unfolds.

This is a rollicking good read, albeit with quite a few underlying barbs. Dellarobia’s miracle turns out to be the unexpected and unprecedented arrival of the golden orange Monarch butterflies that have swarmed the trees behind the failing farm in the Appalachians where Dellarobia and her family struggle to make any ends meet. (The cover image gives this away, so I am not spoiling anything by naming the species.)

As word of this miracle/tragedy spreads (including to and through a very blinkered and celebrity-obsessed media), along comes our intriguing and handsome scientist – a Monarch butterfly specialist who opens Dellarobia’s eyes to an impoverishment of the natural world that dwarfs her own feelings of poverty and to the terrible reality of the trigger for the butterflies’ (also) landing so off course: climate change.

Beneath the unfolding story of what to do – if anything – about this disaster, Kingsolver pricks at the complacency of a green movement so good at talking about the issues but perhaps less good at working together for change or at addressing those issues in any way relevant to the unconverted (like Dellarobia and everyone she knows).

“Worries about the environment are not for people like us,” Dellarobia tells the scientist, who lies awake at night fretting about climate change. “Everyone chooses,” he replies. “A person can face up to a difficult truth or run away from it.”

It is a response that makes the scientist look stupid. We are now two-thirds of the way through our story and so we know that if there is one thing Dellarobia and her kinsfolk are not, it is cowardly, profligate or uncaring. In fact when a climate change protester camped outside her home invites Dellarobia to sign a ‘pledge’ to help save the planet by changing her consumer choices, he soon realises that poverty will make your choices for you, and that because of this, her carbon footprint is probably a fraction of his own. Happily, he quickly shuts up.

It is the cry I hear, over and over, from the fragmented greens. “How do we get people to care?” I have even heard people who care so much about the planet that they think it a good idea to simply terrify others into caring too!

The most haunting line in the whole book is terrifying too. It comes when the already erratic weather turns, threatening to decimate what is left of Dellarobia’s butterfly population.

“Not everyone has the stomach to watch an extinction,” the scientist tells her.

“So you’re one of the people who can?” she asks him.

“If someone you loved was dying, what would you do?”

As the nature of the loss – his loss, her loss, your loss and mine – hits her fully, Dellarobia’s response shows you don’t need any of the things you can buy to make a difference. And it doesn’t matter whether you are rich or poor or in between. You just need to care enough.

“You do everything you can,” she says. “And then, I guess, everything you can’t. You keep doing, so your heart won’t stop.”

And there speaks someone who cares. More than enough.