In an age obsessed by gigantism, we live under the illusion that “big is big”: that big produces more and that big is more powerful. We believe that we need big farms, big dams, big corporations to meet our needs for food and water. Giant corporations have grown bigger, with just five companies now controlling the seed supply, the food supply and the water supply.

The reality is that “small is big”, ecologically, economically and politically.

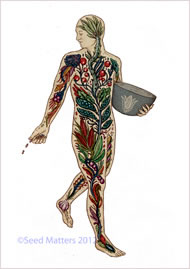

At the ecological level we know that in a small seed lies the potential of the largest tree. In a seed there is the potential for multiplication into thousands and millions of seeds. And in each of the thousands of those seeds are thousands and millions more. This is abundance. That is why in India whilst sowing our seeds we pray: “May this seed be exhaustless.”

Yet when seed is patented or biologically terminated by giant corporations, it cannot multiply or be reproduced. It produces zero seeds. The motto then seems to be: “May this seed get exhausted so that our profits are exhaustless.”

Seeds become our food. And small is big in the food economy. Small, biodiverse farms produce more than large farms, as we have found on our Navdanya farms (www.navdanya.org).

We can double outputs and income through conserving seeds and intensifying biodiversity. The fact that small is big in agriculture has been known all along, yet big has been privileged as the basis of our food security.

India’s former prime minister Charan Singh, himself an agricultural economist, said that small farms are more productive than large farms: “Agriculture being a life process, in actual practice, under given conditions, yields per acre decline as the size of farm increases (in other words, as the application of human labour and supervision per acre decreases). [These] results are well nigh universal: output per acre of investments is higher on small farms than on large farms. Thus, if a crowded, capital scarce country like India has a choice between a single 100-acre farm and forty 2.5-acre farms, the capital cost to the national economy will be less if the country chooses the small farms.”

The future of food security in India and worldwide lies in protecting and promoting the small farmers.

Small farms produce more food than large industrial farms because the small farmers give more care to the soil, to plants and to animals, and thus intensify biodiversity, not external chemical inputs. As farms increase in size, they replace labour with fossil fuels for farm machinery, and toxic chemicals for the caring work of farmers. Food production per acre actually goes down, but productivity is manipulated in two ways to project large farms as more productive.

First, the only input counted is labour, so the more small farmers and family farmers are displaced and replaced by chemicals and machines, the more false calculus says productivity has increased. A social tragedy morphs into a myth of more. And this myth of more is then sold to the world as a solution to hunger.

The second trick is to measure not the total output of a farm, but only the ‘yield’ of a monoculture commodity. The monoculture of the mind shuts out the bounty of biodiversity, and presents low food output as increased production.

Navdanya’s assessment, Health per Acre, shows that the more biodiversity on a farm, the higher the nutrition per acre. And it is only small farms that can be biodiverse.

Small is big when it comes to food. In spite of all subsidies going to large farms, in spite of all policies promoting industrial agriculture, even today 72% of food comes from small farms, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. If we add kitchen and urban gardens to this figure, most of the food people eat is still grown on a small scale.

What is growing on large farms is not food, but commodities. Only 10% of the corn and soya taking over world agriculture is eaten; the rest goes to drive cars as biofuel, or to torture animals in factory farms as feed. Small feeds the world. Big spreads its poisons and creates more hunger.

The 2013 Trade and Environment Review of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Wake up before it is too late: Make agriculture truly sustainable now for food security in a changing climate, states that monoculture and industrial farming methods are not providing sufficient affordable food where it is needed, and are causing mounting and unsustainable environmental damage.

The report asserts that farming in rich and poor nations alike should shift from monoculture towards greater varieties of crops, reduced use of fertilisers and other inputs, greater support for small-scale farmers, and more locally focused production and consumption of food.

The 2012 International Labour Organization report Working towards Sustainable Development: Opportunities for Decent Work and Social Inclusion in a Green Economy shows that small-scale agriculture is the solution to the ecological crisis, the food crisis and the crisis of work and employment. It cites examples of how small farms in Africa have increased food production through ecological agriculture. In a project involving 1,000 farmers in South Nyanza, Kenya, who are cultivating two hectares each on average, crop yields have risen by 2–4 tonnes per hectare since converting to organic farming. In another case, the incomes of some 30,000 smallholders in Thika, Kenya rose by 50% within three years of converting.

The International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development confirms that small ecological farms are a more effective solution to world hunger than the Green Revolution or genetic engineering.

Small is the nature of the food web and the water cycle. For both food and water, small conserves Nature and other species, while providing more to humans. Big is the old big in its ecological destruction, and small is the new big when it comes to providing food and water.