Biophilia, n.: an instinctive bond between human beings and other living systems; an innate love for the natural world

It is estimated that around 3% of charitable donations goes towards protecting the environment and, of that, only a fraction is targeted effectively. Synchronicity Earth is a young, London-based charity working to identify the gaps in global conservation in order to better serve the environment we live in and the species we live amongst. Underpinned by holistic thinking and evidence-based action, Synchronicity Earth’s mission is to increase and improve the impact of environmental philanthropy to effect change where it is most needed. An innovative and inspiring way of raising awareness and concern for biodiversity is in its use of creativity to promote and encourage the changes in thought needed to rekindle biophilia.

Biophilia is Synchronicity Earth’s campaign to help bring human society back into alignment with the living world. According to Laura Miller, the charity’s executive director, “Biophilia is more than just the love of the natural world. It is a guiding principle that – if followed – would create the conditions for resilient societies that replenish and restore ecosystems; that promote environmental and social justice.” Launching this November, the campaign celebrates 50 years of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, the world’s most comprehensive source of information on the global conservation status of plant, animal and fungus species. Something of a barometer of natural life, the IUCN Red List is an independent inventory compiled by around 9,000 scientists from around the world and includes over 74,000 species, of which approximately 20,000 are threatened by extinction and around 850 are probably extinct.

Although Synchronicity Earth has a comprehensive scientific base, with extensive analysis used to identify priorities for conservation, science doesn’t always compel us to act. Valuing the potential in art’s dialogue with Nature, Biophilia employs artists interested in the complexities of the natural world to engage with ideas emotively: to move people in ways science cannot. Visual narratives offer the emotional and sensory impact needed to engage a wider audience; it can be accessed openly across all areas of society and has the potential to be a process by which we can refocus attention. Art plays a key role in guiding trends that shape and develop culture – society often looks to artists for a visual response to the world – and it is now more than ever, in an age of social media, branding, advertising and the internet, that art can be employed in conservation. Founding Synchronicity Earth trustee Jessica Sweidan says: “Art plays a vital role in making our impacts on the planet visible, challenging us to see what is happening and discuss its implications.”

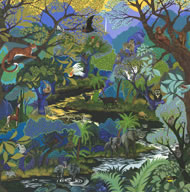

From birds soaring high above mountaintops to sediments on the ocean floor, from gorillas and other endangered species to threatened Indigenous fishing communities, the artists involved in Synchronicity Earth’s recent exhibition at Gallery 8 in central London, Disappearing Nature: Artists Supporting Life on Earth, contemplate our relationship with Nature. Film stills of the African Eagle Owl and Harrier Hawk by leading contemporary artist Jeremy Deller explore notions of the wild and primal, whilst offering a rare close-up of the fanned feathers and glassy eyes of these majestic birds of prey. Dan Holdsworth’s still and contemplative photograph of a barren Icelandic landscape left by a glacier, one of the planet’s great markers of time and evolution, features a concrete bridge in the distance signifying human intervention in the natural landscape. Also exhibiting was Alice Shirley, who has become something of an artist-in-residence for the campaign, with her colourful brush beautifully illustrating the different habitats and species that populate our planet.

Marcus Coates’ photograph Self-Portrait Underground (Worcester) is a playful yet powerful reflection on our relationship with Nature. Self-taken, buried in a pit beneath a meadow with a shutter release in the photographer’s hand, it simulates hiding from destruction by humans. Coates becomes physically part of the field, suggesting a subjectivity that is indistinguishable from its surroundings, yet remains fully visible; it is the “idea of seeing ourselves in Nature, making our identity partial in a way, so we’re not totally autonomous and we haven’t got this screen around us”.

In a discussion at the exhibition’s opening between the anthropologist Jerome Lewis and Marcus Coates, both described the need to see Nature as indistinguishable from ourselves, as Indigenous communities refer to Nature as indistinct from themselves. In Coates’ case art is not about Nature itself but about the relationship between humans and Nature: “it’s not actually the animal itself, it’s the relationship between me and that animal. That’s why I became interested in art. It’s our relationship to it, from a position of sameness, not as separate.”

Our relationship with the ocean is explored by two artists: Tania Kovats, in Where Seas Meet, comprising two connected glass vessels containing seawater from the point where the Tasman Sea meets the Pacific Ocean to the north of New Zealand; and Mariele Neudecker, in her video Dark Years Away. Created in collaboration with Alex Rogers, a leading world marine biologist and adviser, Neudecker’s footage documents an underwater excavator collecting specimens at the bottom of the world’s deepest oceans.

Bringing together artists and scientists over mutual interests and concerns highlights the power of interdisciplinary dialogue. As a panel discussion between artists Zana Briski and Tania Kovats and scientist Simon Stuart – chair of the IUCN Species Survival Commission – showed, art and science share obsessive qualities. Although very different in form, both disciplines require certain measures of curiosity, tenacity and perseverance. There’s a shared desire to communicate their findings and verify the value of their obsessions. However, artistic curiosity doesn’t have to be proved; nor does it comply with the strict rules that science operates under. As Stuart describes how one set of questions leads to another set of questions, becoming more and more detailed and more and more difficult to communicate to the outside world, Kovats describes art’s open and uninhibited investigation. This is where art can work with science, operating in a communicative capacity to relate, to emote and to wonder. Art for conservation’s sake may help rekindle what we know but may be forgetting.

The launch event for Biophilia takes place on Saturday 22 November in the Central Hall of the Natural History Museum. www.synchronicityearth.org