Over the last two and a half million years or so, successive ice ages have smothered much of what is now the British Isles in enormous glaciers, which scoured the land. Each time, following the retreat of the ice, the forests have returned, carpeting the hills and valleys, mountains and estuaries, first with species such as birch and hazel, and then Scots pine, alder, oak, elm, lime, ash, beech, holly, hornbeam and others. After the ice retreated around 11,000 years ago, woodlands once again established themselves, climaxing in almost complete coverage of the archipelago in forest dominated by oak, alder, lime and Scots pine by around 6,000 years ago. A squirrel could have walked and hopped almost from one end of Britain to the other without touching the ground.

Then humans began to arrive. Though in small numbers at first, they nevertheless transformed the landscape, slaughtering animal species that played a role in forest ecology and beginning a process of felling, burning and managing woodland that has, with important variations, expanded and continued to the present day. A densely populated island, Britain today has the lowest forest cover in Europe after Ireland, with some 10% under trees compared to a European average of more than 30%.

But no story is complete without its paradoxes and contradictions. The peoples of these islands have also cherished trees and woodlands – and not merely for their utility as sources of fuel, forage and materials for tools and construction. Recognition of the beauty and the spiritual importance of individual trees and wooded places, and the deep connections they can awaken in us, dates back as far as we know. It may come as a surprise to modern readers that John Evelyn’s Sylva, a treatise on forestry published by the Royal Society in 1664, which placed economic and practical concerns – notably the pressing need to provide sufficient oak to supply England’s navy – front and centre, includes an entire book on sacred and standing groves.

Rapid technological and social change, climate change, flooding and other factors pose massive challenges to our forests and woodlands today. Education, dialogue, practical everyday involvement by citizens, and political engagement have never been more important. The New Sylva, which was published earlier this year on the 350th anniversary of Evelyn’s great work and takes inspiration from its illustrious predecessor, will be a valuable and enduring aid in the struggle.

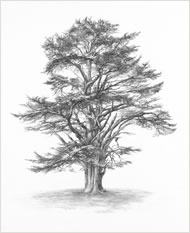

The New Sylva describes the nature of Britain’s diverse and changing trees, their cultivation, their use and their management. Gabriel Hemery’s text is a precise, fascinating, fluent, wide-ranging and hard-headed synthesis: an excellent popular introduction to tree biology and forestry. But the book is more than that. Together with his co-author, Sara Simblet, whose 200 drawings make up at least as substantial a part of the book as its words, Hemery is out to celebrate and inspire passion and love – to bring more readers into the camp of those who, like William Blake, can be moved to tears of joy by a tree. The drawings really are astonishing: they are fine and vivid, combining anatomical precision with qualities that arouse intense emotion – at least among those to whom I have shown the book. The places where they were drawn are listed so that the reader can – and this would be a worthwhile way to spend a good part of one’s time if it were possible – go to observe and meditate upon the originals.

This book is gorgeous, precious and important. I would put it in the hands of a distracted small child or a jaded adult and defy them not to be enchanted. The New Sylva deserves a place alongside a select number of books on our trees and woods, amongst them Roger Deakin’s Wildwood, Richard Mabey’s The Ash and the Beech, Oliver Rackham’s Woodlands and Thomas Pakenham’s Meetings With Remarkable Trees, as well as works by such as George Monbiot in Feral, who are ready to dream boldly about a wild and beautiful future.