Previous generations of architects thought of how architecture could interpret the world, but I think now is the time to think of how architecture can change the world. We architects can assume that role and make a real difference in how people live and behave. – Giancarlo Mazzanti

We are living on the verge of a metropolitan boom. According to the United Nations, two-thirds of the Earth’s people are projected to live in cities by 2050. This urban migration, combined with growth in population, will have a transformative impact. Over the next three and a half decades, the world’s cities are predicted to swell by 2.5 billion people.

Having more urban dwellers may be a boost to human development. Cities can offer better access to basic services and more job opportunities. They can spur efficiency and innovation. They are often hubs of intellectual and cultural richness. And denser living tends to be much more environmentally sustainable. For example, Singapore – a city-state of 5.4 million people – ranked among the top five countries in the 2014 Environmental Performance Index, reflecting urban infrastructure’s contribution to challenges such as sanitation and waste-water treatment.

Yet without deliberate attention modern metropolises will not be synonymous with healthy communities. Abundant research has shown how urban sprawl and a rising dependence on cars reduce opportunities for exercise – and the corresponding impact this has on people’s health. To give just one example, research conducted by the University of Utah found that people who live in communities where it is easy to get around on foot weigh 6–10 pounds less than people who don’t.

And there is another kind of weight to consider, a weight that can burden anyone; a weight that crushes people’s sense of wellbeing, that limits their hope for the future. This is the oppressive weight of social isolation – the lack of social connectedness, of face-to-face human relationships, of feeling a sense of belonging.

Urban living can feel profoundly isolating and lonely, even when people are surrounded by thousands – even millions – of other human beings. Why? In part because so many modern cities have been designed around cars, at the expense of the parks, public plazas and common spaces where people naturally congregate. As Dominic Richards, special advisor to The Prince’s Foundation on Building Community, explains, “when you rely upon a car to get from place to place you lose the miraculous moments where you just bump into people on the street, where you connect with your neighbours, where you are mixing with different kinds of people.”

When those “miraculous moments” are missing, when people feel alienated and alone, it can take an excruciating toll on individuals, families and communities.

I was struck by a survey that the Vancouver Foundation conducted in 2012 to better understand what community issues citizens of that city in western Canada cared about most. To the Foundation’s surprise, the most significant issue was “a growing sense of isolation and disconnection” – the sense that an increasingly individualistic way of life was undermining community caring and engagement.

One in four respondents said they were alone more than they wanted to be. Distressingly, the survey found a correlation between this loneliness and “poorer health, lower trust, and a hardening of attitudes toward other community members”.

These new realities are not limited to Vancouver – and the challenges will only be exacerbated by such demographic trends as more people living alone and the ageing of many industrialised societies.

In the United Kingdom, for example, where roughly 7.7 million people live alone, a recent survey by the organisation Relate found that one in ten Britons doesn’t have a single close friend. In the United States, a 2010 survey by the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) found that 35% of Americans over 45 were lonely – and, as with Vancouver’s experience, there was a significant correlation between loneliness and poor health.

If cities are our future, now is a pivotal moment to think about the future of our cities – remembering, as British architect Ralph Erskine once said, that “the job of buildings is to improve human relations: architecture must ease them, not make them worse.”

Our goal must be to build for belonging, with urban places, spaces and systems that enable the “miraculous moments” of interpersonal interaction that Dominic Richards described. That can mean, for example, thinking about accessible, safe alternatives to private cars, from walkable neighbourhoods to bike lanes to buses. As Enrique Peñalosa, the former mayor of the Colombian capital, Bogotá, once said, an advanced city isn’t one where the poor get around by car: it’s where the rich use public transportation – which is why, during his tenure (1998–2001), he built Bogotá’s first rapid transit system, the TransMilenio bus.

Building for belonging can mean designing cities for the varied dimensions of people’s lives, with mixed-use environments that integrate opportunities to shop, work, learn and relax; where neighbourhoods are walkable, people of different ages and incomes are mixed together, and natural prospects for connection exist, from pedestrian zones to public parks to farmers’ markets.

Building for belonging can also mean prioritising housing quality alongside quantity. In London, for example, where affordable housing is at a premium, developers and community organisations worked together to create the award-winning Highbury Gardens complex in the London district of Islington. With 119 one- to three-bedroom homes, 42% of which are affordable housing, Highbury Gardens combines classical architecture and contemporary amenities, including a beautiful common garden where residents are encouraged to relax, reflect and play. It’s a far cry from the affordable housing strategies of the past, when low-income families were shunted into concrete tower blocks. It also promotes a healthy mix of social tenants, key worker shared-equity purchasers, and full market purchasers, all living together in one development. This contrasts to the usual ghettoisation by income groups that further breaks up and isolates communities.

Another key aspect of building for belonging is respecting local knowledge, and listening to local residents about what they value most. People want to feel a sense of place that connects them to their communities – to the landscape, street life and surroundings that make “where I live” feel special.

There is much modern societies can learn from the experience of traditional cultures. In my home country of Canada, for example, the architecture of Indigenous First Nations peoples was consistent with their values of respect and care – for one another, and for the natural environment. My friend Chief Shawn A-in-chut Atleo explains that the central law of his people, the Nuu-chah-nulth, is tsawalk, which means simply “We are one. We are all connected.” This expresses a worldview based on the interrelationships between all life forms. Chief Atleo recalls listening as a child to the grandmothers of his village singing special songs to the Earth, emphasising the connection between all human activities and natural phenomena. He has told me how the older Nuu-chah-nulth would say, “Even the rocks are alive.”

All Nuu-chah-nulth housing was designed to respect these cultural laws and spirituality, as well as to be appropriate to the climate and local environment. Builders used only the materials they needed. In modern environmental parlance, we’d say they kept their footprint light. But these values of harmony with and stewardship of the land were about more than environmental sustainability. They spoke to a sense of reciprocity and respect for humanity’s oneness with all living things.

One of the most important structures was the wooden longhouse, in which multiple families lived together, with several generations beneath one roof. Made from cedar logs, these long, narrow dwellings were grouped together to form villages. The structure reflected and reinforced cultural norms of helping and learning from one another. For First Nations peoples, being and belonging were two sides of the same coin.

I believe ancient knowledge has a role to play in meeting contemporary challenges. My point is not that we should be constructing longhouses in the hearts of our cities, but rather that, in designing our cities, we should embrace the idea of the longhouse in our hearts: the idea that what we are really building is a community, where individuals and families can thrive, and where people feel connected to each other and to the natural environment – all part of the sacred circle of life.

Let us ensure urban architecture enables people to engage with, learn from and support one another.

That is how we can build for belonging, and build cities we are proud to call home.

The unseen pain

Human beings are social creatures. From the moment we are born, we crave the touch and attention of others. We need those things to survive. And when human connections are absent or lost, we suffer physically, emotionally and spiritually. Social isolation correlates to afflictions from depression to heart disease to early death.

Almost by definition, the pain of social isolation too often goes unseen. Yet it exists all around us: among people with physical or intellectual disabilities, too often excluded from society’s mainstream; among elderly people, such as in the UK where nearly half of all older people say their primary form of company is the television or their pets; among those who are economically disadvantaged or displaced by the harsh winds of our volatile world; among marginalised populations who for reasons of community or caste are locked outside all circles of concern.

There is much we can do to repair and renew the fabric of belonging, and to build resilience among individuals and across entire societies. It matters to all of us, because the bonds of belonging run in both directions. In extending a hand to someone else, it is we who are touched as well.

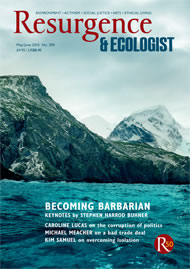

Kim Samuel is Professor of Practice at McGill University’s Institute for Studies in International Development, and Policy Advisor to the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative, where her work focuses on social isolation and multidimensional poverty. She is also a member of the Resurgence Trust board of trustees.