A chance glance at a map pulled Rob Cowen into a prolonged love affair with a liminal area near his house in Bilton, North Yorkshire: a patch covering just half a square mile, it borders a sewage farm and embraces fields, woods, a disused railway viaduct, pylons and much brambled detritus. It turns out to be teeming with wildlife, too, encouraged by human neglect and a small river, the Nidd.

There is nothing new about odes to edgelands – Dickens relished describing them as 19th-century London gnawed ever further out – and the author indicates his literary debts – Paul Farley and Michael Symmons Roberts’ Edgelands similarly includes the “dark dials” of sewage ponds – but Common Ground is also the record of obsession, loneliness and anxiety. Dreaming of liberation from the city, Cowen returned to his childhood county while his wife temporarily stayed behind in London, but “moving house had proved to be an imprisonment.” Thus the scrap on the map became a refuge and a healing space: “It has begun to colonise my sleeping mind.”

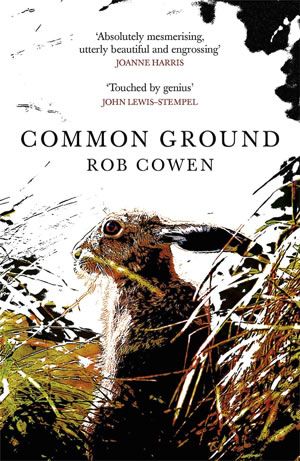

Cowen in turn spiritually colonises its wildlife – dramatic creatures such as owls and foxes and hares, each with an air of mystery and magic; or ungraspable entities like swifts, as well as modest ladybirds and butterflies. (He knows his flora, too.) He tracks them through snow, rain, nettles and thorns, wanting to join “an earlier world”, its “sheer immediacy”. The fox is particularly resonant for him. There is a long bravura section when he thinks himself into its famished consciousness, all the way to its agonising death in a trap. There’s a danger in anthropomorphic writing, of course: the colonisation of something completely other; I was less convinced by the first-person (sic) account of a hunted deer. However, Cowen’s skill translates the fox’s existence into something like a shamanic dance: there is a real shock when, in human guise again, he finds the corpse: “That flame fur has long since leached into the earth.”

Foxes are our suburban familiars now, of course, but with a startling otherness. Owls are something else, not cute or wise, but ruthless hunters. Cowen is reminded of this when, visiting Harrogate’s antenatal clinic, he sees a child’s drawing of a tawny owl Blu-Tacked on the noticeboard; feeling his wife Rosie’s bump, he senses the vulnerability of humankind. Looking out at “the lone oak, the razor-cut line of hills, the pylons, the smothered steeples, domes and towers of town”, he recognises how easily things can go wrong. Rosie’s pregnancy provides a strong philosophical and narrative pull to the seasonal cycle of note-taking and solitary discoveries, revelations and epiphanies continuing through the seasons, culminating in a gripping scene that had me wiping my eyes.

Thus Cowen’s naturalist expertise is interwoven with his own personal doubts and fears, and is admirably tuned into the subjective malleability of the countryside, being ultimately a projection of his own altering states. Not so much what he sees, but who he is when he sees it. A glimpsed tramp, ‘Sir Hare’ – if more like a fox in his prowling opportunism, secreted by his fire in the Bilton woods – holds forth in a long, imagined monologue: a former Sixties adman turned guerrilla ecologist, he allows Cowen to vent his political spleen as well illuminating some of his deeper sources: “I fell into the rituals of earlier times. I prayed to the gods of Celt, Saxon, Angle and Jute and communed with the insects, animals and plants seeking to learn the secrets of their microbial, cellular majesty.”

Apart from this passion for burrowing in and dissolving the species’ borders, Cowen takes us through the area’s history from the Mesolithic hunters on, dwelling particularly on the last 300 years: the enclosures, the appropriations by the rich, the loss of the peasantry, the conversion of land into profit, the triumph of self-interest, the land’s chemical soakings, its inevitable disappearance under new estates. This is mostly done through footfall, including the discovery of the capstone laid long ago over a possible sulphur spring: ownership, “a new departure in our changing relationship with land”.

There are marvellously lyrical passages on swifts and mayflies, on the modest history of a single buddleia bush, on the sting of nettles and on the lost son of Bilton Hall, a revenant from the trenches. Cowen’s relationship with this morsel of land is intense and honest, and described in superb prose. I travelled the lanes around it on Google Street View, and glimpsed English-pretty northern countryside. A “wilful trespasser”, Cowen has turned it all into something not only rich and strange, but also astonishing.