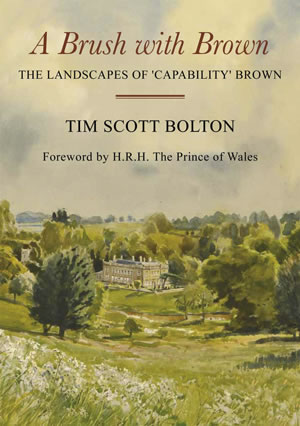

For the last two years I have been visiting and painting Lancelot Brown’s landscapes and gathering information for my first book, A Brush with Brown. The scope of what Brown achieved is enormous, for not only did he create our enduring vision of the typical English park with clumps of trees and a lake, but he also built great houses, roads, follies and industrial-scale kitchen gardens.

As a boy I was lucky to have an older brother who was an enthusiastic naturalist. In those carefree days 60 years ago we used to cycle off and collect snakes and lizards and even whole wood-ant nests, which we used to bundle into big sweet jars and nurture in an old greenhouse allocated to us by my long-suffering father. Continental journeys with my parents became a wildlife-collecting rampage, and at my prep school I was even caught with a tin in my tuck box full of scorpions collected in Italy.

I soon realised with my naturalist’s eye that due to Brown’s enthusiasm for the ‘natural’ landscape a great number of ecologically important places have been conserved for us today. In the early 18th century, large houses would have been surrounded by elaborate and extensive formal gardens, Dutch in style and promoted by William of Orange. The leading designers of the time were George London and Henry Wise. Now nearly all their gardens are no more, swept away later in the century by the fashion for the natural garden promoted first by William Kent and later by ‘Capability’ Brown, who worked under Kent at Stowe.

This new vision of beauty was inspired by the paintings of Nicholas Poussin and Claude Lorrain, among others, brought back by the great landowners as spoils of the grand tour. They showed a romanticised form of Nature with woods, dales, ruined classical buildings and gushing rivers or lakes reflecting the evening light. This is what the aspiring plutocrat wanted his parks to be like.

The slow process of growth, decay and regeneration has taken place over the 250 interceding years, and now many parks thus created have become important islands of Nature in a desert of intensive agriculture. Because of the scale of Brown’s ambitious schemes, many form their own extensive ecosystems – in contrast to most nature reserves and SSSIs often created for the limited scope of preserving one species.

Brown originally made his name as a water engineer, and lakes and alterations to rivers are always an important feature of his ‘gardens’. Much of our landscape has now been drained, and remaining bodies of water have become increasingly important for every form of wildlife.

The aquatic food chain is totally dependent on the health of microorganisms such as daphnia and a whole host of protozoa so often destroyed by insecticides sprayed on much arable land. Many of the great parks have extensive enough grassland to protect the water against this.

‘Capability’ Brown should be made patron saint of fishing. Nearly every lake I visited had its enthusiastic fishing club. Both coarse fish such as pike, carp, chub and dace and their smaller cousins stickleback and minnow inhabit the stiller bodies of water, while those fed by fast-flowing rivers are home to brown trout.

Of much more importance to the artist, however, are the birds and mammals. The long stationary hours I spend painting mean that I become part of the landscape and soon am ignored by the various feathered and furry inhabitants thereabouts. A raft of ducks will drift closer, or a great crested grebe will dive and resurface in the reeds nearby. The inclusion of these will enliven a landscape with a dash of white or a ripple, and a flock of flying geese will give a sense of scale and space to a picture with the great sky beyond.

A frosty morning at Petworth, and some fine old chestnuts stand out against the sky; it is a perfect day for painting, and just at the right time a group of fallow deer, of the same stock that Turner painted here 200 years ago, drift into my view. The grass has been left tussocky, and large old branches from the venerable trees lie around to decay and provide a perfect habitat for stag beetles. The National Trust, the owners of this Brown landscape, are exemplary ecological guardians. In this context I was particularly impressed by the work at another of their properties, Wimpole Hall near Cambridge, where they are conserving rare breeds of livestock within the fine park and at the home farm. Here I painted Longhorn and the English white cattle, in appearance much like the famous Chillingham cattle in Northumberland.

Many private owners of Browns parks also play their part in conservation. Perhaps the most important of these within the London area is at Syon, which belongs to the Duke of Northumberland. Its long unbroken history as parkland has created a habitat of rich diversity, which includes more than 140 species of fungus and 50 species of lichen. The old trees, many pre-Brown, provide habitat for bats. The unique feature, however, is that, being within the tidal area, this reach of the Thames has the only significant stretch of natural riverbank, meaning that it floods twice a day at high tide.

Another estate Brown landscaped is at Southill in Bedfordshire, where the current owner, Charles Whitbread, is extensively farming with conservation in mind. Wild bird mixes in his crops and encouragement of the insect population have among other things rejuvenated the numbers of grey partridge.

Walled gardens, whether being maintained or in decay, are another habitat for a wide variety of plants and animals. Lord Bute at Luton Hoo was partly responsible for the establishment of the National Plant Collection at Kew. In his walled garden he grew plants from seed from all over the world and meticulously recorded them. In their heroic restoration of these extensive gardens, which had largely become derelict, the Phillips family have recreated some of Lord Bute’s plantings.

It is the unexpected byways of exploration (both physical and academic) that have given me so much pleasure in my Brownian ramblings. I approach my book from the point of view of a landscape painter, and this has freed me to muse on any topic I fancied at the 43 properties I visited. I hope the fun I had painting and writing is conveyed in my book about ‘Capability’ Brown.