Ganga, whose waves in Swarga flow,

Is daughter of the Lord of Snow.

Win Shiva, that his aid be lent

To hold her in her mid-descent.

For earth alone will never bear

Those torrents hurled from upper air.

The Ramayana, Book I, Canto XLIII: Bhagirath

Treks to the source of the Ganges are among my fondest memories of childhood. At an altitude of 3,100 metres stands the Gangotri, where a temple is dedicated to Mother Ganga, who is worshipped as both a sacred river and a goddess. A few steps from the Ganga temple is the Bhagirath Shila, a stone upon which King Bhagirath supposedly meditated to bring the Ganges to the earth. The shrine opens every year on Akshaya Tritiye, which falls during the last week of April or the first week of May. On this day, farmers prepare to plant their new seeds. The Ganga temple closes on the day of the Deepavali, the festival of lights, and the shrine of the goddess Ganga is then taken to Haridwar, Prayag and Varanasi.

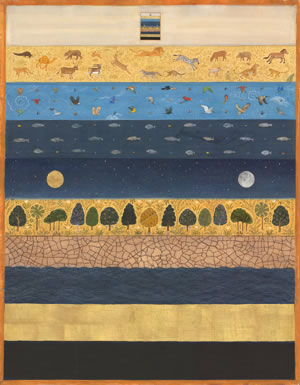

The story of the descent of the Ganges is an ecological story. The above hymn is a tale of the hydrological problems associated with the descent of a mighty river like the Ganges. H.C. Reiger, the eminent Himalayan ecologist, described the material rationality of the hymn in the following words: “In the scriptures a realization is there that if all the waters which descend upon the mountain were to beat down upon the naked earth, then earth would never bear the torrents… In Shiva’s hair we have a very well-known physical device, which breaks the force of the water coming down … the vegetation of the mountains.” The Ganges is not just a giver of peace after death: she is also a source of prosperity in life. She is the source of energy – ecological, cosmological, economic, social and cultural energy – for the people of India.

In today’s dominant paradigm however, ‘energy’ refers to oil and coal, which are mined from the earth, shipped thousands of miles, and transformed into electricity to light up neon signs or into fuel to run SUVs. It is fruitful to remember that energy has other meanings and other forms: from shakti, the generative force of the universe, to the sun that powers our lives, to the water that comes to us as bountiful rain or a flood or a tsunami, or trickling and then roaring from Gangotri to fuel a living universe, to the air and the wind that move the clouds and create the climate. Energy is not just oil and coal and gas. Energy is an all-pervasive element of life.

The broader our paradigm of energy, the wider our choices as human beings. Fossil fuels have fossilised our imagination, our potential, our creativity, our wildness. We need to break free from this fossilisation to choose life-enhancing pathways for ourselves, our species and the planet.

The mechanistic paradigm has robbed us of our freedom and creativity. It has replaced living energy with fossil fuels; the wealth created by Nature with that created by people with capital; the freedom of citizens and communities with the coercive power of the corporate state that imposes the rule of capital in every dimension of our life – the thoughts we think, the food we eat, the settlements we shape.

In this life-threatening period of globalisation and climate crisis, we need to unleash our hidden energies to make a transition to a post-fossil-fuel economy. To do so, we need to reinvent democracy. A renewable-energy economy will only be built through the renewable energy of free and self-organised citizens and communities. The transition beyond oil is not merely a technological transition: it is above all a political transition in which we stop being passive and become active agents of transformation by recognising that we have the capacity, the energy and the creativity to make the change.

Life is based on the self-organising energies of the universe, from cells to Gaia, from communities to countries. We as living systems are networks of chemical and energetic flow and transformation. Thus life is energy – not fossil fuel energy, but living energy.

Does this kind of renewal, this kind of self-organising energy, speak to my view of wildness? Cartesian dualism and the colonising worldview left us with a legacy that defined the wild as free of humans, and the cultivated as free of Nature. On the one hand, this led to the extermination of all that was considered wild in the colonised and settled zones, from the bison to native people. It created an industrial agricultural model based on designing violent tools to exterminate biodiversity and everything alive – from the chemical fertilisers that kill the soil organisms that feed us, to the pesticides that kill the friendly insects (including bees and butterflies that help produce a third of our food), to the herbicides that kill plants that are food for humans and other species.

On the other hand, it created a paradigm of wildlife conservation and national parks based on driving out the people who had conserved those places and their biodiversity. India is riddled with conflicts between people and parks because of this artificial legacy of the humanless wild, which becomes an inhuman construction of the wild. For the last four decades, I have worked to bridge this artificial divide by cultivating the wild.

The self-organisation of life is, for me, the definition of being wild. We save and conserve seeds because in their self-organisation lies their wildness. We engage in participatory breeding as the co-creative co-evolution between intelligent seeds and intelligent peasants. When we cultivate biodiversity as navdanya (nine seeds) or baranaja (twelve seeds), we are cultivating the wild in terms of the self-organised cooperation not just among different plants, but also between the plants and soil organisms, between plants and pollinators, and among the community of insects, including those that control pests without pesticides and GMOs.

By trusting the wild, we grow more food than is produced through the use of violent tools and the violent attempt to “feed the world” by attempting to kill the wild. We have 350% more nitrogen in our soils than farms that use synthetic nitrogen fertilisers. We have six times more pollinators than in the forest next door.

Food grown through cultivating the wild is also healthier. Toxic pesticides and GMOs are not just killing the wild outside: they are also killing the wildness we need in our gut biome for our health. It is claimed that such pesticides and crops are safe for humans because, unlike the metabolic routes of bacteria, fungi, algae and plants, humans do not have the shikimate pathway. Yet some 90% of the genetic information in our body is not human, but bacterial.

Out of the 600 trillion cells in our body, only 6 trillion are human: the rest are bacterial. And bacteria have the shikimate pathway. The bacteria in our gut are being killed by pesticides, leading to serious disease epidemics, from increasing intestinal disorders to possible neurological problems such as increases in the occurrence of autism and Alzheimer’s. The soil, the gut and the brain are one interconnected biome. Violence to one part triggers violence in the entire interrelated system.

Data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show alarming trends related to the percentage of children born with some form of autism in the United States. An intelligent species does not destroy its own future because of a distorted and manipulated definition of science. Einstein is said to have observed, “Two things are infinite: the universe and human stupidity… and I’m not so sure about the universe.”

When I talk about the infinite creative energy of the universe, I am talking about Gaia’s self-organising energy, the creative human energy to work and to produce, to organise, and to transform. In India and around the world, this human energy has helped cultivate the self-organising energy (whether a culture calls it shakti or wildness) of the world. In particular, the creativity, innovation and decision-making power of women (who still produce 80% of the world’s food) have significantly driven the world’s biodiversity. The majority of the 80,000 plant species that humans have cultivated have emerged from the self-organising, living energies of women. In other words, if we are going to redefine wildness, we have to simultaneously redefine humans as co-creators of wealth with Nature. We both rely on and co-create wildness when our living energies work with those of the earth.

Beyond Gangotri lies Gaumukh, a glacier formed like the snout of a cow, which gives rise to the Ganges. Twenty-four kilometres in length and 6 to 8 kilometres in width, the glacier is receding at a rate of 5 metres per year. The receding glacier of the Ganges, the lifeline for millions of people in the Gangetic plain, has serious consequences for the future of India. We need to generate and multiply the renewable energy of ecology and sharing, of solidarity and compassion, to counter the destructive energy of greed that is creating scarcity at every level: scarcity of work, scarcity of happiness, scarcity of security, scarcity of freedom, and even scarcity of the future.

Either we can let the process of destruction, disintegration and extermination continue unchallenged, or we can unleash our creative and wild energies to make systemic change and reclaim our future as a species, as part of the Earth family. We can either keep sleepwalking to extinction, or wake up to the potential of the planet and ourselves.

This is an edited version of an article reprinted with permission from Wildness: Relations of People and Place, edited by Gavin Van Horn and John Hausdoerffer, published by The University of Chicago Press. © 2017 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Resurgence & Ecologist readers can buy this book for £18 – a 20% discount on the paperback price. Go to tinyurl.com/ucp-wildness and use the code 44483.