Just for a moment, forget the latest twist in Brexit and the last tweet of Trump, and scan the far horizon of the 21st century. By 2100, more than 10 billion people will be living on Earth, all seeking to lead lives of dignity and opportunity. As we head towards that future, can we discover how to thrive together?

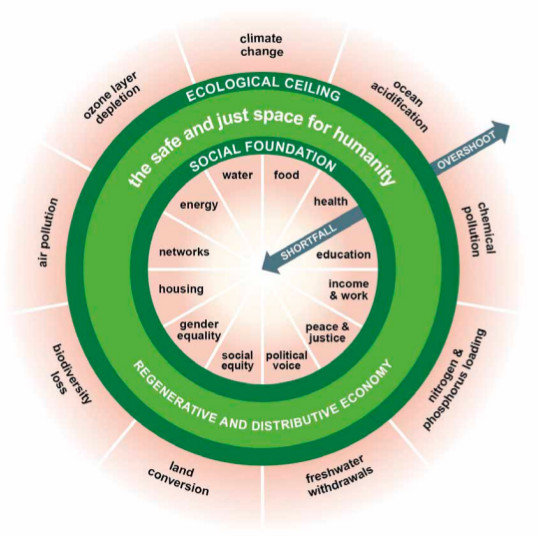

I believe the answer can be yes, but only if we first understand what it takes for humanity to thrive. It means meeting every person’s needs so that no one is left falling short on life’s essentials, from food, housing and healthcare to energy, education and political voice. But it simultaneously depends upon safeguarding Earth’s critical life-supporting systems that underpin our collective wellbeing, from a stable climate and healthy oceans to abundant biodiversity, fertile soils and a protective ozone layer. In other words, we need to get into the Doughnut, the safe and just space in which all of humanity can thrive.

The Doughnut: a safe and just space for humanity. Image credit: Kate Raworth and Christian Guthier / The Lancet Planetary Health

If we are collectively smart in the way we go about it, we can indeed meet the needs of all within the means of the planet. But it will take a transformative redesign of our economies. The 20th century bequeathed us with economies that need to grow, whether or not they make us thrive, and we are living through the social and ecological fallout of that inheritance. The 21st century presents us with a challenge – or perhaps an opportunity – that our predecessors didn’t have to contemplate: to create economies that make us thrive, whether or not they grow. It sounds like a simple flip of words, perhaps, but it’s a radical flip in perspective on the future of economic growth.

In today’s low-income countries such as Ethiopia and Cambodia, GDP or gross domestic product – the total monetary value of products and services sold in a nation’s economy – is growing fast, at 7–10% per year. Invested wisely, that growth tends to come hand in hand with crucial gains in human wellbeing, ranging from longer, healthier lives to more children in school, as households and the state alike have more resources for investing in improving the essentials of life. In such countries future GDP growth is very likely coming and is very much needed.

It is in today’s high-income countries, however, that the tricky questions arise because GDP growth has been stalling. The club of high-income countries known as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) was set up in 1961 with the aim of pursuing the highest sustainable economic growth, but the average annual growth rate of 13 of its founding countries fell from over 5% in the early 1960s to under 2% by 2011, now hitting near-zero in some. To complicate matters, this slow growth has been accompanied by severe ecological overshoot, with many OECD countries requiring the equivalent of four or more planet Earths to sustain their current lifestyles. What’s more, slower growth has been accompanied by widening income inequalities, with the gap between rich and poor in most OECD countries at its highest level in 30 years.

If questioning endless GDP growth once seemed to be the terrain of radicals, it has now gone mainstream: while some have long doubted that growth could be made environmentally sustainable, others now question whether growth is coming at all. The OECD has forecast “flat” growth for many member countries over coming decades, while according to Larry Summers, a former World Bank chief economist, we have entered “the age of secular stagnation”.

So does this mean it is simply time for high-income countries to prepare for a future of low or zero GDP growth? Not at all: if humanity is to flourish in the 21st century, these economies need to undergo a profound transformation – and one that entails a far more radical growth rethink.

Thanks to the inheritance of 20th-century economic design, today’s high-income economies are degenerative and divisive by default. They are degenerative thanks to their dependence on industrial processes that take Earth’s materials, make them into stuff we want, use for a while, and then toss away. This linear process of take-make-use-lose cuts against the cyclical processes of life, driving us to devour the sources of our own sustenance and run down Earth’s life-supporting systems, on which we depend.

These economies have simultaneously become divisive by default, due to the concentration of wealth. Thanks to current ownership structures of business and finance, of land and housing, and of ideas and technology, the vast share of gains from GDP growth is typically captured by the already well-off, leaving near-stagnant incomes for the majority.

If humanity is to have half a chance of meeting the needs of all within the means of the planet this century, tomorrow’s economies must be regenerative and distributive by design. That calls for cradle-to-cradle industrial design that restores humanity as a full participant in regenerating Earth’s cyclical processes of life. And it calls for pre-distributing the diverse sources of wealth, so that value created is shared far more equitably amongst all who help to create it.

Such ambitious redesign calls for many economic transformations. Like what? Like switching energy generation from fossil fuels to renewables. Swapping private car ownership for shared access to rental cars and public transport. Setting up enterprises that are owned by their employees and dedicated investors, rather than by distant and fickle shareholders. Creating complementary currencies that empower local communities instead of leaving money creation as a matter for commercial banks. Launching innovative technologies, not with patents and copyright, but under creative commons licensing that permits ideas to be used and improved endlessly. Redesigning investment finance, both public and private, so that it is in service to society’s long-term collective interests.

In the process of such an extraordinary transition, what might happen to the size of GDP – that total value of goods and services bought and sold? Despite the convictions of many mainstream economists, it is by no means obvious that GDP could or would endlessly increase. It may need to rise at first, as new energy and transport infrastructure is built. It may come to flatline, even fall. Or it could end up oscillating around a steady level. In short, GDP needs to shift from being – in the jargon of economists – a target metric for growth to becoming a response variable that adapts and adjusts to the process of creating a regenerative and distributive economy.

It may make sense, but this is precisely why we have a problem: over the past two centuries, the laws, institutions, policies and cultures of today’s industrial economies have been structured to expect, demand and depend upon an ever-rising GDP. Our economies, in other words, are financially, politically and socially addicted to growth.

Stand back a moment and reflect on just how out of kilter with the living world this is. In Nature, growth is a healthy phase of life, but it is only that: a phase. From our children’s feet or an apple tree to the Amazon forest itself, nothing in Nature grows forever: at some point, it matures, comes to thrive at full size, and in doing so can thrive for a very long time. Indeed something that tries to grow forever may well destroy the system on which it depends – and in our own bodies we call that cancer. It is striking, then, that mainstream economists assume without question that endless GDP growth is both possible and desirable. And that unquestioning assumption is, I believe, thanks to our addiction to economic growth.

The financial addiction arises from what the economic historian Karl Polanyi called the search for “gain” at the heart of the financial system. It is visible today in the corporate culture of shareholder primacy, which drives perpetual expansion, and in the power granted to commercial banks to create money as interest-bearing debt, thus requiring more money to repay it. As the regenerative economic thinker John Fullerton says, “we have reached the logical conclusion of this expansionist economic paradigm. Unless we can achieve magical decoupling we have an exponential function on a closed system planet … yet the finance system has no inbuilt plateau, it can’t ‘mature’ – and none of the experts in finance are even thinking about this.”

The political addiction to growth, in turn, arises from the hope, fear and pride of governments. They hope to increase tax revenues without raising tax rates, and to do that you need a growing GDP. They have an understandable fear of the unemployment line, which all too quickly emerges when GDP stagnates – and growth has long been proffered as the solution for that. And governments take great pride in their geopolitical place in the world. No prime minister, president or chancellor wants to lose his or her place in the G20 family photograph, that portrait of leaders taken at the annual get-together of the world’s most powerful economies. For their leaders to stay in that picture, every nation must keep growing its GDP, or it will soon be ousted from the frame by the next emerging-economy powerhouse.

Lastly, the social addiction to growth is thanks to a century of consumerism. Far richer than kings of old, we are too easily trapped on a treadmill of consumerism, convinced that we will find identity, connection and status by buying something more. What will it take to enable us to shake off this addiction, so that society no longer believes that the best form of therapy is retail therapy? “Wherever and whenever we are excessive in our lives it is the sign of an as yet unknown deprivation,” writes the psychoanalyst Adam Phillips. “Our excesses are the best clue we have to our own poverty, and our best way of concealing it from ourselves.” When it comes to consumerism, perhaps the poverty that we aim to conceal lies in our neglected relationships with each other and the living world.

So are these financial, political and social addictions to unending GDP growth insurmountable? Not one of them, but today far too few economists are focused on exploring ways to overcome them. It’s time for that to change. For a thriving future we need economies that are regenerative and distributive by design. That means creating economies that enable us to thrive, whether or not they grow. It’s time to overcome the addiction to ever-rising GDP and become agnostic about growth. For the aspiring 21st-century economist, that’s a task well worth taking on.