One day in 1997, I was sitting in a pub in south-west London, discussing with a friend how constricted and relatively inward-looking were the routes to getting poetry published. Hundreds of poems are submitted every week to busy little poetry magazines. But who reads them? The world of contemporary poetry is actually rather small. And what is poetry for, anyway?

At the time, I was a mental health social work manager. My friend, Paul, was a community psychiatric nurse who also offered counselling sessions in doctors’ surgeries. It was he who suddenly saw a meaningful place for poetry in waiting space and time. We both knew what lonely places waiting rooms can be, even when full of patients. Here was a different form of publication, a different kind of audience, and almost a different language for poetry to speak in.

We put some leaflets together (mostly of my own poetry). Then another friend suggested the material we published should not just be my own. (I was mortified!) I came up with our first title “Poems for the Waiting Room”, and we started to get very excited – I was realising what an opening we had stumbled into.

Everyone sits in the waiting room at some time or other. It is one of the most democratic public settings in the world. Our humanity is shared in this place, through our common fragilities. And perhaps here we are more in touch with what matters than in most other places. Poetry belongs here, perhaps on the walls, far more than in some literary magazine. Here it can speak out and reach out.

At the time, the Labour Party had just come to power in Britain, and more money was being given for the arts. A particular Arts Council funding source had just been set up – very New Labour – called New Audiences. Someone suggested I contact the Poetry Society, so I rang its newish director, Chris Meade, an ex-librarian. By coincidence, Chris had his own ideas for democratising poetry beyond the specialist bookshops and literary clubs. He was calling it “Poetry Places” and was presently applying for funding for it from the National Lottery. Without even waiting to meet me, he added the healthcare waiting room to his list of possible places for poetry and suggested we apply for the funding together.

And that is how we were able to pilot the idea of distributing small posters carrying poetry in doctors’ waiting rooms around south-west London, under the Poetry Society’s supervision. A year later the pilot was featured in a Guardian article and we applied (successfully) to the Arts Council for follow-up funding under its New Audiences scheme. Since then, the project has spread far beyond, with funding over the years from the Arts Council, the King’s Fund, the NHS, the Baring Foundation, the Mayor of London, the John Lewis Partnership and the Foreign Office.

There are presently three main collections available. The first is called “Poems for… Waiting” and consists of 50 poems, each one about waiting, each especially commissioned by the Birmingham poet David Hart.

The second collection is called “Poems for… All Ages” and consists of another 50 poems, many gleaned from that wonderful anthology edited by Ted Hughes and Seamus Heaney called The Rattle Bag. Also in the “All Ages” collection are a dozen poems for young children. The selection was put together mainly with the healthcare waiting room still in mind.

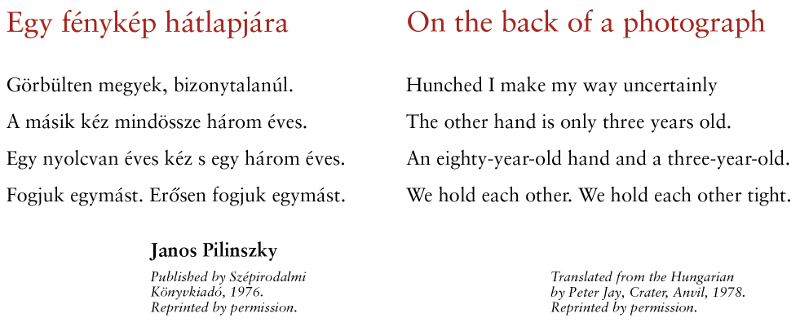

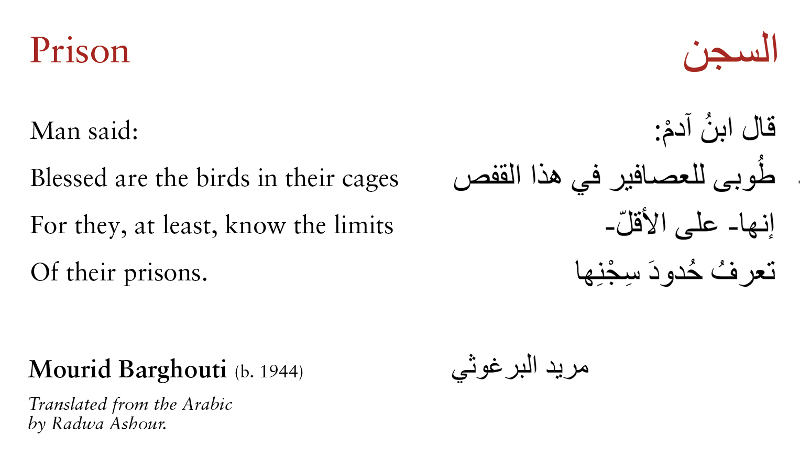

The third, latest and largest collection consists of over 100 poems, the great majority of which are bilingual. In that collection, called “Poems for… One World”, 50 different languages are now represented. Many of the authors are internationally famous. After Andrew Motion, Poet Laureate of the time, had launched the first tranche of the bilingual collection in 2005, David Hart wrote to me. “We have a chance here to open people’s lives to each other,” he said.

Published by The Poetry Trust in “A Small Sun” 2003. Reprinted by permission. Mourid Barghouti is a Palestinian poet.

Soon the bilingual collection attracted some publicity, and schools began ordering the packs of bilingual poems. A few months later, we changed the project’s overall title from “Poems for the Waiting Room” to “Poems for…” Now it is simply “Poems for… the Wall”.

In 2008, Andrew Motion launched our new website for us in the Nehru Centre in London. Now we no longer keep the poems in hard copy, printed commercially. Instead, all the poems we have available can be downloaded direct from our website, all free of charge. They still go mostly to schools (but also to libraries and still to healthcare settings) but now it is to schools, libraries and healthcare settings all over the world. More recently, I worked with the charity United Response to add two new groupings to the “Poems for… One World” collection – 30 poems on mental ill health, and 20 on learning disability. I believe they belong in schools as part of an anti-stigma teaching package.

Does this project really “open people’s lives to each other”? Can it stop walls going up, the fears, the nationalistic barricades, the urge to exclude and expel and “take back control” in so much of our present ugly political discourse? It has not, of course. But that is no reason for these poems to stop appearing. They justify and speak very well for themselves. What is the bilingual collection saying? Surely, that connection across difference adds to our lives, is even essential, integral to being civilised.