After a morning of intense classroom discussion, we met outside, bundled against the cold, ready for a walk in nearby woodland. The way up from the retreat centre took us along the road, where damp sycamore leaves, yellowy green, stuck soggily to the ground, and my stick clicked against the hard surface with each stride. Through gaps between the trees we could see down the hill to the floodplain of Strathspey and the snow-covered Cairngorms beyond. In the bright November sunlight the details on the trees stood out: the patterns of the bark, the growth of fuzzy lichen, the tracery of bare branches against the sky.

A little way up the hill, we followed a track off to the left, squelching our way through thick black mud full of humus and dark wetness. Then we turned again, through a galvanised farm gate stuck open just wide enough for walkers, and crossed a patch of rough grassland into a stand of Scots pine marching up the rise ahead.

As soon as we were amongst the trees I felt a completely different quality of space. From house to road, road to muddy track, track to rough grassland: that was three transitions already on this short walk. Now I felt another, an uncanny shift, a feeling of leaving the everyday behind and moving into… Into what? What was it that made me at that moment mutter a prayer to remind me of my interconnectedness – “to all my relations” – as I might when walking into a stone circle, crawling into a sweat lodge, or entering an ancient church?

I am hard put to say what this shift consists of, but as I stepped beneath the trees I felt I was taking a further step away from the classroom, the road, even the mud, into an opening, a spaciousness, a place of greater calm. Maybe it was simply an intuitive sense of stepping into an ecological niche that was self-regulating with little interference from human beings. Maybe it was more than this. Maybe I might even dare the word ‘sacred’.

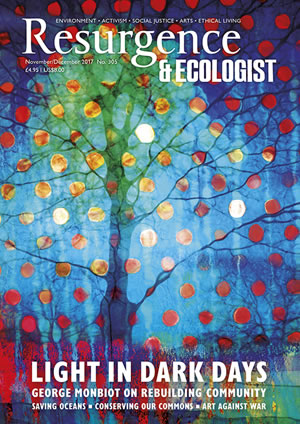

We walked deeper into the woodland, weaving our way between the upright pines, breathing harder as we pushed up the slope. Ahead, I saw the hint of a darker form, a contrasting shape: an ancient oak, maybe three hundred years old – it must have been a mature tree long before the pines were planted. The huge trunk was covered in great gnarled burrs, patterned with green-grey moss and lichen. Its limbs branched out in all directions, crossing over each other to make strange patterns; all had died back towards the ends; some were completely dead. This season’s leaves still clung to the living branches, fading from green to bronze. Piles of old leaves in various stages of decay clustered in the forks.

We sat together round the base of the trunk, drawing, writing or just sitting quietly, taking in the presence of this strange old being, and then continued on our walk. As we left the canopy of trees, I turned and looked back at the gaunt shape of the oak, its tangled structure contrasting so clearly with the verticality of the pines, and placed it firmly in my memory. Days later, as the train rocketed on the long journey home to the south of England, the image of the tree came back to me. As I rushed southward, it was standing there, its old rotten branches reaching out, leaves turning and gradually falling, all on its own amongst the pines.