When the retailer and broadcaster Mary Portas led a government-appointed review into the future of the British high street in 2011, her findings were that it was heading for extinction.

While it probably wouldn’t have come as a surprise to most Resurgence & Ecologist readers, the woman dubbed ‘Queen of Shops’ proclaimed that out-of-town retail, shopping malls, supermarkets and the internet had created a crisis for small shops and retailers.

“The days of a high street populated simply by independent butchers, bakers and candlestick makers are, except in the most exceptional circumstances, over,” Portas stated, provocatively.

By early 2017 things appeared even bleaker. David Jinks, head of consumer research at the distribution company ParcelHero, released a report, 2030: Dead End for the High Street, which stated that unless retailers, councils and planning authorities take action, half of the UK’s shop premises will disappear by 2030 due to competition from e-commerce and home delivery companies. Online spending currently accounts for 15.2% of all UK retail sales, but is forecast to reach 40% by 2030.

Yet I happen to drop into Ilminster, a historic market town in Somerset, and it defies these apocalyptic predictions. I find small shops flourishing and not one boarded-up shopfront. Locals tell me outsiders are jealous of the town, and the shops co-exist happily with a Tesco superstore. So, what is the secret?

I pop into the pet shop, and whilst it has bird food, cat treats, rabbit hutches, fish flakes and dog baskets, it also sells, amongst other things, nuts, bolts, screws, puzzles, toys, fishing rods, christening gifts, chocolate, cakes, batteries, garden ornaments, crayons, tea bags, bin liners and collectible model cars.

“It’s like an Aladdin’s cave,” says a customer buying green beans. There is no pet food in her purchase. “If he just sold pet food, he wouldn’t survive. You come in for one thing and you buy something else,” she adds.

“A lot of people shop online now – you see the vans pulling up,” says Brian Drury, 70, who has run BD Garden & Pet Supplies since the 1980s. “You’ve got to sell all this stuff to keep going.” He adds that he decided to increase his product lines when Tesco arrived in the town 15 years ago. “I didn’t think you could keep going with just one line. We want to attract the younger generation, so it’s anything to pull them in,” he says.

But don’t the customers get confused, as they don’t know what shop they’re entering?

“No, they’re used to it in Ilminster.”

As is the intention with Transition Towns, I discover, local businesses in Ilminster go out of their way to support each other.

“The local vets buy pet food from us and try to support us,” says Drury.

I wander into The Ilminster Bookshop, expecting to buy, well, books. And while they do have an array of titles on sale, bottles of Pinot Noir from Bourgogne, Gewürztraminer from Alsace, other wines, cider and beers are lined up on the shelves alongside. Ileana Nguyen explains: “We did think of putting a café inside, but we didn’t want to compete with the coffee shop. Then we decided on wine, as the local vintners had recently closed down. There’s an etiquette involved, so we didn’t want to start selling cheese, as there’s a dairy shop nearby. But in the wind it’s the tree with the most roots that stands,” adds the 40-year-old, who runs the shop with her husband, Drew.

They sell wine from local independent suppliers, and the local hair salon cracks open their bottles when it has late nights. They are now planning events with a professional wine taster. “We’re going to work with the cricket club and offer wine tasting at garden parties,” Nguyen says. “We need to get online too.”

I spot the wool shop next. Whilst there are bundles of wool inside, there are also greetings cards, wrapping paper, shoes, socks and other clothes, toys and scouring pads.

So was there some coordination of this diversification strategy? According to Phillip Wyatt, the president of Ilminster Chamber of Commerce, the shopkeepers have all diversified spontaneously. “There’s been no plan set out at all. I guess the shopkeepers might hear a customer wants something, and they pick up on things the town doesn’t do and start selling them.”

“In the face of mounting pressures, small businesses and independent retailers are constantly having to diversify in order to grow,” says Mike Cherry, National Chairman of the Federation of Small Businesses (FSB). “This is particularly pertinent for those in the retail sector, which, due to their reliance on property, has seen many hit by increases in business rates as well as rising rents.”

Cherry adds that small retailers are hugely important to the local economy. FSB research shows that for every £1 spent with a small or medium-size business, 63p is respent in the local area compared to 40p in every £1 spent with a chain or larger business.

“I love the fact the shops are so diversified,” says Corrin Garland, 45, who has lived in the town of 6,000 residents for 11 years, “because you have more chance to get what you want. I think it’s good you can go into the wool shop and get a birthday card or clothes.”

Next I venture into recycled and upcycled interior shop The Green House. Opposite the lampshades made from colanders, and clocks made from skateboards is a gluten-free café.

Martha Vickery, 21, the daughter of the shop owners, explains: “People used to come in and either they were a bit shell-shocked by what we sold and walked out, or they stayed for two hours. The fact we have a café means people can come in and appreciate what we do. It’s symbiotic – both help each other and they work better as a whole. Mum and Dad want it to be a community hub,” she says, pointing to a piano left for anyone to play on.

Margaret Pollain, 84, is in the café. “Tesco caters for families. I don’t want a big bag of oranges, so for groceries I go to the small shops,” she says. “A lot of people round here don’t use Tesco, to help keep the smaller shops going.

“We have the most marvellous butcher,” she adds. “You can even ask them how to cook something. They chat to you and know your face. If you didn’t have transport you could do all your shopping here. The shops have to sell as much as possible as rents are so high.”

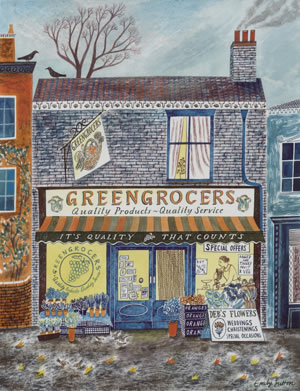

I pop over to the greengrocer’s – and by now I’m not surprised to find silver jewellery and not marrows on display in the window. Alongside carrots, watercress, nectarines, blackberries, runner beans and the like are ribbons, knitted elephants, locally produced tea and coffee, apple juice and biscuits. “People like the variety and it brings in extra customers,” says Mike Adams, 44, who has run the business for nine years.

“Fruit and veg are our mainstay, but it doesn’t have a big profit margin,” he says. “I would have closed already if I didn’t have these extra lines, without a shadow of a doubt.”

Even so, the shop is up for sale.

“Footfall has fallen by 50% since we started,” Mike says. “Some of it is to do with our regular customers having passed away or moved on, and we haven’t been able to replace them.” He offers another observation: “People used to come here to get seasonal stuff, but nowadays with online shopping people do it when they want to, and round here people grow it and give it away.”

He says he tried selling fish but found it impossible to supply it at the prices customers wanted to pay. “You would have to buy loads, and we simply don’t have enough customers. The profit margins aren’t there.”

Nevertheless, it is perhaps a sign of Ilminster’s resilience that it is likely the premises will be snapped up soon.

“If a shop becomes vacant it is taken up straight away,” says South Somerset district councillor Carol Goodall.

Most councillors believe Tesco has helped increase footfall to the town’s other shops. But county councillor Linda Vijeh, who objected to the opening of the superstore, disagrees and says footfall probably has risen because of the new houses built in recent years.

Tesco has its own analysis. “The car park provided by the store supports shoppers in visiting the town centre, and our presence adds to the retail offer provided by the town,” a spokesperson tells me. “Our store colleagues are really active in the local community,” he adds, “and last year they raised almost £20,000 to benefit charity.”

“People are now looking for things with a bit more personality,” says artist Carly Brown, who sells her creations in The Green House. “You can go to Nando’s and Topshop anywhere, whereas in Ilminster you’ll find something more niche.”

Indeed, the first half of 2017 saw a sharp growth in independent high street stores, according to the Local Data Company and the British Independent Retailers Association. Significantly more independent shops opened than in 2016, while the national chains saw a fall.

“Chain stores are boring and beige – these stores, the one thing they are not is beige,” Brown concludes.

So if Ilminster shops have successfully coexisted with Tesco, can they survive the threat from online? If Jinks’s predictions are anything to go by, they just might. If the traditional high streets are to survive, he believes they will have to go back to the Victorian model and contain mainly independent stores, placing a premium on service and expertise, with shopping becoming more of a social experience again. Perhaps towns like Ilminster are showing the way.

The changing face of the high street

In the first six months of 2016, 2,656 shops and other retailers closed on Britain’s high streets, a rate of 15 stores a day, according to research compiled for PwC. Those in the greatest decline include pubs, women’s clothing, newsagents and electrical goods, according to the British Independent Retailers Association, while barbers, cafés, tobacconists/e-cigarette shops, and hair and beauty salons are increasing in number.

But small can still be successful…

Independent retailers and shopkeepers account for 65% of all retail and leisure units in Britain.

Britain’s Transition Network is inspiring people to build self-sufficient towns selling local produce, thus avoiding the wastage of food miles. In 2007, Totnes, Devon, one of the first Transition Towns, introduced the Totnes Pound, which can be spent in local businesses, ensuring that money stays within the local economy, and similar schemes have been introduced elsewhere.

A pressure group successfully fought against plans for a new supermarket in Hay-on-Wye, Powys, on the Wales–England border, fearing it would cause the closure of many of the town’s independent shops, including 20 book shops. The supermarket had promised to build a new school, but the group, Plan B, came up with an alternative way the school could be built without having the supermarket.

In the Somerset town of Frome, a smartphone app called Pixie has been launched to allow shoppers to earn loyalty points when they pay for goods and services in independent shops.