The reader opens this book to be invited into “a quiet, undramatic sense of … the mystery of things”: a short walk at dusk in a garden. David E. Cooper describes the reflection of light on water, the sounds of birds and flutes, the growing darkness. He offers us the proposition, elaborated through the rest of the book, that we should regard the way of things, reality as such, as essentially mysterious; that inviting in and cultivating a sense of mystery is vital for the flourishing of human life. Yet this is “nothing special”, not a great mystical revelation, rather part of everyday life in our contact with the world “in itself”, through music, walking, and, maybe, especially gardening.

This is a philosophy book; a book, even, of metaphysics. It asks us to consider the nature of the real, how we come to know it, and how a sense of mystery lies at the heart of adequate answers to such considerations. However, these are not presented as abstract questions, but rather as central to living a good, rich and ethical life. This is an elegant and clear little volume that while rooted in Western philosophy and literature draws strongly on Daoist and Buddhist thought.

Cooper’s thesis is that the “way of things”– reality as such – is ineffable, inaccessible to literal description. Just as the Dao is nameless and for Buddhists reality is “signless”, the world “as such” is not something we can hope to understand and articulate. No descriptions are independent of human purposes and perspectives; it is, as William James puts it, impossible to “weed out the human factor”. Rather, “Things stand out for us and light up for us … only for the significance they have within a web of life, a life that is charged with desires, goals and values. A world … is a theatre of significance.”

Some may counter that science shows us the world as it really is. No, says Cooper, what science shows us is a “scientific image” of the world, one among many. It is an image that is appropriate for certain purposes, but the scientific vision strips the world of many of the qualities – colours, sounds, tastes; beauty, elegance, meaning – that make life worth living. In contrast, the postmodernists say that there is no reality outside “the text” of human construction, a perspective that Cooper dismisses as logically absurd and an impossible basis for actually living life.

The tension between these two perspectives leads Cooper to a “delicate” question: how do we accept that our world is dependent on human perspective while also seeing there is a “truly real”, not in some transcendent realm, but directly connected to the everyday world of experience? In an elegant and clear exposition, he explores the mystery of being, the “ineffable way of things”, as a “source, a well-spring, of the world of experience”. The world is a gift, and our experience of it is not an illusion but “an authentic way in which things become present to and for us”. But the gift is not otherworldly, from some creator god; rather, the way of things is itself the source or well-spring, inseparable from the world of experience. Metaphors of ‘source’ and ‘well-spring’ offer some “intimation … of the contours of mystery”.

This exploration leads us into questions of religion and religious experience. I found two of Cooper’s points especially valuable. The first is that the idea of religious faith is not a matter of believing in God or in doctrines: it is one of confidence in the way of life one is living. As Tolstoy put it, faith is “the force whereby we live”. So a life led in mindfulness of the mystery of things can be seen as a religious one. The second point is one that Cooper emphasises throughout his book: the experience of mystery, while it needs to be cultivated, is at the same time essentially “nothing special”, as Zen masters put it. Cooper is dubious about dramatic mystical experiences and trance-like visions, which he considers too separate from the everyday to lend a continuing “tone” to a person’s life.

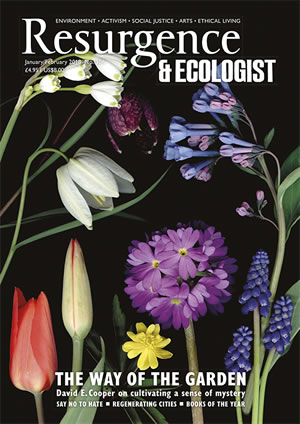

The four chapters that follow explore the mystery of our encounter with animals, with music, through walking and in gardening – this last seems to hold a special appeal for Cooper. Through these explorations he traces three faces of mystery: the mystery of the world being as it is; the mystery of its emergence through human experience; and the mystery of the nameless source of experience and worldhood. These chapters continue the clarity of exposition of the earlier chapters, drawing on a wide range of writers and sages, with a lovely selection of pithy quotes. Writing about animals, he quotes Rainer Maria Rilke: “Animals look out in the Open”; they do not “place the world against itself”. On walking, he borrows from Michel de Montaigne: “My wit does not budge, if my legs are not moving,” and with Alexander Pope he tells us that what grows in a garden is “a grace beyond the reach of art”. While these quotes certainly enliven the text, just occasionally I felt the burden of philosophical exposition: too much was being explained to me, and not enough shown; I yearned for more expressive writing that would draw me more directly to the qualities of mystery.

Cooper draws his reflections together in a chapter on Life and Mystery, which explores ethics, humility and compassion. Through ordinary practices, a sense of mystery can be cultivated. To live well, a person must be responsive to “the way of things”, appreciate the mystery with which different worlds arise from the source, rather than work out a system of rules and principles. And this takes us back to the garden, not just as a place where we cut the grass or sunbathe, but as a place where we experience the gift of being, a place where the world comes into presence.