The initial impetus for the project came from watching the geese, the pink-footed geese, on Fala Flow. When I began, I was just following a thread of inquiry - the goose skein. I think everyone cares about the geese - they really represent that turn of season - but until I went delving for information I didn’t know where they came from, why they flew like that, or where exactly it was that they landed near me. So that was where it all began.

This is the first time I’ve ever made a theatre show and the creative relationship I’ve most relished from the experience is with sound-designer and co-composer Pippa Murphy, who lives nearby. One of the chief things is that Fala Moor is five minutes from both of our houses, and both of us, independently, had a connection with the place.

One of the other lovely pieces of serendipity was that Pippa’s partner had done a dissertation through the Royal Botanic Gardens on Fala Moor. So, when I went looking for information about mosses and heather, he said: “Here you go – have this!”

I found out that on the edge of the moor had been the medieval Soutra hospital. I then started talking to one of the lead archeologists on that project and began to realize the connection between the hospital and the moor, how the mosses would have been used as wound dressings, and how many of the plants that grow in the area would have been used for medicinal purposes. So I started to think about the fact that the moor is literally an ecological sanctuary and that the edge of the moor was a sanctuary for people. It was a bit like making a jigsaw puzzle – and I began to see how all these things fitted together.

I think the land is quite contested. The moor is bordered by farmland, there’s sheep farming on the fell side and grain farming in the lower plains. In the play I perform a whole section about the skylarks because they are one of the most obvious species that you notice when you walk on the moor. Winter crops have a huge impact on skylarks by making it more difficult for the birds to nest. Most people around here know what a skylark is but most of us don’t know they are endangered. I found that genuinely shocking. That’s not to say I don’t have great sympathy for farmers, because the demand on farmers are the demands that we make as a wider society, so it’s our collective responsibility to deal with all of that.

Another prominent issue is a huge wind farm on the brow of Soutra Hill, just a mile away from the moor. Over the past few years there have been repeated attempts to build another turbine development on the edge of the moor. That’s a really difficult one for someone like me. I am a great supporter of renewable energy but it’s in total conflict with the fact the moor itself is a massive carbon source as a peat bog and also there are protected species on that land.

In Wind Resistance there is a meditation on the wind-power developments, but that doesn’t translate well into an audio experience. The sentiment is reflected in the song ‘Tyrannic man’s dominion’ [a line from Robert Burns’ song ‘Now Westlin’ Winds’]. It’s about domination of land and calling into question our entitlement to all of that. That’s one of the threads that come into the piece - whose land is this and what is it for?

One of the things I love about the theatre show is going out afterwards to meet the audience and hear what they get from it. There are people who love birds, peat bog and moss specialists, RSPB [Royal Society for the Protection of Birds] officers, and all manner of scientists and academics. Then there are also people more like me who are not experts in anything at all but it reminds them of places that they love.

I think what people really get from it is the parallel between how we treat land and how we treat people. That’s why there’s an explicit connection between looking after land and looking after life, especially healthcare and medicine, and the urgency and vulnerability of that.

Birth is an important part of the project. There is pain and life all bound up in the moment of everybody’s birth, so I really wanted to dig into that. I think most people can connect with that on one level, not just mothers and parents. We can all connect with moments in our life where something has been in jeopardy or when we needed help from other people. We all understand that, which is why the one political issue of our day that most unites opinion is the issue of healthcare.

The song ‘Small Consolation’ was a personal experience about some swallows that nested on my house. Two years in a row they built really cumbersome nests that broke, and I witnessed the deaths of fledglings. [The song describes building a bird box to help them]. If you want to protect life, give it a helping hand. For me the bird box is as much to do with healthcare and medicine as it is to do with looking after swallows.

That’s why I was really keen to centre the project on the peat bog. For many people peat bogs are desolate, nothing places. But there’s something beautiful about them: the fact that they are dark and everything of value is under the surface. To me - and I’m not the first person to make this parallel - it’s a little bit like when you’re pregnant. These things are very similar. The whole idea of being a warm, wild, wet place, it says something about how we treat each other’s bodies and how we treat these marginal bits of land.

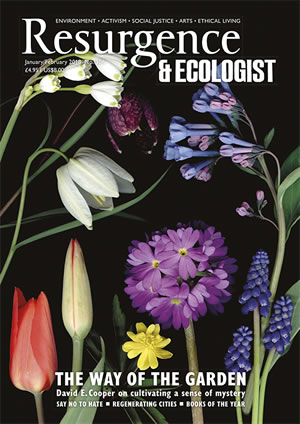

Karine Polwart was speaking to Marianne Brown, Deputy Editor of Resurgence & Ecologist. Karine’s show Wind Resistance is playing at Perth Theatre (April 17-22). A transcript of the play is published by Faber and Faber. Karine and Pippa’s album A Pocket of Wind Resistance, is out now on Hudson Records.