In October I spoke to a student union audience at Manchester University about climate change. I was particularly struck by one question about protests: “How do you justify the impacts and explain them to those who question them?” My questioner’s case study was the fuel blockade in 2000, at about the time he was born, which made me think that he was reflecting on the views of a parent, reaching that wonderful point where studies and exposure to different viewpoints from his peers led him to question what he’d taken as family gospel.

The 2000 action had been by lorry drivers protesting about rising fuel duty – a reminder that protests can be conducted from very different political directions. In the same era there was the big Countryside Alliance pro-hunting march.

But the questioning in Manchester of the very act of protest was an important reminder that many of us live in ‘bubbles’, social media or otherwise, where we take such activities for granted as a significant, and effective, form of political action. Many others do not – and it is essential that we make it clear to many more that these actions are essential, and to be celebrated.

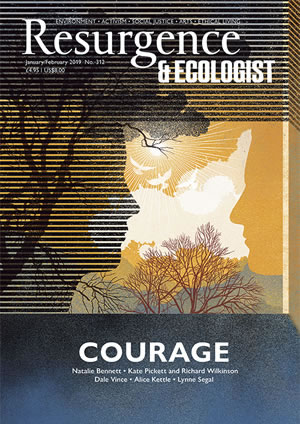

In answering the question, I referred to the suffragettes and then zoomed forward a century to the recent Sheffield protests against unnecessary street tree felling. I might have referred to the two accounts featured in this issue of Resurgence & Ecologist, from France and Germany, where long, concerted protest has had a clear and positive outcome. And to the Greenham women and other anti-nuclear weapons protests of their time, of which we’ve been reminded by Donald Trump’s recent threat to the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty signed in 1987 that came directly from their actions.

As so many such case studies indicate, change in our society isn’t granted by those in charge. It has to be forced on them – to be won. The few benefiting from the status quo are hardly going to give up those benefits without a huge struggle, and they frequently can’t see from their lofty positions that change – controlled or uncontrolled – is inevitable.

The crucial role of protest in change was true for the men and women rallying, and dying, to demand parliamentary reform at Peterloo in 1819, and it remains true for those standing up for people and planet today. The traditional political methods, petitions and letters, media stunts and reasoned argument, are not going to create transformation change, at least not on their own.

That’s not to say they’re not a crucial part of any struggle, the making of the case, but where vested interests are deeply entrenched at the heart of government they have to be confronted. The government has to know that people are prepared to put their freedom, and even their safety, on the line in resistance.

And where a society is going to have to change its entire political, economic and social approach – as we are today to get away from the disastrous neoliberal politics of Reagan and Thatcher and the growth ideology that’s dominated since the end of the second world war – then the full range of change drivers will have to be deployed.

The risks brave people are prepared to take were highlighted by the recent jailing of three anti-fracking protesters, who had ‘lorry-surfed’ at the Preston New Road Cuadrilla drilling site. The three were each sentenced to more than a year in prison for “public nuisance”. That an appeal judge subsequently described these sentences as manifestly excessive and freed them on conditional discharges a few weeks later came as little surprise, but they, and others who’ve taken similar actions, knew what they were risking. Those dicing with and defying swingeing injunctions brought by fracking companies against peaceful protests at sites across the North and the Midlands, who are putting potentially their homes and financial security on the line, are similarly aware. Yet those injunctions are a sign of the power of the protests, and how much these companies and other vested interests fear them.

These are not actions taken lightly, and such movements only emerge and develop where it is clear traditional political tactics are not going to succeed. And it often takes time for their broader impacts to become evident. The massive 2003 demonstrations against the Iraq War are often cited as a failure. But a decade later, the Labour Party voted in parliament against bombing Syria, an action clearly related back to the protest, and the whole public view of a policy of foreign interventionism continues to be coloured by that action.

The Iraq War march has been an object lesson that’s informed political action and helped develop movements in the 15 years since. A key lesson is that one action – even if it involves well over a million people – almost never on its own brings change. Protest is a process, not an act. And one of the things that happens is that protest movements learn from each other, grow out of each other, develop strengths from others’ successes and failures. The Climate Camp was informed by the anti-war protests. UK Uncut and Occupy grew out of its tactics.

Some people bring their experience from one movement to another, but one of the things that are striking in the anti-fracking protests, as in zad and Hambi, is that many of those involved have never previously been involved in politics. Protest, bravery, determination, such as anti-fracking protesters camped in the cold and the rain, waving daily to passing locals, draw in people and communities.

And they are continually evolving, learning entities, which have good days and bad, successes and defeats. I was there the week Sheffield tree protesters learnt that. There was near despair when South Yorkshire police arrested two women on private property, under repressive anti-trade-union laws. It seemed to be the loss of a crucial tactic. Yet a couple of days later, the protectors had an answer. Someone was employed to paint a householder’s gate under a threatened tree. Police were left scratching their heads – if the law was being deployed to protect workers’ ability to proceed, which workers had priority?

It’s not just a question of flexible tactics. Each movement has to develop its own methods of decision-making, of support and interaction. People bring many different perspectives and experiences to moments of high stress and pressure, and there are no rules to ensure that works effectively.

But while focusing on the successes and the achievements of protest movements, we also need to think about when protest tactics may not be appropriate and may even be counterproductive. Mistakes will be made, but they need to be learnt from. One of the things that’s marked Sheffield trees, anti-fracking, zad and Hambi is that direct actions have always been carefully targeted towards the movement goal. Sitting under a threatened tree, blocking a lorry with fracking equipment, occupying a vulnerable space, has a clear link to the cause, an immediate impact that can be explained on the evening news. The further you get from that – the more an action can simply be labelled as attention-seeking, as a headline without substance, the less likely it is to be effective.

Further, the environment in which protest operates is also constantly changing. Protests need to adapt to that, as zad has had to adapt to the removal of its initial raison d’être by victory.

One of the things we need to think about very carefully now is the febrile political age in which we live. That makes it more important than ever that protests offer hope and promote alternatives, and do not just oppose what is happening now.

The far right is promoting a politics of fear and division – and there’s no doubt it is dangerous and won’t be defeated by our adopting the same approach. We have to offer hope and inspiration, positive models and stories of how we’re not just opposing, but proposing, not simply preventing, but building, not just saying no to climate-disastrous fossil fuels, but saying yes to a just transition to a new world.

Zad, Hambi and the anti-frackers have all done that. At Preston New Road there was a wonderful case study of this – an image woven into a security fence of what the fracking field could look like without the drilling rig – trees, green fields and a rainbow of hope, fitting with a sign frequently spotted there, “FARMING NOT FRACKING”. Such creativity, beauty, play, joy are crucial to a successful protest movement – and sometimes forgotten in the telegenic moments of arrests, lock-ons and marches.

And that vision of a liveable planet, with people living in security and justice, is one that is only available to our ‘side’. Defenders of the status quo can only oppose change, not celebrate the unstable, dangerous mess their system has created. To deliver radical change, we need – and I’m confident we’ll see – far more actions like zad and Hambi.

Everyone has a role, from promoting actions on social media and answering questions from family and colleagues such as those I was asked in Manchester, to baking quiches and cakes for the protesters, to leaping on top of lorries or marching en masse. There’s a role for everyone in making a new sustainable world – a role for everyone in protesting the destruction of our wonderful planet and the exploitation of the people on it, and building a beautiful alternative. Protest is crucial to get where we need to go.