In 2018, at an exhibition of Dutch masters at the Holburne Museum, Bath, I was particularly taken by a painting of Dordrecht harbour by Aelbert Cuyp. My attention was first drawn to the rhythms of the composition as whole, to the interplay of cloudy sky and calm sea. My eye was taken more deeply into the picture by the artist’s use of light and shade. This led me to the closely observed detail – a flight of birds, a flag fluttering in the breeze, two men punting a lighter towards a ship – and back to better appreciate the whole. All this accomplished, quite unobtrusively, by a master’s skill with oil paint.

I had a very similar experience reading How to See Nature. There is profound yet unobtrusive elegance in Paul Evans’ writing. His words and metaphors subtly alter our gaze, weaving observation, science, myth, poetry into stories of beauty and tragic loss. As I finished each chapter, I wanted to close the book and let the images play through my mind, rather than rush on to the next. The book is not a blow-by-blow instruction manual as the title might suggest. It is more of an exemplar, drawing us to see things through Evans’ eyes. This is a man who knows how to look at Nature, and we could all do well to follow his example.

Since I dislike the street lights that blare down on our neighbourhood, and often worry about the impact of light pollution, I was particularly interested in Chapter Two, Gardens of Light. The first paragraphs draw us into the strange beauty of pipistrelle bats hunting insects under a sodium street lamp. The insects confuse the light with the far more distant moon, are drawn closer, and the pipistrelles follow them. Evans describes the sophisticated echolocation by which the bats hunt down the insects, and the evolution of the insects’ ability to evade them. He invites us to wonder what it is like to be a bat: maybe we draw a little closer to them as we learn that, slowed down, a bat’s ultrasound emission sounds like birdsong; slowed even further, like the sounds of whales and dolphins.

But the attraction of insects to the street light has a wider impact. It may advantage pipistrelles’ feeding, but it disrupts their circadian rhythms, interferes with flight paths that require darkness. Some one-third of insects die as a result of encounter with artificial light, which confuses and disorients them; it exhausts them, makes them vulnerable to predators, and diverts them from pollinating flowers. As the chapter continues, the reader sees the relation between light, insects, bats and flowering plants through the author’s eyes and sensemaking, so feels present with both the wonder and the disturbance of the phenomenon.

Each chapter picks up and explores a theme: rosebay willowherb cracking open seed pods like “fans of white feathers” leads to a reflection on plants of the wasteland; the warning call of grouse takes us onto the wild moors; the glimpse of a pine marten (or was it a polecat?) to questions of reintroduction and rewilding. That all is not well with Nature we learn in particular in the chapters on The Greenwood and Blight, where we see how human interventions often have unforeseen impacts, unbalancing ancient relationships. The book ends with a Bestiary of British wildlife, “idiosyncratic in its selection and based on personal encounter”, which brings the reader closer to Adder, Badger, Crow … Yellowhammer, Zooplankton.

Nature writers in this time of ecological devastation face two challenges: one is to draw attention to the losses caused by human action; another is to tempt us into an ever-deeper appreciation of the intricate beauty of the more-than-human world. Who can say which is the more important? In this book, Evans successfully integrates both. He writes, “I intend the perspective of this book to be one of advocacy for what we see – bringing overlooked wildlife into focus as a way of revealing how much it matters… [For] seeing Nature as a resource to be exploited and commodified is a denial of its intrinsic value.”

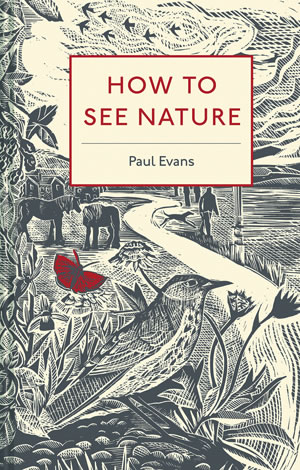

How to See Nature is handsomely produced by Batsford; readers will enjoy the illustrations by the author’s wife, Maria Nunzia. It shows that even in these times of ecological catastrophe, human culture can reflect the intricate beauty of the world around us.