What happens “when we dare / to be as bold as peregrini – / monks who cast away their oars / to let the spirit in the wind / direct them on their journey?” This is one of the threads that lead us through James Harpur’s latest volume of poetry. Harpur is preoccupied by whether the created world should be embraced or shunned in order to gain a better understanding of God. This is a concern found in all religions and beliefs. Harpur is well versed in many of them, though his erudition is never showy. On the contrary, it steers his investigations away from the purely personal towards an interrogation of what faith is and means.

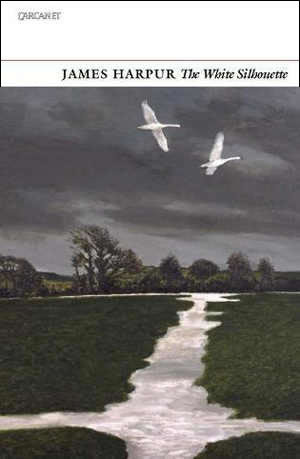

The journey begins by travelling east, a Christmas journey from Cork to his sister’s house in Dorset. This section, The White Silhouette, concerns the great distance that exists between our perception of heavenly things and our ability to touch them: Harpur gazes at the Perseids going over; at images disfigured by iconoclasm or time, “your features … too full of light for this world, assaulted by the stares of believers / and unbelievers”. The eponymous poem traces the anguish of the one who would believe but who faces an apparently insurmountable gulf between the everyday and the transfigured life; after years of searching, too hard, disillusion sets in, “And yet / I still write to you, poem after poem, / Trying to shape the perfect pattern / Of words and the mystery of their rhythm, / An earthly music audible in heaven”.

Kells is the sequence that is the fulcrum of this collection. Harpur alternates between the voice of the 21st-century poet staring into the illuminated manuscript like a haruspex, and the voices of the scribes, monks and thinkers who reply. We begin in the wash of a Celtic sky over Iona; the scribe repeatedly faces the impossible task of speaking about the ineffable. The scribe is both figurative and real in his labour, working gold literally with his pen and symbolically with the gold of the scriptures. The implication is that the poet does something similar.

Harpur uses a short, slightly offbeat line, irregularly rhymed, that both awakens lyricism and deliberately works against it. The poem turns in a double helix; themes are revisited under different lights. This enriches metaphor and prevents us arriving at over-hasty conclusions. Here are serious questions about kataphatic and apophatic ways of thinking about God, the possible need to choose between “perfection of the life or of the work”, and the temptations of accidie and despair. Though the context remains a predominantly Christian one with Buddhist undertones, these poems are a quest for wisdom that has resonance at all times and in all places: “Home can be an island or a scriptorium, / a chapel or a book, / a place or spiritual condition”. Finally the female vision he has – is she Sophia? – tells us these endeavours are indeed worthwhile, “the process is the crux … as when the tapestry we’ve only seen / from behind as dangling threads, / the messy details of our story, is now revealed, and home at last, we see our pattern in brocaded glory, / the confluence of lines of light”.

The last section, Leaves, seems at first something of an anticlimax; there is a lessening of poetic tension as versions from Homer, Virgil and Horace are interleaved with memories of Harpur’s dead family and friends. But perhaps that is the point. As he says in Kells, you can miss God by looking too hard. It is the achievement of Harpur’s delicate and serious poetry that he reminds us of this fact.