“What do we want?” a woman shouted into a megaphone as the London rain poured down upon Extinction Rebellion last October. The crowd responded in unison: "Climate justice!"

One of the many striking shifts that have taken place in the climate agenda over the past year is how the social dimension and the centrality of justice have come to the fore. No longer is climate action only about cutting carbon emissions to zero and building up defences to inevitable physical shocks. From the start, Greta Thunberg and the School Strike movement, along with Extinction Rebellion, have made the issue deeply personal, highlighting in particular how the prospects for today’s children are being stolen by continued emissions of greenhouse gases.

In fact, if left unchecked, climate breakdown will become one of the world’s worst injustices in terms of the depth and duration of the damage it will cause for centuries to come, hitting those hardest who contributed least to the problem. As Pope Francis has made clear, we need to take action “to avoid perpetrating a brutal act of injustice towards the poor and future generations”.

The climate justice agenda goes further still, looking at how the causes and consequences of global heating are often refracted through the lenses of gender, race, colonisation and class. For Mary Robinson, in many ways of the godmother of climate justice – see The Climate Justice Now Generation, Issue 315 – it means “we need to create a ‘people first’ platform for those on the margins suffering the worst effects of climate change.” Added to this is the human and political imperative to make sure that the road to a clean, green economy not only delivers positive social progress, but also does not marginalise people. In other words, we need a just transition too.

For too long, the climate agenda has been socially blind. In the US, President Trump was able to enlist the support of coalworkers in the USA fearful for their jobs. In France, President Macron’s plan to introduce a carbon tax on vehicles prompted the gilets jaunes ʻyellow vestsʼ backlash, with one protester memorably saying: “You care about the end of the world; we care about the end of the month.” As the UK’s Committee on Climate Change puts it, “if the impact of the move to net-zero on employment and the cost of living is not addressed and managed, and if those most affected are not engaged in the debate, there is a significant risk that there will be resistance to change, which could lead the transition to stall.”

Over the past two years I’ve been working intensively on the just transition both in the UK and at an international level. It’s clear that the transition is a good news story, one that could well lead to many more jobs, and vastly improved health and remove a large source of corruption and conflict in the world by phasing out fossil fuels – as well as avoiding climate catastrophe. But I’ve also learnt that these benefits are not automatic and new approaches are needed to consciously steer the process of change. This is also the agenda of the Green New Deal, a strategy designed to confront decarbonisation and inequality simultaneously, that is gathering increasing support in both Europe and North America.

At the heart of the just transition lie questions of participation and power. Starting in the labour movement in the 1970s, the just transition has focused on how the interests of workers and communities can be respected as dirty industries are phased out and the clean economy is scaled up. For Paul Nowak, Deputy Secretary General at the Trades Union Congress, this means that workers need to be at the table: “Nothing about us, without us,” he says. Workers have to be involved in climate decisions that will influence their future, they need to have the skills to enable them to thrive and they need to be confident that green jobs are also good jobs. Sadly, at UK offshore wind farms, the rate of accidents is about four times higher than in offshore oil and gas, with lower rates of unionisation one explanation.

A just transition will also need to be guided by the priorities of place. Geography has determined the location for the world’s carbon-intensive sectors such as coal, oil and gas as well as iron and steel. New green sectors are rarely in the same location. In the UK, carbon emissions peaked in the early 1970s as deindustrialisation got under way, in the process offshoring much of the pollution to developing countries. Decades later, the result has been the creation of the most regionally imbalanced economy in Europe. Not surprisingly, there’s understandable concern in many parts of the country that the drive to zero carbon could simply exacerbate this trend. Avoiding these carbon divisions requires stronger powers at local and regional levels to deliver climate plans that meet their needs, backed up by a more decentralised financial system. Positive signals are coming from the bottom up in terms of community energy projects, along with new city-level climate commissions. In Yorkshire, the TUC has set up its own Low Carbon Task Force to drive the process forward.

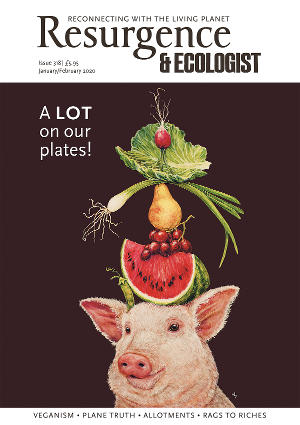

To date, the focus of the just transition has been on urgent changes needed in the energy shift. But a similar transformation is needed in terms of food and land use, not just to respond to the climate crisis but also to end the loss of biodiversity and revive rural communities. For Mike Berners-Lee, author of There is No Planet B, “a sustainable food and land system offers a huge net livelihood opportunity”, one that can lead to more jobs with better working conditions.

Making these connections between climate, Nature and justice has to become a national endeavour. Scotland has taken the lead, setting up a multi-stakeholder Just Transition Commission to show how a climate-neutral economy can be “fair for all”. A similar initiative is needed at the UK level too, in order to ‘people-proof’ the strategy to build a zero-carbon economy. A top priority needs to be the Treasury’s policies for tax and spend. Carbon prices, for example, need to be designed in ways that leave low-income households and vulnerable communities better off, and matched by a National Investment Bank to mobilise the capital required.

More than this, the just transition could become an essential part of delivering an ambitious outcome at the COP26 climate talks in Glasgow this November. As countries come forward with their new climate targets, these should be accompanied by just transition plans. Some countries are already stepping up, not least South Africa, which is designing an ambitious just transition transaction to pay for phasing down its ailing coal-based power sector and boosting renewables in ways that respect workers and communities, all set against a backdrop of entrenched poverty and high unemployment. Bold approaches to increasing public finance and channelling private capital are going to be essential to make this happen. The stakes are high, according to Fiona Reynolds, chief executive of Principles for Responsible Investment, the US$80 trillion-plus alliance of investors working on environmental and social issues, who argue: “Unless we get the just transition right, we won’t win the climate battle.”