Chris Packham is at the beginning of an epic drive from the New Forest in southern England to Inverness in the Scottish Highlands, where he is set to record BBC’s Autumnwatch. He has stacks of books in the car – that’s why, he says, he can’t take the train – and on the passenger seat next to him sits a pile of vegan snack bars. Despite the gruelling 10-hour journey ahead of him, his outlook is sanguine. “I’ve downloaded a couple of audio books,” he says.

Changing his travel habits – he’s offsetting long-haul flights out of his own pocket and says he intends to threaten not to fly if his colleagues don’t do the same – is not the only lifestyle adjustment Packham has made over the last year. To much social media fanfare, he joined over a quarter of a million people in going vegan for Veganuary in 2019, and has stuck to it since then. Apparently it hasn’t been difficult. “Have I had cravings? Not one. I’m not that sort of person,” he told Resurgence & Ecologist shortly after setting out. “I went to Mexico for three weeks in March for work. I didn’t have any trouble finding vegan food. I had rice, avocado, salad. But that’s all I had for three weeks. By the end I was fed up eating exactly the same thing. That was the only time psychologically I thought, ‘Damn.’ ”

Finding vegan snacks, ingredients, and options at restaurants was easy, he says. According to Veganuary’s stats, other participants had similar experiences. Sixty per cent said the challenge was easier than they had anticipated, and 51% felt their decision to stay vegan was influenced by “the discovery of great-tasting food”.

Restaurant chains and supermarkets are riding the wave, and sales of Greggs’ vegan sausage rolls and Pizza Hut’s vegan pizzas reportedly soared during the campaign. But is going vegan a bit too easy? Could the lack of emotional investment lead to this becoming a passing phase? “We live in an instantaneous age,” Packham replies. “If it wasn’t easy people probably wouldn’t go for it.”

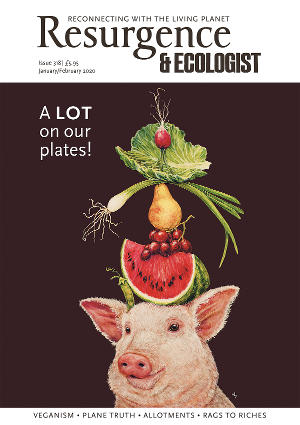

In addition to animal welfare, Packham has listed the environmental crisis as one of the main reasons – see An Alternative Worldview, page 32 – he decided to go vegan. As consumption lies at the core of the economic system feeding this crisis, is there a problem with businesses cashing in on the trend, and consumption – becoming vegan – being seen as a way out? “At this point in time we should be encouraging those companies that are taking on the vegan thing,” Packham says. “We have a bigger thing to deal with and that’s too much meat being eaten.”

That said, going vegan isn’t an instant fix, he adds. A lot of processed vegan food contains palm oil, which continues to be a major driver of deforestation in some of the world’s most biodiverse areas. “Also, the idea that you could click your fingers and everyone would go vegan overnight would be disastrous for the planet,” he says. “At the moment in the UK our low-impact, organic mixed farms with livestock with good welfare standards and so on are really important for maintaining biodiversity.” Some farms he has seen have more biodiversity than national parks, he says, because they are managed for wildlife. “If you say we just want a veg-only diet, most of the vegetables grown in the UK are grown under intensive agriculture, which is no good for wildlife at all. What we need is a gradual change.” Packham advocates buying straight from farmers and avoiding supermarkets wherever possible. “I’ve got an issue with supermarkets: they are culpable when it comes to environmental damage, especially in the UK,” he says. “The point is they cripple British farming with their price-fixing. They import food we could produce in this country with a far smaller carbon footprint.”

This suggestion, he admits, is sometimes met with scepticism. “Some people say to me, and I hear this a lot, ‘It’s OK for you – you can afford it,’ because food in those outlets is a lot more expensive than it is in the supermarkets.” They have a point, don’t they? I ask. “We’re all different. Sometimes it’s a mental attitude thing, sometimes it’s a cultural thing, sometimes it’s an economic thing,” Packham says. “There are way too many people in this country dependent on food banks. It’s a social crime of enormous magnitude.” And things are getting worse. According to the Trussell Trust, which runs 1,200 food banks across the country, there was a 23% increase in food bank use between April and September 2019 compared with the same period in 2018. Clearly, not everyone has a choice. “But if you are someone who has a choice, then exercise it,” Packham says.

When I first interviewed Packham in early 2019, he had just returned from a visit to the vet with his elderly miniature poodle, Scratchy. Scratchy died in October, leaving Packham devastated. He and his partner, Charlotte Corney, who runs the Isle of Wight Zoo, decided to bring home two of Scratchy’s relatives, whom they have rather inexplicably named Sid and Nancy. Packham has commented that he would never feed his dogs vegan food, but pet food has a substantial carbon pawprint. (See Wake Up, Conservation Movement!, Issue 314.) Can you be an ethical dog owner if you are feeding your dog meat? “I tweeted this a while ago about pet food and the environmental impact of canned pet food: it’s disastrous, absolutely disastrous,” he says. “I’m not pointing my finger at dog or cat owners, because they just genuinely don’t know it. They just think it’s a by-product, but it’s disastrous.” So what does he feed his dogs? “I’m feeding them raw food. The food is organic and there are a number of suppliers you can get organic by-products from. I’m mixing it with meat I’m sourcing locally, so they are having venison and other bits of deer which are culled locally, and I mix them together.”

Change is necessary, but people set out at a different pace, he says. So far, Packham has ordered an electric car (and is annoyed to still be waiting for it) and has switched to a green energy supplier as well as addressing flights and food. “I’m not saying I’ve got it right, by the way – I’m here with my [snack] bars and they’re all wrapped in plastic. You could say to me, why haven’t you got four apples lying there that you grew in your garden? Well, personally I don’t eat fruit. I’m a vegan who doesn’t eat fruit. Do you know what I mean? We’ve got to give and take. We should be encouraging of one another.” Shortly afterwards, we say goodbye and I leave him to continue his journey.