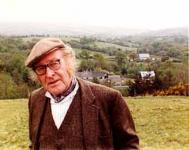

JOHN SEYMOUR FIRST burst into my life in 1973, when the thunderclouds of the oil crisis and the miners' strike were hanging heavily over Britain. As regular blackouts darkened living rooms, and as petrol queues stretched across the urban landscape, John merrily raised his voice to sing the praises of the good life, away from it all. Give up fossil fuels! Everybody back to the land!

John could be described as a one-man rebellion against modernism. Harbouring profound doubts about the world of cities, cars and consumerism, he wanted to know what kind of existence people are best suited to. After studying the great diversity of human lifestyles for many decades, his uncompromising answer was: people should try to live close to nature, and they should seek to be self-reliant in food as well as entertainment. John was a profound thinker, but he was much happier working in his garden and dancing a jig on a table in an Irish pub than giving a worthy speech in a crowded lecture theatre.

John was best known as the author of The Complete Book Of Self-Sufficiency, which sold millions of copies in twenty languages. First published in 1976, it helped to launch a new social movement - encouraging disillusioned city dwellers to pack their bags and seek a more wholesome rural existence. For the last thirty years it has had an enduring appeal to all those who wanted to learn about growing their own vegetables, making cheese and jam, and curing bacon. It was republished just before John died, with the subtitle The Classic Guide for Realists and Dreamers.

But John insisted that living off the land should not just be a self-interested pursuit. He summarised his philosophy in the introduction of another book, The Lore of the Land: "According to the book of Genesis, God put the Man and the Woman in the Garden to 'dress it and keep it'. Whether we look upon Genesis as divinely inspired or not, it is obvious that we should do just this. We should hand the land on to the next trustee better, more fruitful, more beautiful, and richer in living creatures than it was when we took it over."

In all, John wrote forty-one books, and many articles in Resurgence, covering travel, rural crafts, gardening and environmental philosophy, but his abiding mission was to preach the gospel of self-sufficiency. It was a theme that first came to him as a young man, when his family moved from Hampstead, north London, where he was born, to Frinton-on-Sea in Essex. There, he experienced a wondrous and colourful world of people farming with shire horses, tending their cottage gardens and catching herrings and salmon in small boats. This vision of a life close to nature would stay with him for the rest of his days.

John's mother was an American of Welsh extraction - perhaps why one of his earliest dreams was to become a cowboy. A career in his stepfather's chewing-gum business held no interest for John. Instead, he decided to study agriculture at Wye College, Kent, after which, at the age of twenty, he went to South Africa under the auspices of the Settlers' Memorial Association.

He soon found a job on a farm with 200,000 sheep. When he got the manager's position on a farm farther north, he chose to spend much time with bushmen, whose assured hunter-gatherer lifestyle in a semi-desert environment deeply impressed him and profoundly influenced his thinking. John came to realise that much of human culture is an ancient inheritance, and not primarily the product of urban progress.

One of John's friends was a bushman called Joseph: "What I learned from Joseph was to have great respect for nature. They treated the other animals of the soil community as equals… Killing for killing's sake was inconceivable to him. Joseph respected the animal he killed out of necessity. His relatives danced at night, by firelight, closely imitating the animals they hunted by day. Joseph's ancestors depicted these same animals, often being hunted, on the walls of caves all over Africa. Modern bushmen no longer do this because they have been driven into country where there are no caves - no rocks."

During the Second World War, John saw service in Ethopia against the Italians, and in Burma he took part in ferocious fighting against the Japanese. But at the end of the war he was moved to outrage when he heard the news of the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima: "I was disgusted about it. Bombing civilians, women and little children. I cannot forgive the Allies for it. I thought it was a sordid, low-down thing to do and I've never got over it". After returning to England in 1945, he decided to travel overland from Europe to India for the BBC. On this epic journey he experienced a vast variety of ancient cultures still dominated by peasant farming and herding. Back in the UK, he was still in explorer mode, working for a time on one of the last sailing barges on the east and south coasts captained by Bob Roberts. From him he learned many sailors' songs, and, later in life, loved reciting them around campfires and at rowdy parties.

In the late 1950s, John and his wife Sally and their three daughters moved to five acres of land near Woodbridge, in Suffolk. In BBC radio programmes, and in such books as The Fat of the Land, he explored the concept of self-sufficiency, which he saw as an antidote to the emerging dependence culture that robbed people of dignity and self-respect. He wanted people to declare their independence from industrial society, emphasising that there was more, much more, to life than a nine-to-five desk job.

None the less, although John was not fond of urban life, some of his best friends, among them the poet William Empson, were city-dwellers, and he was thus at the heart of many a London party, and loved a lavish Chinese meal in Gerrard Street. In London's West End he certainly stood out in his tweed jacket with its red Indian handkerchief, corduroy trousers and brown leather brogues.

In the 1970s John and his family moved to a farm in Pembrokeshire, west Wales. When The Complete Book of Self-Sufficiency started rolling off the press in huge numbers, readers began streaming to his farm, which he called The Centre for Living. All were given a meal and a bed, sometimes in the hay barn. The royalties from the book were spent as quickly as they accrued - on hospitality, on rebuilding the barn after it was burned down by careless guests, and on repairing farm equipment damaged by clumsy visitors. Yet in the middle of this turmoil John kept on writing, producing on average two books a year. He started speaking at conferences with other visionary thinkers such as Leopold Kohr and E. F. Schumacher who pioneered the 'Small is Beautiful' concept to which he subscribed with great fervour.

In the mid-1980s, John and I spent three years making the BBC series and co-authoring the book Far From Paradise, on the history of human impact on the environment. This project took us to many parts of the world - the remnants of the ancient city of Ur and the salty wastes of Mesopotamia, the last remaining villages in Europe where people still farmed without tractors, the acid-rain-damaged forests of Germany, the eroding farmlands of Kansas and the skyscrapers of Manhattan. The first-hand evidence we collected of the ever-increasing impact of an industrialising, urbanising humanity on its host planet was a shocking experience for us both.

To cheer ourselves up, we co-authored Blueprint for a Green Planet in 1987, one of the first books emphasising personal responsibility for countering environmental destruction through green consumerism. We argued that people would start making different choices once they were better informed about the environmental impact of a badly insulated house, a packet of washing powder, or a humble hamburger. Sadly, the publishers refused to include our final chapter, which linked personal decisions and the need for collective action.

In the last eighteen years John continued to write books celebrating all aspects of rural life. For most of his last two decades, he lived in County Wexford, Ireland, and ran the School for Self-Sufficiency. Participants came from all over the world wanting to meet 'Mr Self-Sufficiency'. Evenings were for storytelling, playing the harmonica and singing sailors' songs - John had the extraordinary memory of a man who refused to clutter his mind with television programmes, even if he loved presenting them.

In Ireland John made many friends. He sang the praises of the Emerald Isle and was distressed about the impact of the European Union on its rural culture. He never shied away from speaking out and taking action against the things he believed were wrong. In 1999 he joined with a group of activists who destroyed genetically "mutilated" sugar beet planted by Monsanto. The resulting court case achieved wide publicity and did much to alert public opinion to the dangers of uncontrolled technology and "irresponsible multi-national corporations".

In the last eighteen months of his life, John was back on his beloved Pembrokeshire farm with his daughter Ann, telling stories to his grandchildren and writing rhyming poetry, with an acerbic wit that was his last weapon against what he saw as our destructive era. John's primary concern was that we should not readily give up a world that had been so long in the making - a world of hunter-gatherers, small-scale farmers, herders, sailors and foresters. Should we not think twice before we launch headlong into a plastic, fossil-fuel-powered, environmentally destructive age?

John was as much at home in the humblest house on a hillside as in the manor house of landed gentry. He was like a force of nature, always willing to listen, always interested in learning about new - or very old - ways of working the land. John wrote: "I am only one. I can only do what one can do. But what one can do, I will do!"