The scope of climate action is almost inconceivable, from the smallest daily decisions we each might make to the widest global coalitions of governments, civil society groups and social movements. To change everything, as the saying goes, we need everyone.

Change might broadly be achieved through two sets of overlapping tactics: appealing to existing powers, and reclaiming power. Over recent years, we’ve seen the latter surface through social movements that have mobilised strikes and mass demonstrations, as well as the former through global climate negotiations and declarations made by centralised governments, institutions and corporations.

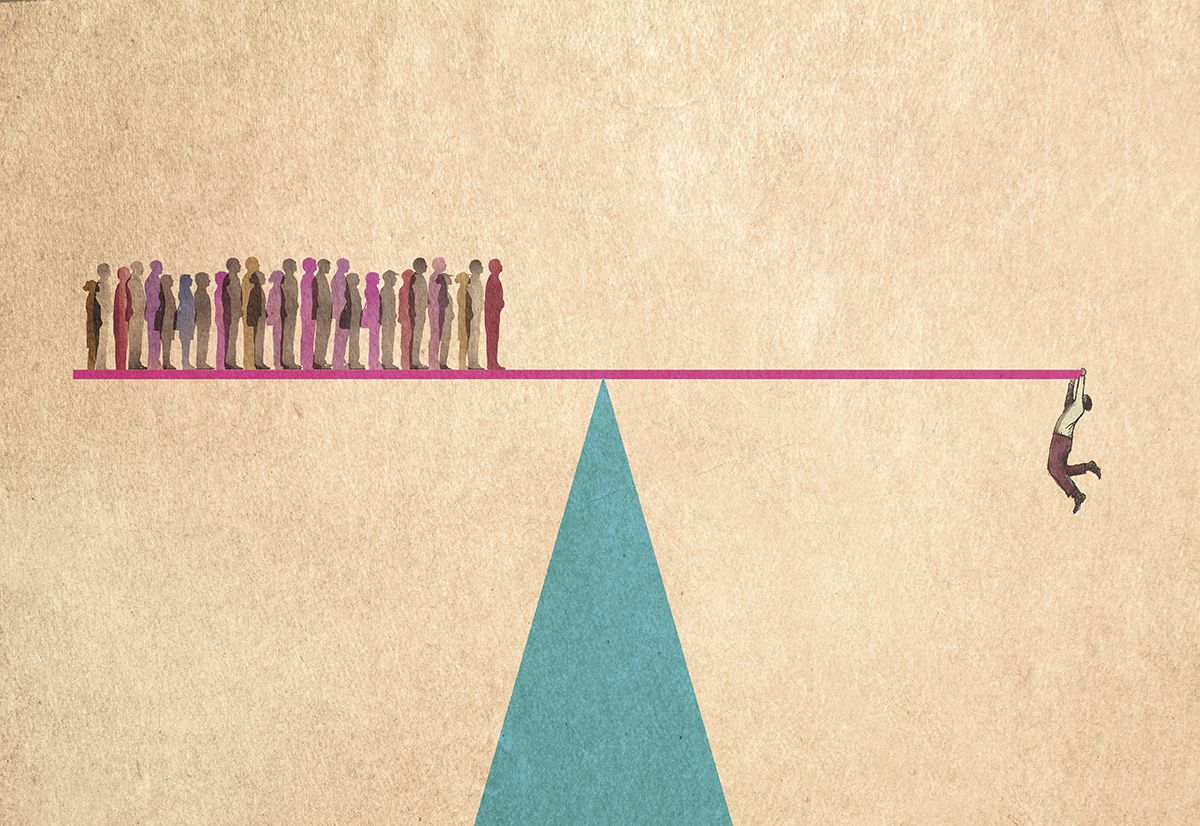

Everything that happens across this spectrum is united by two key questions: who holds power, and what should they do with it?

In answering this first question, a cross-party group of 32 UK mayors is demanding a ‘power shift’ to local and regional authorities. In a joint statement, they called for “new powers and resources to be devolved from Whitehall to shape local energy markets, decarbonise transport and tackle emissions from homes and offices”.

Lord Deben, chair of the UK’s independent Climate Change Committee, urged Boris Johnson, the prime minister, to heed the mayors’ call, arguing that delivering effective climate action depended on the close linking of local and central government. This ‘shift’ would be enshrined in a proposed Net Zero Local Powers Bill, and supported by a toolkit to guide local authorities on how to get involved in the COP26 climate talks.

This rhetoric of devolution – a tussle between local and central powers – will be familiar after years of wrangling over Brexit. But, having ‘shifted’ power from one space to another, that second question – what should we do with it? – is as (if not more) important. Shifting power around within a broken system is not enough. We need to change the terms upon which decisions are made, and not simply replicate badly structured, poorly run, profit-driven institutions in microcosm. A genuine ‘power shift’ would mean radically reimagining public services and public spaces, and meaningfully altering the relationships between individuals, local communities, and wider structures. It means thinking beyond decarbonisation and working towards climate justice.

I write from Bristol, the first city in the UK to declare a climate emergency. “As we rebuild, recover and reconceptualise cities after the pandemic, local leaders need powers and resources from government to make these opportunities a reality,” urged Bristol’s Labour mayor, Marvin Rees.

Rees’s flagship project is City LEAP, a green energy and infrastructure partnership and joint public–private enterprise. A commercial partner, yet to be decided, will invest one billion pounds in the project, and control 50% of the shares in a joint-venture company. The project was celebrated by Polly Billington, chief executive of UK100, which represents over 100 mayors and local authority leaders committed to action on climate. But, she argued in the Times, initiatives like this also “divert us from the reality facing local leaders: the absence of a coherent national strategy or framework; insufficient powers to drive big changes; and insufficient capacity to use [these powers] decisively”.

On the ground, Bristol city councillors fear that the LEAP partnership carries significant financial risk, especially in the wake of the Bristol Energy scandal, which saw multi-million-pound losses. City-wide initiatives are as much in need of scrutiny and accountability as bigger, national ventures, especially when they are working with commercial imperatives.

If ‘power shifts’, we must be sure that it’s heading in the right direction – not just vertically, from top to bottom, central to local – but horizontally, from private enterprise and out to community-owned and community-led solutions that put people before profit to craft a genuinely just transition.