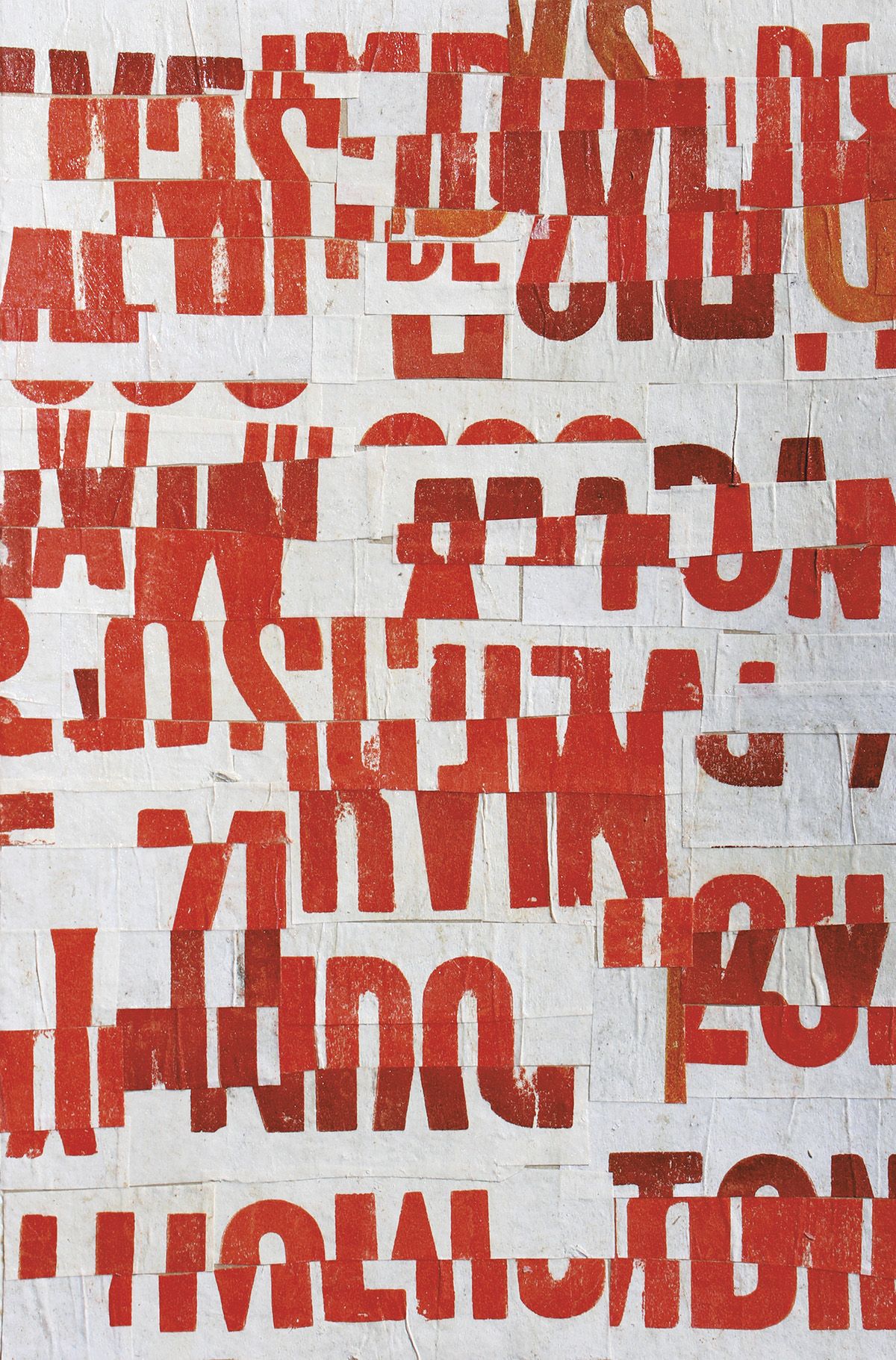

No more mixed signals, please.

The yearly UN climate summit or Conference of the Parties (COP) produces international agreements that guide countries in their response to the climate crisis. At least, it should.

Instead, the climate pacts so far have largely played into the already inaccessible climate discourse. High-minded rhetoric excludes the people most impacted by the climate crisis by keeping its language confusing and difficult to communicate. The vagueness of the language means that countries most responsible for the climate crisis can easily take advantage of the situation to benefit themselves. We saw this in the use of seemingly similar words like ‘should’ instead of ‘shall’ in the 2015 Paris Agreement, which suddenly signalled a less intense commitment from global north countries to lead the way in reducing emissions.

At COP26 in Glasgow last November there was a lot of attention on the switching of coal phase-out to coal phase-down. Developed countries most responsible for the climate crisis were “disappointed” by India’s intervention. It is true that the language was watered down. However, something just as crucial was not just switched out but erased – the concrete mechanisms for climate finance to be transferred from developed countries to developing countries for loss and damages were reduced to a dialogue. With this crucial information in mind, India’s intervention makes more sense when the global north countries most responsible for the crisis refuse to pay climate reparations.

Language is used as a tool to compromise and delay action. Why are the parties at the COP still acting as if there are compromises to be made with the worst polluters and emitters? The climate crisis presents itself in no uncertain terms: billions of people across the globe are already experiencing the worst impacts.

Weakening key phrases of landmark agreements does us no favours when we are surer than ever of what we stand to lose as we inch closer to ecological and climate collapse. There can be no room for uncertainty, no ‘shoulds’ taking the place of ‘shalls’ and ‘musts’; no calling for measly ‘phase-downs’ when what we need are complete phase-outs alongside reparations for loss and damages experienced by global south countries and for adaptation. For the global north to dodge and diminish the overwhelming urgency of widespread, systemic climate action is to sign away the lives of millions upon millions of the most vulnerable populations and groups.

Six Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports have been published, each more pressing than the last in calling for immediate and global climate action. Why is this watering down still happening? The latest IPCC reports have already explicitly named colonialism and other socio-economic injustices as active drivers of communities’ vulnerability to the climate crisis. Both the IPCC and grassroots movements have long demonstrated that dirty industries have no place in any sort of climate-resilient society. The only thing left is for world leaders, through COP, to make a definitive choice: profit, or people and planet. We must consign the dirty industries to the past, or we have no future.

The COP27 agreement cannot be just another text that serves dirty industry and energy lobbyists to hinder genuine progress and climate justice. We demand nothing less than clear-cut messaging across the board to single out the worst perpetrators. Global north developed countries need to be explicitly held accountable. We need to see real mechanisms put in place to hold the largest polluters especially to their promises and pledges of deep emissions cuts. We need concrete mechanisms to facilitate climate reparations from the global north to the global south in the form of finance and technology transfer, both to minimise and manage loss and damages and to adapt and transition into a renewable energy system.

Yes, language matters. But at the end of the day it is only a reflection of the political will of leaders and their willingness to actually bring the COP agreements into policy. The landmarks we have seen so far of language being clearer in naming the systems that are destroying the planet have been a feat of the people – civil society, scientists, the most marginalised sectors – pushing leaders to enact the people’s will.