In the face of the climate emergency and a crisis in the state of Nature, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed. But a subtle change in our thinking about the environment could help us overcome some of those feelings of powerlessness. And environmental researcher Philippa Bayley and visual artist Neville Gabie may have found a way to help us do just that, with their project living-language-land.

In 2021 they began to approach speakers of endangered languages all over the world and asked them to share words that reflected their relationship with the land. “We wanted to create a window into different environments and landscapes and the diverse ways in which people live,” explains Gabie. “And the project was a profound lesson in the joy of listening. It’s not until you open yourself up to the experience and knowledge of other voices that you can begin to make that journey of empathy. And listening has changed the way I see and understand my own experience through understanding a little of how other communities connect to the Earth, to Nature and to one another.”

Over a period of eight months they invited contributors to offer their chosen words, and they shared them, one by one, on a dedicated project website accompanied by visual art and film. Then, in the November, they presented their work in the Green Zone at COP26 in Glasgow. In 2022, which marks the beginning of the UN International Decade of Indigenous Languages, the project couldn’t be more relevant.

The UNESCO World Atlas of Languages reports that there are more than 8,000 documented languages globally, around 7,000 of which are still in use. But according to the Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages more than 3,000 are in danger of being lost before 2100. Given that the planet is also in crisis, and because language is so crucial in conveying not only the spirit of a place but also the relationships between all the living beings in it, what better way could there be than this unique project to bring all these elements together?

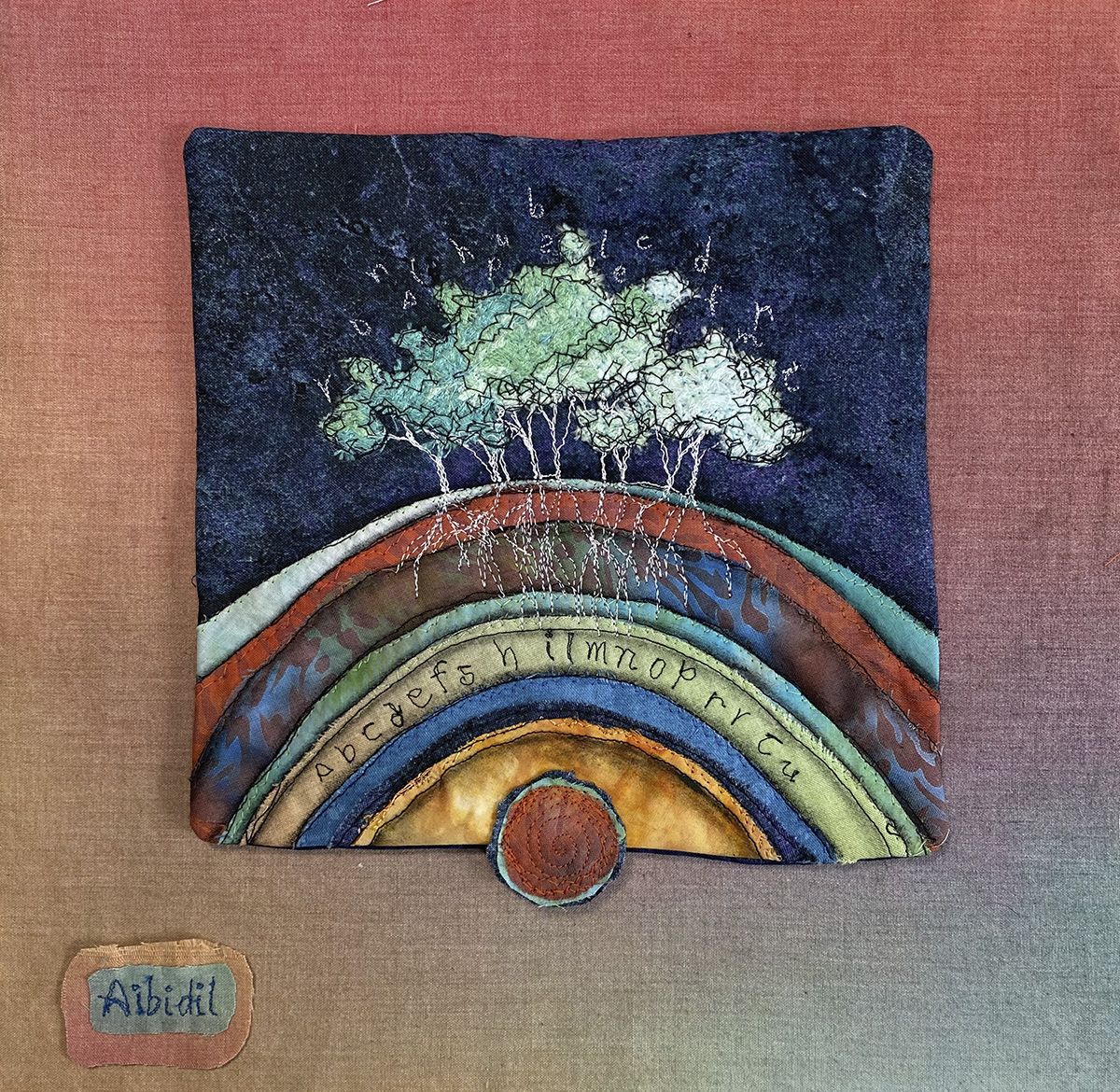

The sheer variety of concepts within the collection is surprising, and the contribution of Scottish artist Malcolm Maclean seems to encapsulate it in a particularly pertinent way. His word, aibidil, is Scottish Gaelic for ‘alphabet’. Gaelic is one of the oldest languages spoken in Europe today, and each of the 18 letters of its alphabet is represented by a tree. In the film accompanying his contribution Maclean shows us the work of retired forester Boyd Mackenzie, who has planted each of these trees on his Hebridean croft, creating a living alphabet we can all walk through.

“Gaelic was almost invisible in public life in Scotland until the 1980s and 1990s,” says Maclean, who, as an arts and heritage consultant and a tireless champion for the revival of Scottish Gaelic, was an obvious choice for the project. A former chair of UNESCO Scotland, he is delighted about the International Decade of Indigenous Languages: “You can imagine how pleased I was for them to declare it,” he says, “and I hope to get involved in other projects.”

Academics Helina Hookoomsing and Shameem Oozeerally from Mauritius share his enthusiasm. “We believe that traditional, Indigenous languages, knowledge and heritage are among the most important cultural systems for ecological, social and climate justice,” says Hookoomsing. She and Oozeerally, who both specialise in ecolinguistics, contributed the Mauritian Creole word danbwa, meaning ‘into the woods’ or ‘wilderness’. Mauritius has no human Indigenous population and therefore no Indigenous language. “The Indigenous population of the island is the flora and fauna,” says Hookoomsing, adding: “Shameem and I believe there is a deep, almost umbilical, connection between language and our environments – not only in terms of how we speak about them, but how we interact with the Earth.”

This concept of interaction with the Earth is echoed throughout the project, and Lakota contributor Tiokasin Ghosthorse from the USA has a striking way of expressing the idea. The Lakota word wíyukčaŋ, meaning ‘consciousness’ or ‘knowing’, reflects the idea of being a part of Nature, not outside of it, and Ghosthorse explains how his language is one of verbs rather than nouns: “To us the sun is a verb,” he says, “because look at what it’s doing and being, and it’s always alive. If you maintain a relationship with the Earth, rather than being in control of it, then all life will be here. Of course we need the Earth, but she also needs us. We are in a relationship, so our language reflects that relationship.”

In encouraging us to examine the language we use to think about Nature and the environment, living-language-land offers us the tools to explore that relationship and to engage with Nature in a positive and reciprocal way. Before embarking on the project, Bayley, who works in the field of public engagement and research management, was inspired by the book Braiding Sweetgrass by ecologist Robin Wall Kimmerer, in which Kimmerer writes: “To be native to a place we must learn to speak its language.”

Says Bayley: “At the time, I was experiencing a sense of fatigue with some of the traditional methods of environmental campaigning. In the face of an increasingly urgent situation, the temptation is to shout louder. But another way of approaching it is to explore different languages or ways of communicating. And this book made me think, how can we expand the lexicon of our relationship with the natural world in a way that is both gentle and powerful?”

Along with their contributors, both Bayley and Gabie welcome the International Decade of Indigenous Languages as an opportunity for change. “We want to challenge the lingua franca of the environmental crisis,” says Bayley, “and to build on the foundations of this invitation we’ve been given to share in other ways of seeing and thinking. Anything that can be done to raise the profile of language as a reflection of cultural diversity is really important.”

Perhaps the last words should go to Marie Lacroix (Missinak Kameltoutasset) from Canada, who contributed the Innu word tshinanu, meaning ‘the inclusive “we” – all as equals’. “Our environment is the land, the forest, the plants, the insects, the animals, the water, the air and the human beings who are the stewards of the creator’s gift,” she says. “An interdependent circle of life. From generation to generation, our teachings say that the Earth doesn’t belong to us, but rather we belong to her.”

Something to keep in mind, perhaps, as we negotiate the next phase of our relationship with her.

For more on the living-language-land project, visit www.living-language-land.org