On a cold, grey January afternoon, I sit with Janice Pariat in a cafe in Delhi. She tells me how, a decade ago, when she was walking in a garden in the UK, she stumbled upon a little exhibition about Victorian women botanists. “I was so inspired and so taken by these unruly, wild women just leading the lives that they ought not to be leading at that time,” she says. This is when Evelyn, one of the main characters of Pariat’s latest novel, Everything the Light Touches, emerged in her mind. But it was only much later, during the pandemic, that Pariat found the quiet and stillness needed to write the book.

Pariat is a writer and poet based between Delhi and Shillong, the capital of Meghalaya, a state in Northeast India. She is an assistant professor at Ashoka University, where she teaches creative writing and history of art. Her previous novels are Seahorse and The Nine-Chambered Heart. In 2013, she received the Yuva Puraskar, a literary honour awarded each year by Sahitya Akademi (India’s National Academy of Letters) to young writers of outstanding works in one of the 24 major Indian languages. She also won the Crossword Book Award for Fiction for her debut collection of short stories, Boats on Land. Everything the Light Touches is the story of four people who undertake long journeys, each in search of something, their travels spanning four centuries and beyond. Shai from present-day India, a young woman raised in Shillong, who has been sent to Delhi to study and work, returns to her hometown and heads to a remote village. Evelyn, a young botanist, defies social norms in the Edwardian era and leaves England to travel to the wettest place on Earth in colonial India. Goethe, the German poet and scientist, leaves his courtly life in Weimar and voyages to Italy while he contemplates a new way of seeing Nature. And Carl Linnaeus, the Swedish botanist, documents his expedition to Lapland, armed with the task of finding and naming plants.

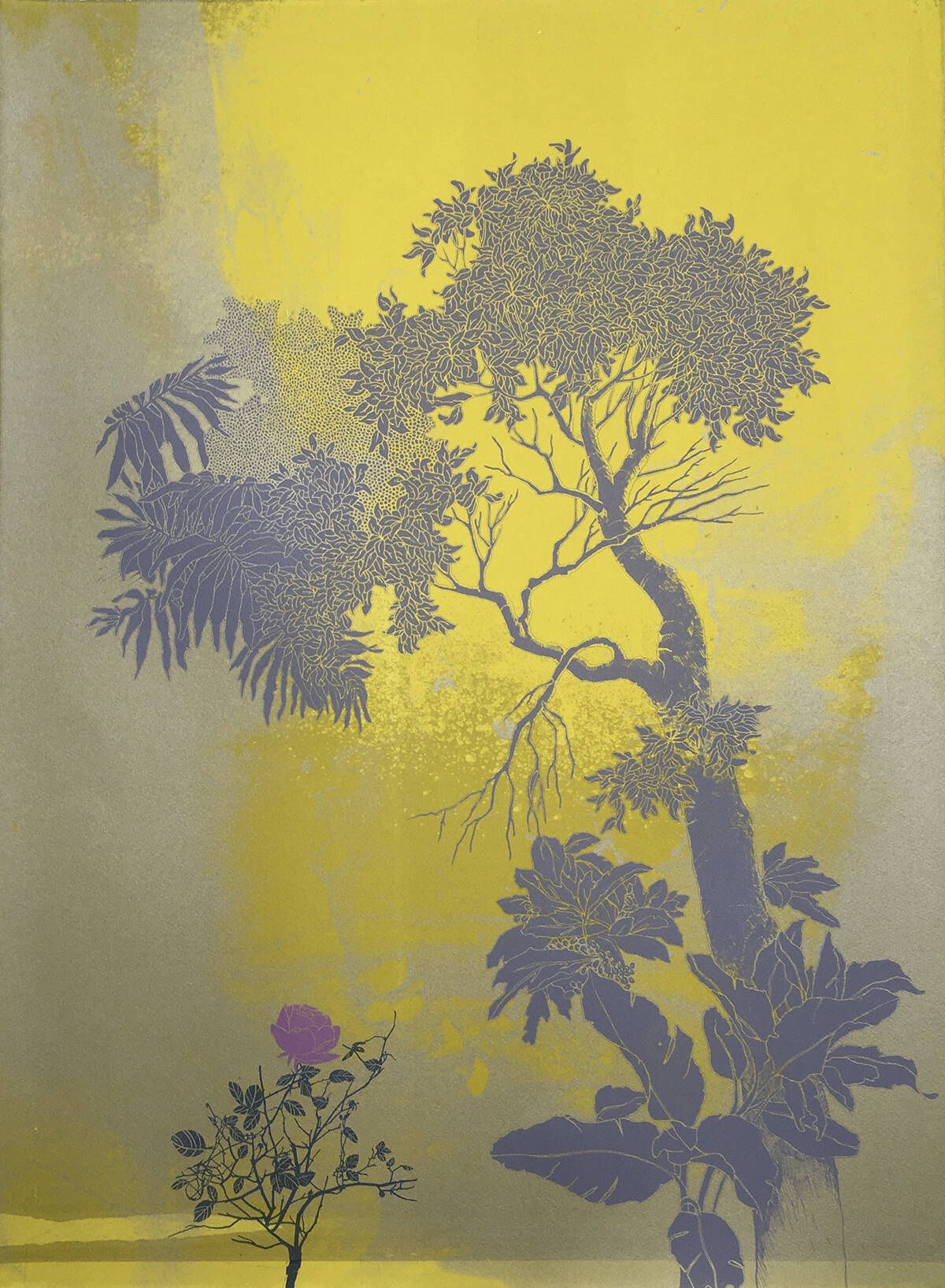

The book asks questions centred on our relationship with our planet. Why are we obsessed with objectifying the abundance that exists in Nature? Is there a more wholesome way to interact with it? Pariat tells me this is what lies at the heart of her novel. “It’s actually a deep tussle between two ways of seeing – the one that subscribes to a Linnaean view, that focuses on fixity, category and labels, and the other that’s more Goethean in nature, that calls for fluidity, untethering and unbinding of the imagination… But of course it’s a tussle, not as black and white. They are contentious, but entwined also.”

Some years ago, Pariat discovered Goethean science while talking to a friend who was studying at Schumacher College in England. Goethean science is an alternative, holistic way of looking at plant life, one that is based on patient observation, inculcating a sense of wonder and interconnectedness. Pariat’s curiosity led her to read more. And then she began to think of Goethe in resistance to the dominant paradigm, which was Linnaeus’s meticulous organisation of the botanical world. She explains that this rigid, compartmentalised way of studying Nature was a product of the Enlightenment era in Western Europe. “With the Enlightenment came this fervour to understand the world in a very particular way, in a very rational and orderly way that was filled with hierarchy. And this was a hierarchy that placed humans at the very top of this fabricated pyramid and viewed us as the darlings of creation. Everything else lay before us to be named, tamed, controlled and eventually hugely exploited: all that we see happening within the colonial project. And Linnaeus is very much a product of that.”

Resistance against hierarchy and order is one of the themes of the book. Shai defies her mother’s expectations of achieving conventional success and spends time with an Indigenous community protesting mining near their small mountainous village. Evelyn, who studies botany at Cambridge, questions the mechanistic approach of studying plants, and joins the Goethean society. “That’s what Goethe talks about in the book – object thinking, which removes us, distances us,” says Pariat. “We don’t see the world then as living, breathing objects with their own functions, agency and ways of being, from which we could learn and understand by holding ourselves back, by giving more space for the living world to take shape before us in a more organic way. A particular kind of understanding could grow through a different way of understanding – a world that is gentler, less intrusive and less impositional.”

Pariat calls her novel “a deeply political work”. The story brings alive the landscape of Meghalaya, its sacred forests, verdant hills, caves and streams, where the threat of extractivism looms large upon Indigenous communities. The book carries a strong motif of connecting with the larger world through movement and travel, what one of the characters calls “being more in the world”. It poignantly depicts the Nongiaid, a fictional nomadic tribe, and their disappearance after they are forced by the state to settle down. “The Nongiaid formed as one of these very important elem-ents that speaks very directly to this tussle between fixity and fluidity. They are the unsettled, wayward, wild, unruly and untamed that the Linnaean way of seeing is constantly trying to suppress, isolate, manipulate, tame, get rid of, and eliminate. This shows up in the larger context of our nation because you cannot speak of the Northeast, you cannot set a story there, no matter how wonderfully, beautifully, unnecessarily frivolous, without in some way alluding to this. That it is a region that is sacrificed so immensely to the larger nation-building project.”

Pariat recalls spending a lot of time outdoors as a child in Meghalaya and Assam. In the pandemic she returned to Shillong, rediscovering the forest and farms behind her house. This relationship with the natural world that she has so lovingly nurtured informs the tactile sense of place in Everything the Light Touches.

“We come from the moment that the universe is born. We don’t begin here and now. We have begun from the very, very instance that the universe began. When you see a story in that kind of vastness and continuity something changes in you and is placed into perspective. Something is humbled and you’re just wonderstruck and grateful that you exist, that you are miraculous.”

Everything the Light Touches is published by HarperCollins. For more on Goethean science see: tinyurl.com/goethean-science