Most of us have heard that making is good for our wellbeing, helping us to feel calmer, more reflective and more in control. But what is it about creating something by hand that can be so powerful?

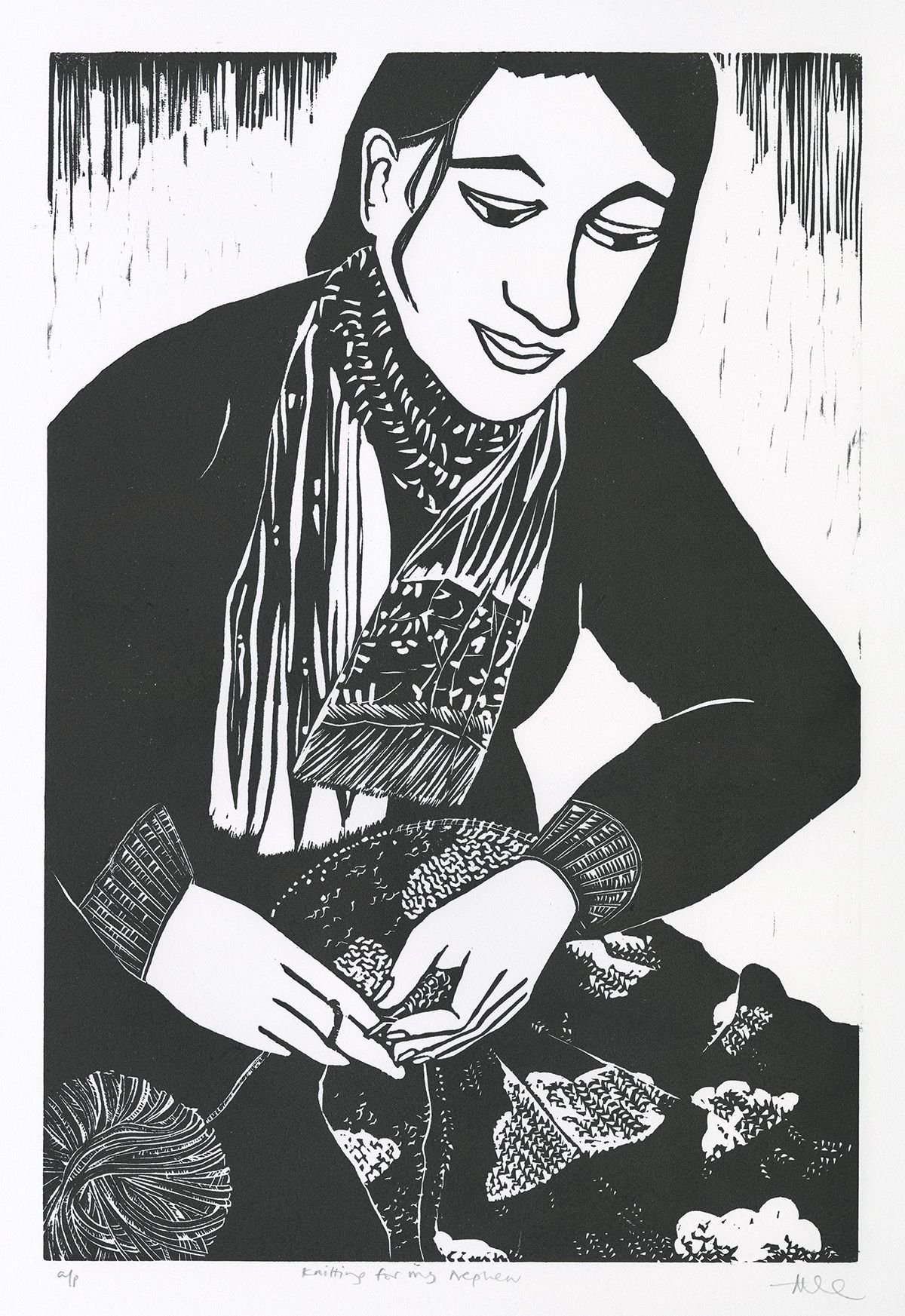

Crafting as therapy has come in and out of fashion. We have records of soldiers being taught knitting and basketry in hospitals, for example, where it was found that, as well as being an activity that passed the time, the process of making allowed the brain to learn something new and distracted the invalided soldiers from disturbing and intrusive thoughts and pain. Contemporary research shows the benefits of knitting for pain relief in a similar way.

The theory of many experienced occupational therapists is that learning crafts stimulates and develops cognitive function and promotes the orderly processes of thought, and can help us exert some control over the world – or at least over our own lives. That’s also why craft is so useful in schools: helping children who live in their heads too much, as well as the fidgeters who can’t sit still, to embody the mind, linking head and hand together.

Making offers a sense of purpose, which might also be rewarded with positive feedback when others admire your skill or inventiveness. For those who have been making for while, there may be a sense of flow when they are creating, an element of going into a zone of concentration where everything else becomes less important. The act of making also engages us in time for thoughtfulness, or what is often called mindfulness. If you are concentrating and engaged, you are less likely to entertain ruminative thoughts or repetitive feelings. Put all these together, and you have a sense of power over your environment, a feeling that what you do can make a difference.

Making can help to alleviate loneliness too, offering the opportunity to interact with others and improving social cohesion. People who might shy away from other forms of socialising often find that sharing a common interest and being able to look away and focus quietly on what their hands are doing allows them to be with others in a gentle way.

Arts and crafts are part of the fabric of our culture. They are invaluable in making rituals and ceremonies such as funerals and births impressive, memorable and unique. Part of the benefit of making is the sense of purpose inherent in this meaningful activity. Scholar Ellen Dissanayake, the author of Homo Aestheticus: Where Art Comes From and Why, points out that we are defined by anthropologists as Homo faber, the toolmaking animal, leaving our mark on the world. “The care or control required to fashion and embellish an important tool was like a metaphor for the care and control one wished to exercise in using it and the value one imbued it with,” she says. She goes on to talk about joie de faire, the joy of making, believing we are denying this to young people.

Dissanayake looks at making as a social necessity without which we can’t thrive. She believes that “someone acquainted with human evolutionary history must question whether our species can prosper if so many of its evolved abilities are not fostered and so many of its evolved needs are not met. Making is not only pleasurable, but meaningful – indeed, it is because it is meaningful that it is pleasurable, like other meaningful things – such as food, friends, rest, sex, babies and children and useful work – are pleasurable because they are necessary to our survival as individuals and as a species. A society that devalues making, and making important things special, forfeits a critical component of its members’ birthright.”

Making is not only good for us personally. It also has the potential to be good for the world around us. Betsy Greer, dubbed the ‘godmother of craftivism’ by a Greek newspaper back in the first decade of the 21st century, says: “The creation of things by hand leads to a better understanding of democracy, because it reminds us that we have power.” The sense of power is embodied in the act of making, in the ability to create something from nothing and in the sense of agency embodied in the choices making involves. “If you are feeling that things are out of control,” she says, “looking at something you have made and the choices it involved can be a talisman of strength.”

Greer’s understanding that you can use craft to create the world you want to see stems from talking to her grandmother, who knitted hats for newborns in the hospital where she volunteered. “She would have never called herself an activist,” Greer explains, “but boy, did she make the world better with her own two hands. Quietly. Deftly.”

Greer has spent much of her adult life investigating how making things with our hands can improve our own lives, the lives of the people in our communities, and the world at large. Her books include Knitting for Good! and Craftivism: The Art of Craft and Activism, and she is the creative force behind the stitch-focused community projects Dear Textiles and You Are So Very Beautiful. (See page 43.) She calls this work ‘craft-ivism’, which she defines as being “as much about fighting the bad things we tell ourselves as it is about fighting the bad things of this world. It is about healing ourselves as we make, and then maybe healing the world with the things we produce.”

Making is such a huge part of all our lives that it’s astounding that it is becoming less and less present in schools – over the last 12 years, 60% fewer young people have taken Art and Design GCSE. The ripples of this decline are being felt in society, with disruptive behaviour in schools reaching unprecedented levels and an epidemic of attention deficit and anxiety. In our book Intelligent Hands: Why Making Is a Skill for Life, we argue that craft is an important part of the solution because making is good for us. Using our hands benefits our cognitive development, improves our mental agility and can have a positive impact on our mental health too. In his foreword to the book, Jay Blades, the British furniture restorer and award-winning presenter of BBC TV’s The Repair Shop, writes: “In a world facing a mental health crisis, economic challenges and possible environmental collapse, I truly believe that craft is an important part of the solution, and that the first change is embracing our own shared humanity as makers.”

Intelligent Hands: Why Making Is a Skill for Life, by Charlotte Abrahams and Katy Bevan, is published by Quickthorn. www.quickthornbooks.com

Join the authors and Daniel Carpenter, Director of Heritage Crafts, at 6pm on 8 February 2024, at The Dartington Trust Shop. www.dartington.org