Caleb Parkin’s poetry has the wonderful quality of showing us how magical the more-than-human world really is, and then playfully encourages us to re-evaluate our relationship within it. One way he does this is by switching pronouns, going from the individual ‘I’ to a more ecologically minded ‘we/us’. “For me,” he writes, “much ecopoetry relates to this tr/icky balance of being-with the nonhuman world. So yes, there is always a playfulness – but it’s a frivolity with intent.” He urges us to look closer and to decentre the human, in order to understand that the world is, to quote Thomas Berry, a “communion of subjects” rather than a “collection of objects”.

Pools, ponds and reflected forms in various configurations feature strongly in his new collection Mingle. For example, in ‘A Pink Sink’ and ‘Waterlily House’, the lines spool one way until reaching a kind of nexus, or reflection point, and then spool back out in the other direction, with tiny changes that expand the meanings, challenging our understanding.

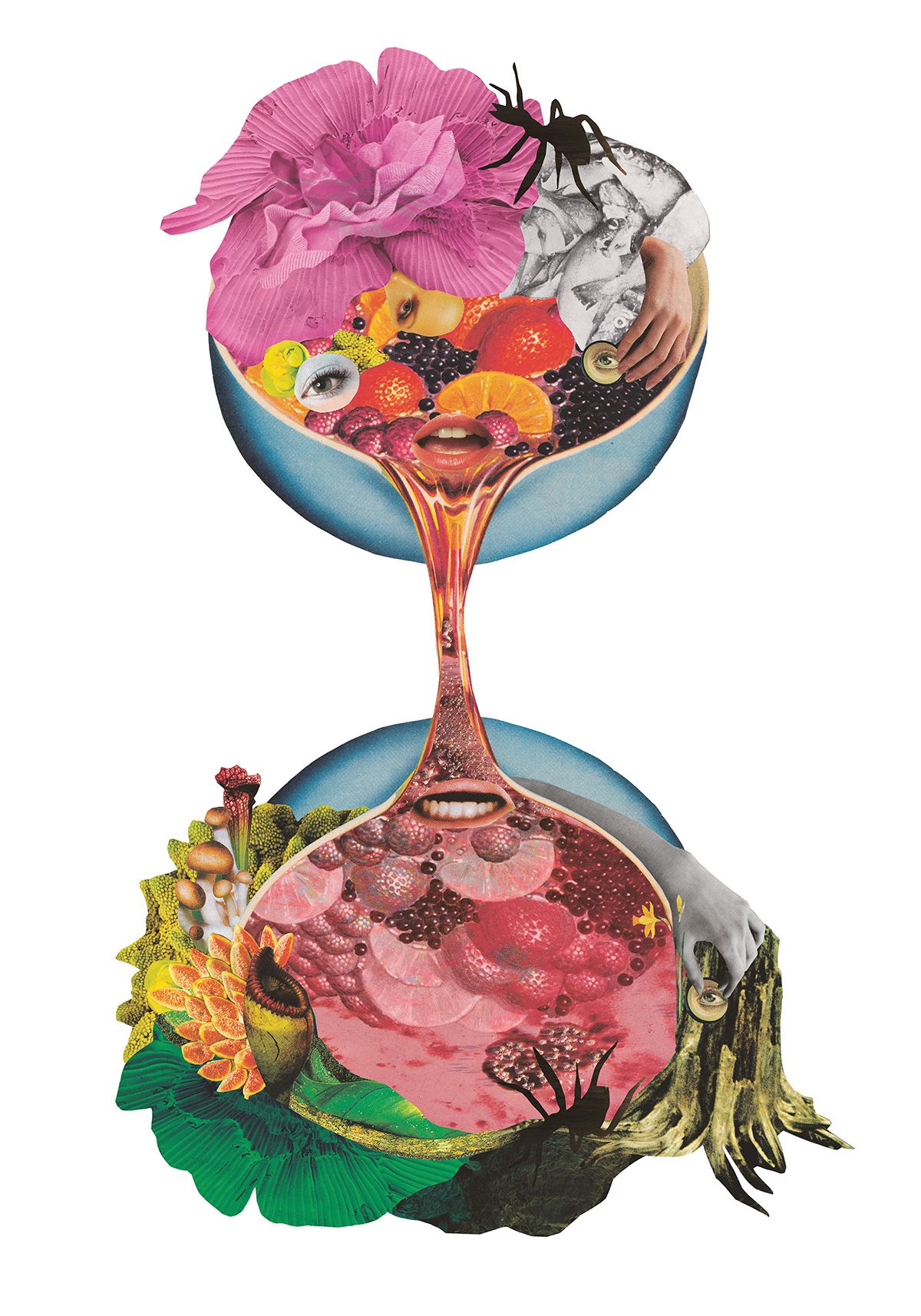

Parkin enjoys Donna Haraway’s use of the word ‘bumptious’ to describe the nonhuman – its unruly, “unapologetically uncontainable” quality. This is why, when you read his poems, you’ll spot elements from queer culture, swaps in persona, changes in register and style, and a smattering of references to popular culture. No surprise, then, that cover artist Georgia Robinson’s collage work “with its fabulations of human and nonhuman elements” so suits Parkin’s work. Their collaboration began when he sent her some key poems from the new book, and she sent draft collages in return. He wrote his poem ‘A Pink Sink’ in response to her work, and this now closes his book Mingle – another reflection: “The artwork and the poem which inspired it, itself inspired by the poems between, reverberating back and forth,” he writes. “Delicious.”

Read the full interview with Caleb Parkin below.

Waterlily House

Victoria boliviana, Kew Gardens

By the door, three-foot leaves capsized:

their vascular undersides, umbilical stalks;

through wrought iron spirals enter

in this thick air, where lily pads hover

on a pool, circled in white concrete.

They surface, unfurl, spread pinkly –

spiny fogs that roil across the pond’s

black membrane. The glass smirched with

plant-breath; climbers viscerate

from white iron Os on the rafters.

We circumambulate this cell:

how polished, staged, the way all bodies

are becoming. From within, you cannot see

those leaves, their palms pressed out

on greening panes, how

they long to permeate the skin.

We long to permeate this skin,

its greening panes. How

our leaves, their palms, press up,

are becoming from within. You cannot see

how polished, staged; the way our bodies

are circumambulated. This cell,

from the white iron Os of these rafters:

plant-breath. Climbers viscerate

black membranes on glass smirched with

spiny fogs that roil across our pond.

We surface, unfurl, spread pinkly

on our pool, circled in white concrete

in this thick air. We’re lily pads, hovering

through wrought iron spirals. Enter

our vascular undersides, umbilical stalks,

these doors – three-foot leaves, capsized.

St Francis Christens the Animals in Notre-Dame, on Fire

Come forward, Brothers, Sisters all, to this font,

this pool of Sister Water – who is very useful

and humble and precious and chaste – and chase

her we must, for there is not enough of her

to extinguish this roof. Sisters, Brothers: bring me

your pups and younglings, the luminous green

commas of newborn chameleons; the translucent

spheres of the wormy platypus. I Christen them

amongst indoor asteroids, Brothers; altared ash,

Sisters. Throw me your babies, your bulge-eyed

chicks, pink like roast ortolan. Fling your lungfish,

I will try to catch them. And, if water is already

their element, I will raise them up to Brother Wind

and bless them in air. Beware the failing beams,

Sister-Brothers: the nave’s fall. This font contains

Amazon, Yangtze, every river dammed to never

delta into epiphany. Hand me your infant pangolins

and I will sprinkle their scales like morning cloudburst,

my arm a dwindling canopy. This is my Canticle: my can-

tickle-tickle under those crusty armpits of your bonobo

bambinos. (Oh no, not now, Sister-Sisters – not that,

thank you.) Brother-Sisters, of course the frilly larvae

of axolotl are kin: all are in this pool of time, evaporating.

Can you see me through the smoke, Brother-Sisters?

Can you pray with paws and wings to Sister Water:

though precious and chaste, she cannot save this roof.

For, if He so wills it, this roof may resurrect again;

now pray to Father Capital, with all your claws and fins.

A Pink Sink

after Georgia Robinson's cover artwork

on our back garden wall brimming like a punchbowl

its rogue eyeballs raspberry globules fruity polyps

a syrupy rainwater reduction a gastropoda aperitif

low self-seeded fascinator its plinth a neck slurps

like gum from a rubber sole and below

ground a mucky mirror viscous like vintage soup

in this slow-churn reflection ants making their

underground deals the tuber-nodes and grub-lumps

heaving up bodily this sink like the ones at after

after parties where sometimes I’d see at bowls

at basins a perimeter of lime-green friendly

bacteria swelling their flagella in 4/4 a wave

of invitation to flush myself to dive into

the greening water table in full-throated harmony

with the pitcher plant mouths of the subterranean

with the pitcher plant mouths of the subterranean

this greening water table in full-throated harmony

of invitation to flush ourselves to dive into

bacteria swelling our flagella in 4/4 a wave

at basins a perimeter of lime-green friendly

after parties where sometimes we’d see at bowls

heaving up bodily this sink like the ones after

underground deals we tuber-nodes and grub-lumps

in this slow-churn reflection ants making our

ground a mucky mirror viscous like vintage soup

stretching like gum from a rubber sole and below

low self-seeded fascination this plinth a neck slurps

a syrupy rainwater reduction a gastropoda aperitif

its rogue eyeballs raspberry globules fruity polyps

on our back garden wall brimming like a punchbowl

Full interview with poet Caleb Parkin by Poetry editors Rachel Marsh and Briony Hughes

How would you describe your work to someone who doesn’t read a lot of poetry?

My poems often explore our relationship with the more-than-human, through the lens of queer ecologies. That means the intersection of thinking, writing, and making – related to ecology, gender and sexuality. I deploy aesthetics drawn from queer culture, camp, persona, a mixing of registers, and mixing-in popular culture or ‘Nature-in-culture’ as I see it. All of which feels perfectly ‘natural’ to me, even when it seems surprising to others! Because, perhaps, of the rarefied ways in which we think of both poetry and ‘Nature’ as a pristine entity, which exists elsewhere, or ‘over there’ – rather than right here, right now, in all its grubby, bumptious glory.

Your work has a wonderful quality of being able to make the world magical.

I’ve been reading and thinking about Donna Haraway’s work lately and love the word ‘bumptious’, which crops up in her writing about the nonhuman. It means (OED) “irritatingly self-assertive or conceited”. Unapologetically uncontainable! A helpful reminder to decentre the human and live in a world that is, to quote Thomas Berry, a ‘communion of subjects’ not a ‘collection of objects’. To look closer.

I love your playfulness with pronouns. How is this important in your work?

There are lots of pools and ponds in Mingle – and a sense of drowning in a reflection... One of the looking-glasses I’d like people to ‘go through’ is of the individual ‘I’ and the ecologically collective ‘we/us’. This is a potentially uncomfortable process. For me, much ecopoetry relates to this tr/icky balance of being-with the nonhuman world. So, yes, there is always a playfulness – but it’s a frivolity with intent. I don’t always know what I’m up to until later on. You can feel when there is something interesting beginning to mesh during the generation of a poem – and it can feel ‘good’ and ‘uncomfortable’ at once. Learning to follow that icky and/or lovely feeling when it arises during a writing session is vital to keeping a poetry practice (and the poems emerging from it) alive.

How do you use form?

I’m not a super-formal poet in terms of rhyme and rhythm, although sometimes I’ll work with these where it feels the poem’s subject would suit it. Often I find that the poem wants to escape from any set forms fairly quickly – unruly entities that they are.

That said, I love poetic form and what words can do on the page. I’ve been trying out various specular poems where the lines run one way, then the opposite way after the ‘hinge’ or – perhaps – waterline. In the second half I make small changes, so that it reads differently and new possibilities emerge for reading the work.

I’ve also enjoyed playing with reflected forms in the collection. Each poem – like a pond/pool – is a world, then a book is its own world too. Some poems are split across the page – and then meet, mingle, in the middle. My hope is readers might flick through and see these echoes and mirrors, inviting them to think about the connections between those two poems and the ideas they’re exploring.

How did you start working with your cover artist Georgia Robinson?

It immediately struck me how Georgia’s collage work – with its fabulations of human and nonhuman elements – absolutely suits my poetics. I sent her a selection of key poems from the book, and she created draft collages in response. We were both keen on this overpouring bowls design, in how it reflected the themes of the book – toxicity, time, deliciousness/disgustingness. I wrote ‘A Pink Sink’ in response to Georgia’s work. We have – unsurprisingly – a pink sink on the garden wall, which has filled with rainwater and self-seeded pond weed, water snails, and who knows what else. This little pool became the closing poem of the book – and a coda, or ‘rounding off’ of themes. The artwork and the poem that inspired it, itself inspired by the poems between, reverberating back and forth. Delicious.

It’s an incredible privilege to commission cover artwork. Georgia’s artwork will be (watch this space!) turned into some clothing for when I read from the book. I hope there’ll be some themed cocktails too – and themed DJ sets. (I moonlight as one.) We can call this marketing, if we wish. Or perhaps it’s creating a whole vibe around the book, to invite people in – to dance, to drink and, maybe, to swim.

Caleb Parkin, Bristol City Poet 2020–22, was a guest on BBC Radio 4’s Poetry Please and has had poems in many publications including The Guardian. His debut, This Fruiting Body, was longlisted for the Laurel Prize. Mingle, his second collection, is out in October 2024. He is a PhD researcher at University of Exeter with RENEW Biodiversity.