I am curious about everyday phrases people use when they talk about their working lives: phrases such as “work/life balance” and “work to live, don’t live to work”. They suggest that work and life are two distinct realms, and that real living only happens outside work.

With the pending increase in the UK state pension age, it could become the norm that adults spend up to 50 years of their life in work. (The UK state pension age is currently 66 for both women and men, but it is due to increase to 68 between 2044 and 2046.)

So far I’ve spent my adult working life in law, a career I set my sights on as a young teen. I was drawn to employment law, firstly because it’s about people, but also because of its shape-shifting nature. A key focus in employment law is what’s ‘reasonable’ (and this changes, depending on all the circumstances), and it continually evolves to reflect changes in our social, economic and political landscape.

During my early career, I mainly advised large commercial employers, including in the shipping industry. But I became increasingly aware that the real beneficiaries of my efforts were the shareholders of the businesses I represented, with little positive impact felt by the people who worked there. My work started to feel misaligned to my personal values, and this eventually led to my co-founding a new law firm in 2014.

We set up our firm to work with employers seeking to make a positive difference in the world, to help them navigate the complexities of employment law in a way that reflects their purpose and values.

An unwelcome catalyst for deeper scrutiny of my work came in 2021. My father died unexpectedly at the age of 73. Even during his last few days, with his organs rapidly failing, my father’s love of life shone through. Struggling to speak, he still wanted to make us laugh and conveyed his love to each of us in our family. My father was so open-hearted, kind and funny, naturally seeing the joy in life. He’d always radiated a contagious glow of warmth.

Along with my mother and brother, I was with my father when he died. I’ve never before been with anyone at the end of their life, and whilst we know that death comes to us all one day, seeing it so close with someone you love so dearly was a stark realisation.

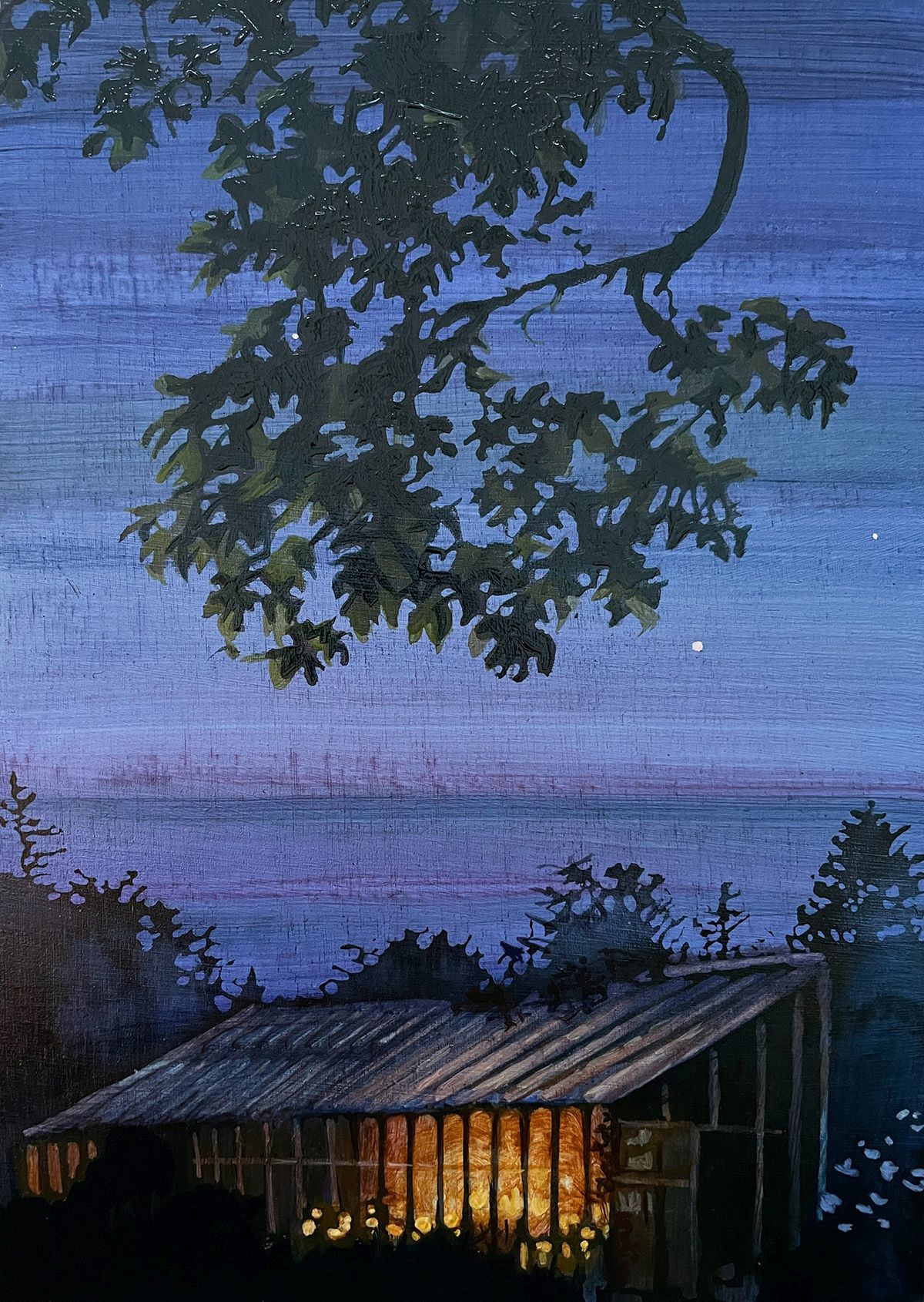

During the time of my early grief, the closest I found to solace was in my greenhouse. Perhaps this was partly because greenhouse gardening was a hobby that my father and I shared. There, I reflected a lot about life, death and my father’s legacy. I also listened to various books that spoke to those reflections. One was Oliver Burkeman’s Four Thousand Weeks, the title referring to the average life span. The book’s premise perfectly captured my growing realisation that life on Earth is finite (and, in turn, so are human relationships). It’s making peace with that realisation that enables us to fully embrace life as a gift.

Through my grief journey and reflecting on the finitude of life, I started to feel a further shift in the direction of my work. My work has remained focused on purpose-driven employers seeking to make a positive impact in the world. But as well as wanting the organisation to succeed in its purpose, I’ve had a growing sense that the employees who deliver that purpose are entitled to meaningful work that enables them to thrive as human beings and enriches their lives. This requires organisational life to be approached in a way that genuinely meets everyone’s needs.

Employment law is intended to achieve a balance between the needs, rights and obligations of employers and employees, but this is often seen as a balance between competing interests, employer versus employee. Balance can be about holding all interests in balance, a relationship of collaboration for a shared purpose.

Weaving an organisation’s purpose and values through all of its frameworks, decisions and activities lays a strong foundation. However, so much more is needed for someone’s experience in work to truly enrich their life.

Over the past couple of years, I’ve increasingly immersed myself in new discovery, through learning and collaboration, to give more depth to my work and ‘fill the gaps’ within the employment law framework. This is partly to keep joy in my work ignited – after all, who knows if I’ll have more or less than the ‘four thousand weeks’ – but I also believe that the changing world of work (accelerated post pandemic) needs a more holistic practice of employment law.

This includes, for example, re-imagining and reframing some entrenched models and processes in the workplace. One of my recent collaborations has been using the ‘Cards for Life’ tool, designed by Tom Mansfield*. Our intention is to re-imagine the more traditional approach to HR processes (which can feel mechanistic) through a more regenerative lens. This is on the premise that as humans we’re part of Nature, so we need to live in accordance with natural principles to truly thrive.

I hope employment law practice generally evolves to support a move away from the extraction paradigm in the workplace. The traditional employment deal is this: extract all value from an employee’s time, skills and experience in return for their remuneration package. But if we genuinely see work as part of life – and understand that life itself is a gift – this clearly needs to change.

If life is a gift, and a finite one, shouldn’t we do our best to make work a meaningful and enriching part of it? There’s a positive ripple effect if the work is done for an organisation whose purpose is to have a positive impact in the wider world.

Life really is too short for work to be at best a tolerable part of it.

Society’s challenge is to make work part of life’s gift.

*Editor’s note: Tom Mansfield, who created the Cards for Life system, is a contributor to the next issue of Resurgence & Ecologist (March/April 2025). www.paleblueperspective.com/cards-for-life