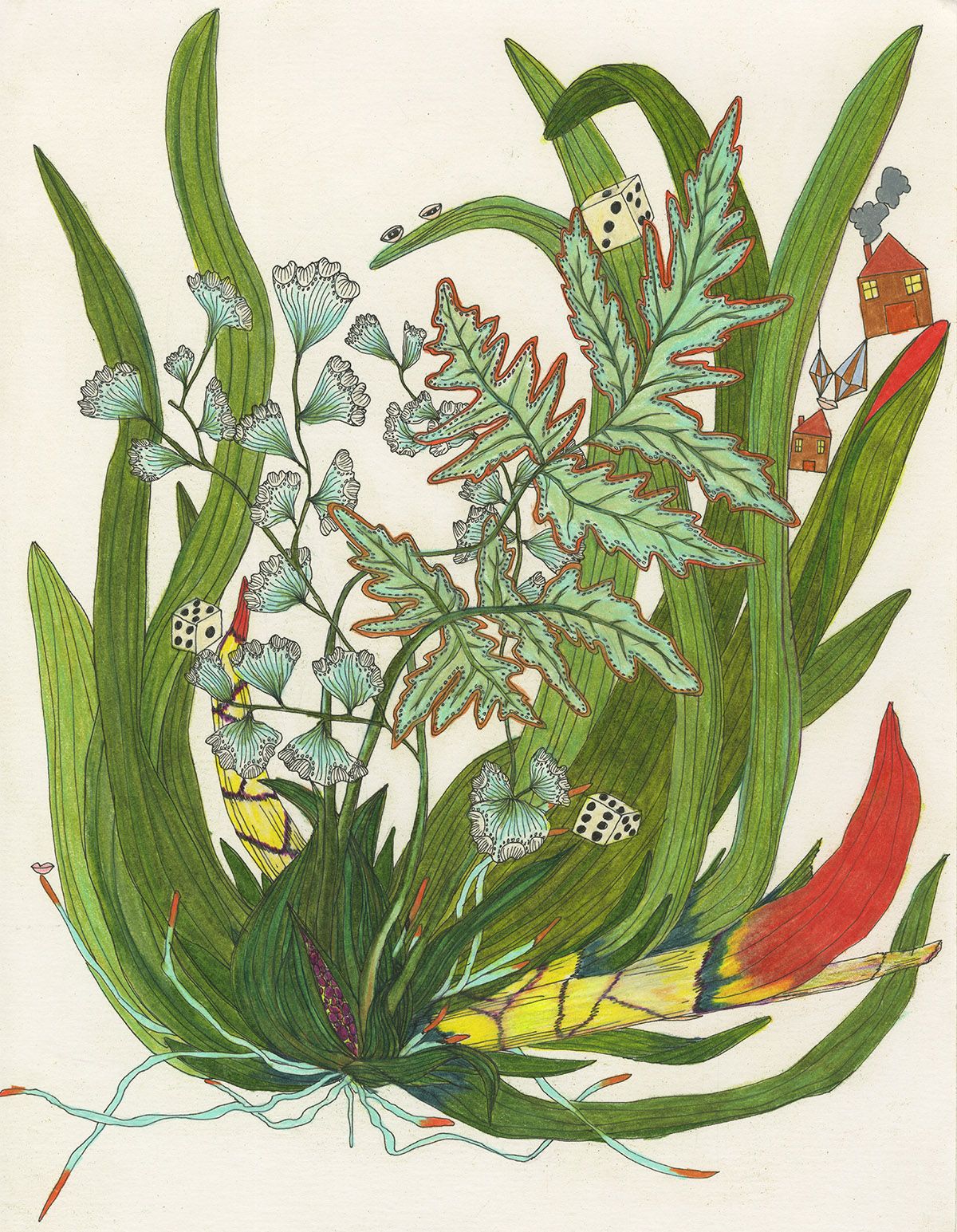

I remember crouching beneath the gulmohar tree, amidst the crisp layer of fallen leaves and the patchwork carpet of crimson petals, searching for green-gold treasure. Fallen buds. They had to be just right, the five fused sepals just beginning to blush red at their seams, and taut with the swelling petals within.

If too dry, the petals would crumble in my young fingers as I tried to open them, and if not mature enough, they would be impossible to peel open. Satisfied with a harvest of five or ten buds, I would run to find my human friends. Others would have brought other garden finds – the pods of Mexican bluebells, or the pungent fruits of the Persian lilac tree. An afternoon of botanical games and revelry followed. And here are some of those games…

Peel away the spongy outer sepals of the gulmohar (Delonix regia) buds and the fleshy red petals to reveal the many curved stamens. These can be interlocked in ‘battle’, with the player who succeeds in detaching the anther of her opponent being declared the winner. The seed heads of the chipku grass (Setaria verticillata) are sticky, like Velcro – chipku means ‘sticky’ in colloquial Hindi – and make perfect darts to throw at each other in a spirited game of tag.

The fan-shaped flowers of Petrea volubilis twirl through the air as they fall, and players compete to see whose flower will reach the ground first. The young buds of the tulip tree (Spathodea campanulata) are filled with a pungent-smelling cloudy fluid that surrounds the developing petals. Deftly pierce the narrow tip of the bud with your fingernail, and you have a loaded water-spray to aim at your friends, or a felt-tipped marker with which to draw evanescent patterns on the ground.

Many flowers lend themselves to making wreaths and garlands: you can thread Ixora flowers (Ixora javanica) and the flowers of the Rangoon creeper (Combretum indicum) by inserting the neck of one into the throat of another. A variety of seeds lend themselves to being mancala pieces – we always played with the scarlet red seeds of the coral seed tree (Adenanthera pavonine). Yet plants were more than playthings: they quickly became playmates. The games we played relied on the specific characters of specific plants – in other words, you had to get to know the plant before you could play with it. You had to make friends.

Befriending plants as playmates was how I came to love them. This went far beyond anything academic inquisitiveness could uncover, or what horticultural experimentation would later reveal. This was a foundational familiarity, one that also constituted a way of knowing. Now I think: could there be a playful ecology? Who are our fellow participants and playmates, and what is our playground? Can playing shift the way we see Nature and our place within it?

Through play, gradually my playmates became more familiar, more known. Like how the gulmohar tree has one aberrant petal, paler and more patterned than the other four. How the seeds of the laburnum (Cassia fistula), which became mancala pieces when others were in short supply, are each encased in their own leguminous compartment, sealed in with sticky sweet tar. Extracting enough for a game could take a whole afternoon.

Later I would be introduced to other playmates through the plants – the butterflies and moths who read the gulmohar’s aberrant petal as a landing sign; the ants who carried away the tulip tree buds; the tiny beetles who tried to eat the laburnum pods but were deterred by the same sticky sweetness that caused the jackals to relish them. To the theorist who says that it is through play that children learn to be a part of society and are socialised, I would reply that through play I became naturalised. I learned my place amongst the trees and flowers and birds and beetles.

Play as a way to reconnect

In life I would come to recognise this playfulness many times, connecting me to playmates in space and time. The ancients of the Sanskritic cultures designed gardens and natural spaces for play, detailing how to arrange flowers in pleasing ways, how to distil perfumes, and how to make colours and paints from plants and ores. In a 12th-century compendium, the chapter on woodland sports, arboriculture and garden design is titled ‘Vanakrīdā’ (‘forest play’). Play in these contexts is not infantilised, but taking many forms it becomes friendly play, lone play, love play, thrilling play – encompassing the entire range of human emotion brought into contact with many non-human playmates.

By playing mancala with those bright red seeds of the coral-seed tree, I unknowingly linked myself to my Bronze Age ancestors, who carved out petroglyphs in solid rock to perhaps play a different version of the same game.

From the Aravalli Range of north-western India to the Arabian Peninsula to the Pacific Islands and Oceania, the act of ‘sowing seeds’ on a mancala board has united us with both Nature and each other in ecologies of play. That same image of sowing seeds, though, conjures dark visions of cotton plantations in North America, where enslaved Africans played mancala as a way to reconnect with their homeland through plants and through play. By ‘sowing seeds’ in play they reclaimed the vocabulary of exploitation but also enacted hope and prepared for a future in which planting and play would both be carried out on their own terms. Here playfulness becomes the tool to imagine alternate realities, to create other worlds.

In other contexts, botanical playmates connect human playmates across geographies and cultures. In the simplest act of gathering plants – the search for the perfect bud or leaf – I enact a game of children in Odisha, Patar Anati (‘bringing the right leaf’), predicated on the players’ ability to find and bring a particular leaf specified by their competitor. The game is curiously reminiscent of the story of the fox-turned-maiden Tamamizu from Japanese lore, whose mistress arranges a playful contest to see which of her friends can find the most perfect autumn leaf.

This story is particularly interesting, for characters seem to travel effortlessly between the human and natural worlds, almost as if imploring the reader to breach the divide between the two. Perhaps play not only helps us create other worlds and realities, but also shows us that they are close at hand (closer than we dare think), access-ible through the simplest act of gathering a leaf.

But what do any of these disparate, playful strands have to do with ecology?

In many ways, Indigenous ecologies are inherently playful. To speak of a playful ecology is to speak of a relationship with humans and non-humans which is open to unstructured imagination, allows for pretend and make-believe, and in the process creates worlds where the boundaries between Nature and culture can be effectively blurred. What else do the ancient poets and storytellers, farmers and philosophers do, if not this?

In the ‘real’ world, I may not be able to speak with the gulmohars or the ants gathering around the tulip tree, but the play-world allows me to shed that constraint. Play makes space for enchantment, where, Timothy Stacey of Leiden University writes, ‘non-human beings demand our attention and call on us to act’ – and to interact.

In the play-world, knowledge suddenly becomes two-way, two-eyed. It is not me observing Nature, but Nature demanding my attention. I need not just look at Nature, I can become it – I am the same as the jackals at the laburnum, or the breeze in the Petrea vine, and this creates new metaphors for understanding. Play is the most powerful mode of this embodiment, fostering mutual understanding and love, shifting our ways of thinking and knowing from being individualistic to being biospheric.

Effectively, playful ecologies are emergent states arising from the ongoing interactions between diverse play-worlds. These play-worlds unite the human and non-human in multispecies entanglements that broaden and deepen the ways in which we see ourselves in/as Nature.

Play needn’t be intentional in an ecology of play – as in a study by Hannah Hogarth of University of Bath with children and an urban park in the UK: ‘The grass in the park grew with the rain and the sun which challenged anthropocentric understandings that humans are responsible for growing and protecting plants, deciding who lives and who dies. The teachings of grass are lessons in entangled futures.’

Today, though, we seem far removed from these entanglements, caught as it were in trappings far less metamorphic or benign. We have forgotten, somehow, to play as Nature or play with Nature – only to play in Nature, if that. Perhaps the Sanskrit poets and enslaved people and Tamamizu already experienced these entanglements, more directly and intimately than we do today. And perhaps, if we let ourselves, the way to kindle again that embodiment and that intimacy is simply to relearn to play.