IT IS BELIEVED that the Kamasutra, the Indian handbook on sacred sex, was written by a celibate monk, Vatsyayana. He conducted extensive research to find out sexual types, behaviours and attitudes to determine the levels of sexual fulfilment among men and women. The book has stood the test of time, and it is still considered to be the most comprehensive and thorough study of erotic love anywhere in the world.

The Kamasutra should be read in the Tantric tradition of India where union between man and woman is a door to cosmic and divine union. The intimate ecstasy of physical love is a way to experience the deepest and ultimate joy of being in love with God.

Here, the Indian philosopher Chaturvedi Badrinath captures the essence of the Indian view of sexuality where there is no division or dualism between the physical and the spiritual.

– Editor

THE KAMASUTRA IS the product of a civilization which had set out to understand human life in all its expressions. The quest of pleasure and happiness, which included sexual pleasure, was a subject of inquiry in the Upanishads, the ancient texts on Indian philosophy. Forty long chapters are devoted to it in the great epic of Mahabharata. And it is there most of all, long before the Kamasutra, that human sexual impulse is investigated systematically. But there was in all this a certain method of understanding. It is not until that method is understood that the various Indian views of human life and relationships could ever be understood, the relations between man and woman above all.

Of the many attributes of that method of understanding life, we need concentrate here mainly on four. Firstly, every person wants to understand his or her experience, and not just go through it without making sense of what one is experiencing. Understanding is, therefore, experiential: not merely intellectual. The problem is one tends to fragment one experience from another, and then seek to understand it; which, of course, is impossible, for the attributes of a human person are interrelated in a way that one flows into the other, and can be understood only in their togetherness.

Secondly, the method shows the natural inner unity of all human attributes. The physical body is not separated from the mind; nor are they separated from emotions and feelings. In their integral togetherness, they constitute the life force. The human species is not separate from nature; the five elements and the material and the spiritual are not two separate domains either. The physical and the material, as forms of energy, are also the spiritual, and equally worthy of reverence. The human body is as sacred as the spirit. This method is a striving towards understanding the self as the world, and the world as the self.

Thirdly, the method is to show that life is to be understood, and lived, paradoxically; for human life is paradoxical. The paradox of having is that the more one has, the greater is one’s discontent. The paradox of pleasure is that unrestrained pleasure kills itself: in other words, self-restraint is the very first condition of pleasure. The paradox of intimacy is that distance is the first condition of intimacy: the intimacy in which there is no distance turns very soon either to resentment or even to hatred. The paradox of sexual pleasure is that all those conditions which create sexual pleasure and happiness lie outside sexuality. The paradox of self-interest is that the only way of serving one’s self-interest is to serve the interest of the other. In other words, the pleasure and the happiness of the other is an essential condition of one’s own pleasure and happiness. The paradox of self is that without the other, the self will be inconceivable. And, above all, there is the paradox of limits, which consists in the fact that one becomes aware of one’s limits only by transgressing them: there is no known way by which one can know one’s limits in advance.

Fourthly, the method is to show how everything in human living is a function of ‘proper place’, ‘proper time’ and the ‘proper person’. These three must always combine in order to discover the meaning and beauty of life and relationships.

If we read the Kamasutra in the light of the four main attributes of the Indian method of understanding the human condition, we will get a very different picture of that work than without them.

TO THE AUTHOR of the Kamasutra, the body is as sacred as the spirit; sexuality in all its concrete forms as worthy of reverence as the spiritual. They flow into each other, as energy, to create the joy of life. To separate the two, under the wholly erroneous notion that one is gross and the other refined, one at a lower and the other at a higher level of consciousness, is from the very start to do violence to human worth, and thus do violence to one’s self. In brief, joy is not to be separated from reverence.

It will be equally erroneous to separate the physicality of sex from the erotic. Without the erotic, the physicality of sex is empty. To the body belong the sensations; to the mind and to the heart, feelings and emotions and sensibility. Sexuality, in order to be experienced and not just sensed for a little while, is suffused with the erotic. The togetherness of man and woman in a wholesome relationship requires first of all a wholesome relationship with one’s own self, in which any one human attribute is not wrenched from the others and then made the sole basis of one’s life. The art of making love would require, even in its own terms, cultivation of a much wider area of sensibility, such as music, dance, poetry, literature. And that is what the author, Vatsyayana, suggests in the very first pages of his Kamasutra.

Indeed, his list of the arts to be cultivated by a man and a woman, as essential to the fulfilling experience of kama, is so very long that one might feel discouraged in ever hoping to be a successful lover. It includes, as parts of the erotic, for example, knowledge of architecture and house-construction; knowledge of metals, of jewels and precious stones; of magic and creating illusions; and even the knowledge of bookbinding. At the first reading, this, coming from an acknowledged master of the erotic, may seem wholly absurd. For, what is being demanded of a man and a woman, before they can experience the joy of their sexuality, is that they should also be architects, metallurgists and magicians.

Vatsyayana is doing nothing of that kind. In reading a text, any text, one should not be too literal. A text is always suggestive. It is only that Vatsyayana wants us to be aware of the truth of the paradox of sex, that the conditions of a satisfying sexual union of man and woman lie outside sex. Sex, as energy, and primarily that, requires at the same time the flow of other forms of energy, without which it will diminish — and die.

Moreover, language is also of importance. A word, in denoting something, is saying much more than it denotes. Therefore, the feelings it will create will be different, depending upon the context in which it is being used. In one context, a word may denote something crude, something repulsive; in another context, the same word will be immensely exciting, indeed an essential aid while making love. Therefore, Vatsyayana shows the importance of uttering certain words, and certain sounds, when man and woman, in embrace, are flowing into each other. They are creating magic for each other in those moments. And the erotic is magic; not in the sense of conjuring up something that does not exist, but in the sense of marvel, astonishment and wonder. When there is no magic in the togetherness of man and woman, and no poetry, sex is lifeless.

There is another characteristic of the Kamasutra. It persists throughout the work. First of all, men are said to be of different types, depending upon the length and thickness of their linga, or phallus. Similarly, women are described differently, according to the varying depth of their yoni, or vagina. Vatsyayana then suggests that there are, accordingly, nine types of union between men and women of different proportions. Besides, there are nine types of union, according to the varying strength of passion; there are men, and likewise women, who have small, middling or intense passion, by temperament. The kissing is said to be of four types, depending on whether the kiss is a light, passing, brushing, or deep, intimate, throbbing kiss. The embrace, and the pressing of the thighs, is also of different kinds, each given a name. There are sixty-four different positions that can be taken in the act of making love, all with different names.

So far as making intricate distinctions is concerned, there is evidently here a delightful playfulness. When there is no playfulness in sex, it quickly loses much of its charm. There is in the Kamasutra a curiosity, about the possibilities of the body and the mind, and also about their limits. But this curiosity is playful. Fearing that some men and women may take him far too seriously, in trying, for example, many, or all, of the sixty-four positions, Vatsyayana, after describing them, immediately adds, somewhat laughingly, that merely because something could be done, that is no good reason for doing it.

This playfulness is in evidence, too, when the Kamasutra proceeds to suggest many practical ways of seducing a married woman. One should first know whether a married woman is approachable, and what are the signals she gives, there always being the possibility that the man may misinterpret some of those signals. What are the types of woman whose assistance may helpfully be sought, what are the circumstances in which a married woman may be easy of access, and what are the ways in which the man should proceed on his delicate mission? All these questions are gone into, with a thoroughness that is quite astonishing. What Vatsyayana is suggesting is, that if a man feels compelled by his passion to seduce a married woman, he should do it competently, and not bungle it, which would be disastrous. The seduction of a married woman has been a universal experience, in all ages, at all times, and a universal theme of literature. But, after giving very sound advice on how to accomplish one’s desire in that direction, Vatsyayana gives even sounder advice, laughingly: "Do not attempt it."

In some ways the distinctions he makes are perfectly sound, and in ways that are obvious. For example, as everybody knows, so many marriages have invited great unhappiness, and often been wrecked, because of the unequal nature of feelings and emotions and passions. Vatsyayana is thoroughly realistic in advising that one should mate with one’s own type, of temperament and feeling, and also physical make-up.

Nor are Vatsyayana’s distinctions of types (physical and mental) pedantic or ludicrous. The Kamasutra’s definite conclusion was that sexual joy is chiefly derived from the feelings and emotions of intimate togetherness, from the magic and the poetry of it, which man and woman can create in each other. Erotic joy is not of linga and yoni alone: it is that of the whole being.

Therefore, what it is also saying is that the texts on kama are of help only while passion is not excited: but once the wheel of passion starts to roll, there are then no texts and no order. And yet, there is order. It is that of self-restraint, which is an essential condition of fulfilling sexual passion. There is still another form of order: it consists in knowing what to do and when. Above all, Vatsyayana says, the order in sexual passion lies in the man doing what, to her temperament and taste, is most conducive to giving the woman the greatest pleasure. "At all times, the man must carefully observe every action of the woman he loves, and so gauge her passion and preferences, and act accordingly, to give her the greatest pleasure." Nothing is to be hurried; nothing is to be forced.

The most remarkable characteristic of the Kamasutra is its attitude of equality between man and woman in matters of erotic love. That attitude is inherent already in the word sambhoga, meaning ‘enjoying together, enjoying in harmony’. Vatsyayana repeatedly says that reciprocity is absolutely essential to the joys of love. He says: "Every lover must reciprocate the beloved’s gesture with equal intensity, kiss by kiss and embrace by embrace. If there is no reciprocity, the beloved will feel dejected and consider the lover as a ‘stone-pillar’. It will result in a highly unsatisfactory union."

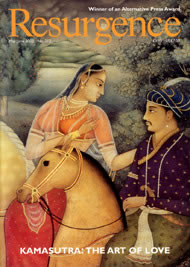

THE POETRY OF the erotic was created, in the middle centuries of Indian history, in stone as well. The mithuna sculptures on the panels of Khajuraho and Konarak temples stand even today as the mystic celebration of kama by men and women. Mystic, as can be seen in the expressions in the eyes and the faces of the men and the women, and in the way their bodies in union are arched. Similarly, that poetry was created in the miniature paintings of different schools. The influence of the Kamasutra on all of them has been profound. A fact of very great significance, in all of them, is the presence always of a third, man or woman, who is not a voyeur. The presence of the third is introduced in the Kamasutra as a means of an even deeper experience of erotic love, whereby the consciousness of the man and woman is enhanced and deepened, their consciousness not of being one, but of their togetherness in the flow of love. The erotic sculptures of India have a dreamlike quality. And Indian philosophy has always maintained that reality is not something hard, fixed, unmalleable. Reality is something that is flowing, malleable, and often intangible, but real none the less. That is true of erotic love between a man and a woman most of all. It is to be created; it does not exist by itself.

What the Kamasutra is saying to us is that sex requires the energy of attentiveness: that is, if sex is not to become a reflexive act of habit. When sex is no more than an outcome simply of habit and proximity, it produces dissatisfaction and distaste. True attentiveness to the other, in sexual relations, requires a disciplining of the mind as much as it requires the disciplining of the body.

Sexual love was regarded as an art, to be cultivated by men and women of taste, requiring a mature understanding of sexual enjoyment — the right place, the right time, the right person, and accomplished practice. The Kamasutra says this to us at every turn.

Often sexuality comes to be used as a weapon of power over the other. Man and woman encircle, overpower and imprison each other in the world of sexuality, which must, in the end, produce their own violence and ill-being. The very first thing that they achieve thereby is the death of sexual pleasure. Thus after every technique of lovemaking has been described, the varied levels of sexual experience have been explored, its medical side researched, and the sexologists have written their prescriptions, the sense of the sacredness of the other shall always remain the emotional foundation of sexual happiness. •

The above is an extract from the introduction to a new edition of the Kamasutra published by Roli Books, New Delhi.