HE PACIFIC OCEAN tsunami was, according to Architecture for Humanity (AFH) founder Cameron Sinclair, the key moment in his network organisation’s short life. Started in 1999 in response to the plight of refugees in Kosovo, AFH has grown from strength to strength as an international grassroots networking movement connecting architects and designers so that they can put their skills to the service of humanitarian crises. Today AFH works alongside aid and disaster NGOs such as Oxfam, the UN, and governmental departments involved in aid and humanitarian support.

Starting with Kosovo, Sinclair and a small band of committed volunteers organised a series of competitions for designing shelter and other crisis infrastructure, providing a platform for architects to work up ideas and plans that meet much more idealistic passions than are allowed within much of the profession’s day-to-day work. Sinclair and others had realised that there were a lot more people out in the design world wanting to get involved and, as he puts it, “make a difference”. Indeed, 220 design teams entered the first competition, which was based on reconstruction in Kosovo. The next project, OUTREACH, arose from the realisation that many of Sub-Saharan Africa’s difficulties resulted from poor access to healthcare systems. The focus was on finding design solutions for a mobile health clinic. The AFH campaign to support small-scale projects like these ran from 2001 to 2005, and included an exhibition in 2003 of the winning projects. Although the exhibition was visited by over 40,000 people, frustratingly for AFH none of the design solutions was realised on the ground.

Elsewhere, however, they have been more successful. A basketful of these ideas, concepts, plans and physical results are showcased in AFH’s inspiring book, Design Like You Give a Damn: a diverse collection of projects, providing either realised or prepared solutions. Many of these architects provide remarkable examples of appropriate, elegant, low-tech and local solutions, showing that design can usefully bring itself to help those most in need.

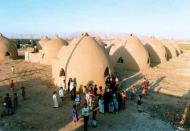

Designs include Buckminster Fuller-inspired domes and other tent-like structures. Equally impressive are Iranian architect Nader Khalili’s super-adobe clay and ceramic shelters for various refugee camps across the Middle East. For unusual materials Shigeru Ban’s paper-log houses and church are possibly the most radical, built in the aftermath of the earthquake in Kobe, Japan. Arguably more modest, though equally effective, is the Safe(r) House, constructed in Sri Lanka with concrete blocks in the aftermath of the 2004 tsunami, looking much like the pre-tsunami Sri Lankan one-storey house but integrating the concrete columns with various protective features against future wave surges. All these designs are pragmatically conceived and, in architectural guise, make use of many of the arguments of the appropriate technology movement.

Similarly, examples in the Community section from the US and South Africa show care in use and economy of materials matched with intelligent design thinking. This comes across in Mason Bend Chapel, a church in Alabama constructed from recycled material including car windscreens, following a design by the late high priest of the US Community Design movement, Sam Mockbee, and his Rural Studio. Another fine project comes from South Africa’s East Coast Architects, Africa Centre for Health and Population Studies, in KwaZulu Natal, built mainly in traditional materials – thatch-work, local timber, plaster, and woven window-shades – and the Buddhist Druk White Lotus School high in the Ladakh mountains. The vast majority of the book’s projects, as well as others AFH have completed elsewhere, integrate sustainability through the need to use the most basic materials available. If pragmatic environmentalism is part of AFH’s portfolio, it could also be said that their ethos is also very close to the ideas of the social justice and anti-globalisation movements.

For more information please visit www.architectureforhumanity.org and www.afhuk.org.