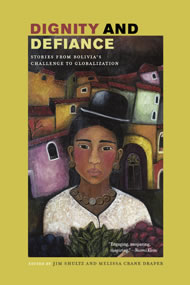

Bolivia is heralded the world over as home to peoples who harbour remarkable courage. Such a capacity is, of course, bolstered and sustained by collective solidarity – but it is ultimately transmitted through the individual heart. Perhaps the most astounding image in Jim Shultz and Melissa Draper’s new anthology, Dignity and Defiance: Stories from Bolivia’s Challenge to Globalization, is a photo of a lone indígena holding back an entire police phalanx with a single slingshot. In the annals of modern bravery this portrait of fearlessness – or, as the case may be, action despite fear – joins the famous shot, taken in 1990s Chiapas, of an Indigenous woman confronting an armed but terrified boy-soldier as only a mother and elder could. Both photos offer the viewer the opportunity to look beyond what too often passes for the norm – to see the truly honest encounter between two opposing approaches to life.

Valour. ¡Animo! Bravura. Such are the themes of this book that reflects on the lives of these long-exploited peoples of the Andean country known for its snow-capped glaciers, llamas, lowland jungle, and over thirty Indigenous cultures. In 2000 Bolivianos rose up against the US-based multinational Bechtel, shutting down the city of Cochabamba three times to stop its takeover of the public water system – in the end, by deft organising and the sheer passion of the people, sending Bechtel scurrying.

Since 2003, mass protests demanding that the government take back control of the gas and oil industries, privatised in the 1990s, have toppled two presidents. In 2005, after centuries of foreign control and home-grown dictatorships, the voters of Bolivia elected one of their own – the Aymara coca farmer Evo Morales – and he has presided over the writing of a new constitution recognising long-withheld rights for the Indigenous majority; the renegotiation and, in some cases, military takeover of corporate-owned businesses to improve the imbalance of reward between multinational and homeland; and the return of stolen haciendas to landless indigenous peoples.

These stories and more are illuminated in Dignity and Defiance, while the historic, economic, and political forces behind them are analysed in depth. The book is the effort of the Democracy Center of Cochabamba and San Francisco, California to provide historical and sociological perspectives to the remarkable movements for justice bursting from the poorest country in South America. Draper and Shultz gathered some of their most knowledgeable and articulate researchers – Boliviano, British, and American – including the economist Roberto Fernández Terán, social critic and activist Nick Buxton, and drug policy analyst Coletta Youngers.

Through eight essays, an introduction and a conclusion, these and other writers explore Bolivia’s water, gas and oil revolts; its most controversial leaf, la coca, which is central to the indígenas as sacred medicine, yet provides the key ingredient for the manufacture of cocaine; the special pressures placed on women by globalisation; the tragic exodus of Bolivianos to pursue their livelihoods in wealthier countries such as Spain and the US; and the economic catch-22s confounding a people struggling for decolonisation after centuries of exploitation from Spanish conquistadores, US and European corporations, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank, the CIA, and their own right-wing industry owners.

The strength of this book is its courage in telling the truth and, amid the statistics and legal concepts, doing so in a compelling manner. The anti-globalisation activist may take offence at the even-handed explanation of the motivations behind certain mechanisms of corporate hegemony such as the IMF and World Bank. Paradoxically, this decidedly academic strategy does not give unquestioned legitimacy to such institutions: rather it serves to highlight the ferocity of protest at the injustices they perpetrate – as well as the complexities and contradictions inherent to any serious effort to build a truly post-colonial world. Naomi Klein calls the book “Enraging, unsparing, and inspiring”, and indeed the swirling of emotion that accompanies this literary witness to the archetypal frictions of our age is to be had, known, and relished. Yet let us be alert to the prospect that – after all the shock, rage, sadness and awe – the end result for the reader could be courage. •