In August 2005, the UK’s national competition for The Big Read was in its final stages. For two weeks, A- and B-list celebrities had been presenting documentaries championing the shortlisted books they most wanted to win. Standing in the middle of my sitting room, buzzing with pride, eyes fixed on the screen, I watched J. R. R. Tolkien’s grandson walk up to the podium to collect the prize for first place. Central to his acceptance speech was the thanks he gave to Ray Mears for the passionate documentary he had made in support of The Lord of the Rings, saying it was by far the best he’d seen on his grandfather’s landmark work. In it, Mears had made clear that his love of Nature and passion for wilderness had been ignited by Tolkien’s trilogy.

I picked up my first copy of The Fellowship of the Ring when I was 12 years old. Isolated from my peers, I saw Middle-earth as the place where my fantasy tribe resided. One by one, those hefty books were proudly jammed into my blazer pocket – a paper dog tag telling the world this read was my reality. At school, the head of English stopped me one afternoon and told me he was impressed by my choice of book and obvious commitment to the mammoth task of getting through all three volumes. And as a result, he promoted me out of the wasteland of CSE to O level English.

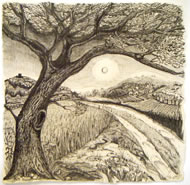

I became obsessed with the vision of Middle-earth I’d built in my mind: its inhabitants, mythology and landscape. I imagined it came close to the medieval world of my forefathers, a world away from the urban sprawl and industrial pollution of the towns and cities I was living in. I often walked alone as a kid, climbing to the tops of great oaks, sweet chestnuts and cedars, discovering them to be quiet, safe spaces away from the stress of school, family and the wider world. Up in the boughs I could sit and think, feel the reassuring movement of wind on wood and look out beyond the confines of where I was to a new horizon. This love of trees in the real world connected easily to the fantastical wooded lands of Middle-earth.

Trees, forests and the life within them form a core theme in Tolkien’s writing – a potent device specifically designed to slow the frenetic narrative of the standard adventure story, creating a pace where the characters can find time to seek a natural response to the relentless drive of progress through technology and war.

Tolkien was fiercely opposed to the idea that his work was an allegory of how he saw and experienced the world, and whilst I wouldn’t have chosen to sit in a room with him and argue the point, it’s clear that everything that was sacred to him on Earth can be found within the poetry and vision of The Lord of the Rings. His views on war (derived from his own experience of the trenches in France) love, spirit and, most importantly, the natural world can all be found within the pages of his seminal work.

Tolkien had a clear distaste for the speed and destructive forces of the society he lived in. He had little time for or interest in industrial progress, seeing it only as the weapon with which his beloved countryside and childhood playground was laid to waste. It is said Tolkein believed that the most evil technology visited on mankind was the internal combustion engine, and he would be horrified to see the development of motorways and roads since his death in 1973.

Part of his response to the speed and growth of an industrial England was in the slow, noble wisdom of the ancient trees that influenced and underpinned so much of his work. The woodlands in his writing are places where danger and safety can be found in equal measure. Fangorn and Lothlórien are forests of ancient power and beauty. In stark contrast, Mirkwood and the Old Forest have been ripped apart by human greed and transformed into shadowy, terrifying places.

Tolkien believed that trees had the same rights as animals and considered them messengers of Nature. In the slow rising to arms of the ancient tree mortals, the Ents, in the final stages of The Two Towers, revenge is meted out on Saruman the White as a result of his destruction of the forests of Middle-earth. Tolkien never really recovered from the clearance of forest and land to create the vast dead spaces serving the creeping spread of urban Birmingham into his beloved Black Country.

Tolkien used his trees as a way to describe the beauty he saw in life: “As Frodo […] laid his hand upon the tree beside the ladder: never before had he been so suddenly and keenly aware of the feel and texture of a tree’s skin and of the life within it. He felt delight in wood and the touch of it, neither as forester nor as carpenter; it was the delight of the living tree itself.”

Through positive, sometimes challenging experiences I’ve transformed my relationship with Nature and ultimately myself. At the centre of this is the way story reveals hidden truths about me and my approach to the world I live in. My work as a writer and workshop facilitator is rooted in the belief that everything we need comes from Nature: food, clothing, shelter, inspiration and creativity. Through my wilderness and writing courses on Dartmoor we provide a space where people can come and be, sometimes for the first time, to sit, write and experience healthy community life.

Fantasy fiction fits well into the entertainment box marked ‘Adventure’, to be taken out on a wet, windy day and used as a means of healthy retreat from the tough drudgery of life. But The Lord of the Rings can be taken to a deeper level. If we choose, we can read into the heart of what is undoubtedly a Nature mythology for our time, drawn from ancient texts, updated, recreated and imagined in response to the unfolding eco-crisis Tolkien witnessed during his lifetime.

For as long as we rely on addiction, war and short-term solutions for our day-to-day survival, this book will remain a key text for our time. If ever there was an extended fable for the causes, effects and solutions of our modern-day woes, the ancient familiarity and timeless wisdom of Tolkien’s epic is it.

The more beautiful and affecting a story, the deeper it will travel into our conscious and unconscious being. The more beautifully crafted, heart-felt and wise, the more power a story has to inspire and energise us to believe that change is possible, that we can build and sustain hope in the darkest of times.

All we have to decide is what to do with the time given to us.