WHEN I WAS A boy, it was my lair, my emotional rehearsal room, my laboratory, my whole domain. Nothing special; just a Chiltern coombe, a scatter of small woods, a lost stream which mysteriously reappeared every seventh winter. But it was where I began to find my worldly bearings. I saw the red rumps of redstarts through my first pair of binoculars, glowing like hot coals. I buried messages for my first girlfriend under a great oak, and grubbed up the altimeter of a crashed bomber in a primrose copse.

More than once, I sat like some teenage Arthur on the slopes, swooning to Vaughan Williams on a portable radio. In some deeply atavistic way, I took possession of that valley, made it my niche. Its own bounds - the soaring hilltop beeches (called Heathen Grove!), that capricious winterbourne, the ancient echoes, the great seasonal flow of birds along the hedgerows I dogged myself - became my bounds too.

Then I cheated on it. I went away. I sold its great animistic wholeness for a mess of details. When I came back (the year Resurgence was started) I found it had been chosen for the route of a four-lane trunk road. It was no longer a place I haunted, but it was still lodged in me like a lodestone. I began to fight for it, but didn't know whether I was pleading for my lost domain, or pursuing the public good. I spoke out for the scarce flowers that bloomed among the beeches and chalk-scrub, but not for my bursting young heart, out there on the hillside to welcome the first cuckoo. The sub-editors of one of the pieces I wrote for the local paper were bolder: "Doomed", they titled it, "The Lost Valley where the Wild Orchids Bloom".

Years later, I spoke out against the road in a public enquiry, and mentioned the colonies of wood anemones that flecked the green lanes in the path of the proposed road. It was a bad mistake, a hostage to fortune. The counsel for the highways authority beamed in gratitude. Wasn't it true that I owned a wood nearby, and hadn't I written very publicly about its wood anemones, and how prolific they were? How could the laneside flowers be of any value when the species was, by my own account, so common locally? I owned wood anemones, he seemed to imply. They must be enough. Enough not just for me, but for the whole community.

He was not being especially devious. He was using the same argument that had come to be the norm in nature conservation: the survival of species counted, scientifically important or "representative" sites counted, but not individual organisms or the feelings of ordinary people towards them.

With hindsight that exchange seems like a metaphor. The possession of nature, its apportionment to the human estate, have been the central questions I've worried over in more than thirty years of writing. And when I was invited by the then Nature Conservancy Council (NCC) to write a personal account of nature conservation in Britain, it was the theme that dominated the resulting book, The Common Ground. Working with NCC scientists was a revelation, a barefoot education in ecology. I learned about the provenance of ancient woodland, about the fragility of the thin skein of life on peat bogs, about endangerment and 'non-recreatibility'.

BUT I WAS BOTHERED about the narrowness of the NCC's remit. "Scientific importance" (whatever that means - what is scientifically 'unimportant'?) was fair enough, but what about social importance, cultural importance? Bringing rare species back from the brink was a crucial part of saving the whole intricate fabric of ecosystems. But shouldn't we also have been striving to maintain the common species, the backbone of natural systems, to keep cowslips part of everybody's experience, to ensure that the song of the cuckoo never becomes a myth, a folk-memory mummified on disc? And what did the 'streaming' of habitats, the notion of Sites of Special Scientific Interest, say about natural places that were not on the list? That they were uninteresting, valueless, someone else's responsibility? There were no such things as Sites of Special Aesthetic or Emotional Importance. Tough luck for you, if your village copse was one of those.

So The Common Ground argued for the importance of the common, and the commonplace, for the centrality of nature in the experience of all humans, not just scientists. Long before the term 'biodiversity' had been invented, it made an implicit plea for 'bioluxuriance', for a widespread richness of nature, both for the sake of humans and for wild organisms themselves. It was a perspective that eventually began to be given consideration by government and planning bodies. In my working life it led, in the 1990s, to Flora Britannica, that botanical Domesday Book, produced by tens of thousands of ordinary British people, about the role of wild plants in their lives. And it led to my buying a small wood in 1981, and attempting to put some of these ideas about the connections between nature and human communities into practice.

HARDINGS WOOD WAS, I think, the first privately owned 'community wood' in Britain, and we had to invent our practice and principles on the hoof. But I'm gratified that a style of wood-life we adopted chiefly out of ignorance and necessity and an uncomfortableness with management structures turned into something that, in retrospect, had a truly ecological shape. We had no fixed management plan, but practised a kind of on-site democracy. We tried (and again naivety and timidity played a part) to echo rather than smother natural processes, and our primitive burrowings and thinnings and trackmakings had more in common with the business of beavers and badgers than foresters.

And, most happily, the diversity of wildlife which resulted was reflected in a huge variety of human activity in what had previously been a dark and empty wood. I treasure the memory of one occasion when these efflorescences of different kinds of life came together: a very serious band of young children set about the absurd but touching task of escorting frogs returning to their spawning pond.

Yet it was not simply the cultural flowering of the wood that left its mark on me, but the wild, self-willed quality of its evolution. The natural regeneration swamped our pointless attempts at planting. Supposedly sensitive plant species migrated round the wood in ways beyond any accounting. All the marks we made were mollified, absorbed, un-tidied up, in the wood's own development plan. It was a powerful lesson, and I now increasingly believe that we need to respect and learn from the anciently evolved wisdom of natural systems, not presume to manage or steward them according to our own principles.

For me, this is partly an ethical choice: all species (ours included) are of equal value. But it is also a practical matter. Our notions of the 'usefulness' of nature - that is usefulness to us - are not only selfish but ignorant. We have scarcely begun to understand the intricacy and reciprocity of the biosphere. It is nameless plankton in the oceans and unglamorous fungi in the soil - none of them the subjects of Green Revolutions or television documentaries - that keep the planet going.

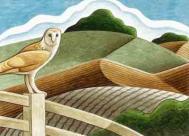

Ironically, this realisation has helped me towards a personal reconciliation with science, a need to know more about other kinds of life on their own terms, not simply as creatures of my imagination. Most weeks now I go to watch our local barn owl, the first I have lived closely with since those childhood days in the valley of the orchids. It is, in the truest sense, a neighbour, and I cannot - as I have done in the past - reduce it to a symbol, make it my emotional puppet. I need to understand how it's getting on here, where it likes to be, what drives its odd reactions to the weather. Already I am learning to glimpse it as other birds might, as a fluctuation of light behind a hedge, as its teetering wings move like divining rods over the grass. But there is much more to do. To bridge that divide between the knowledge of nature as a collection of other beings in their own right and the fierce, luminous presence they have in our imaginations seems to me our next great task.

Richard Mabey is a writer and broadcaster with a special interest in the relations between nature and culture. His books include Food For Free and Flora Britannica as well as his award-winning biography of Gilbert White, and his recent memoir Nature Cure, which was shortlisted for both the Whitbread and Ondaatje prizes. He is Vice-President of the Open Spaces Society and lives in Norfolk.