A Handmade Life is a collection of William Coperthwaite’s wisdom, and his thoughts about education and society, combined with practical, illustrated instructions on making elegant and functional objects.

Coperthwaite – teacher, designer and writer – has spent most of his life on a homestead in Maine, exploring the possibilities of true simplicity. Disillusioned by his early education, he found inspiration in Morris Mitchell, director of his teacher training college. Mitchell “blended cabinet-making and gardening with his leadership of the school”. He also modelled how a teacher can be both educator and learner – something fundamental to Coperthwaite’s own principles for life.

A Handmade Life is loosely structured. It could easily come from Coperthwaite’s musings collected in a notebook whilst out in his canoe at dawn, grouped under headings such as ‘Education/Nurture’, ‘Wealth, Riches, Treasure’ and ‘Life Work’.

Coperthwaite’s approach is “seeking ways to get more people involved in building a better society, one that works for all people everywhere and respects the planet” and he has dedicated his life to this end.

His view is that humanity is currently in such crisis that we need to identify and address key areas where “a small amount of effort [will bring] about a large result”. He approaches this as a design problem. Drawing on philosophy and carpentry, he advocates a design that pays attention to the spatial aspect of society: physical and psychological space within communities and families that best promotes the education of all.

“My central concern is encouragement – encouraging people to seek, to experiment, to design, to create, and to dream...the only hope I see for our survival is to encourage the fullest development of all minds.”

Coperthwaite is scathing about an educational system in which so much money is invested and so little of value actually learned. He had an unhappy education himself, and one can guess at his experience from his condemnation of a system that is largely about shame and failure. For him education, like work, should be an emergent process for all taking part, through creativity and discussion. Teaching by one individual, he argues, is ‘violent’ (from the same root as ‘to violate’) unless it is actively sought: “The cow does not force milk on the calf but waits until the calf is ready to suck.”

He sums up the notion of work succinctly: “The ideal work will develop and utilise the whole person.” Our life work, he believes, is one of our most important choices; for too many, work is simply a ‘necessary evil’ rather than a joy.

Challenging the hierarchical structure of organisations, he argues that direction and supervision should not be permanent roles, but functions carried out by any individual in a transitory way that best meets the needs of the task and the people engaged in it. He extends this thinking to the global economy, and yet always comes back to what we can do as individuals, in our homes and on our land, to create a society “in which everyone wins”.

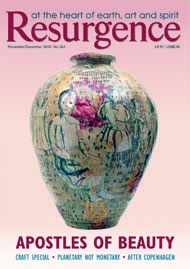

The chapter on beauty is beautiful in itself. Coperthwaite challenges the conventional visual concept of beauty, mentally turning an object this way and that in order to perceive beauty in its making, its history, its purpose and its ready availability. He also ‘sees’ violence in objects through the same depth of enquiry. If there has been suffering in the making of an object, “is it still beautiful?” he asks.

The book concludes with an excellent chapter on simplicity in the best Gandhian tradition, but with a strong Coperthwaite flavour. It offers a thought-provoking challenge to spiritual teachings of non-attachment, asking: “If we choose to place the highest value on simple things, self-made, available to all, would not non-attachment lose its necessity?” He also states (quite comfortably) that he’s happy to take on Gautama, Jesus and Gandhi all at once: “I believe that they would encourage us to seek out the weaknesses in their teachings.”

This is typical Coperthwaite: an eager and avid participant in life, with his Utopia in mind; open to the wisdom of many but blindly following none, presenting his truth and hope with a gentle, humble and deeply convincing voice.