It is tough out there. The economy is uncertain. Jobs are uncertain. The competition is out to get you. It is a dog-eat-dog world.

Except it isn’t, is it? Our Sussex-born lurcher has a passing interest in distant squirrels, but doesn’t show any interest in eating other dogs. In fact, the idea that dogs just want to eat dogs in the first place is actually poor natural science. Dogs, like bees and ants, cooperate with their own kind.

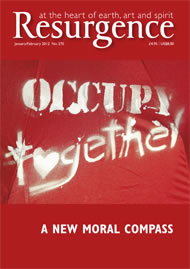

We live in a world where the media, the headlines and the culture scream out competition…get ahead…do it on your own…trust no one…don’t get left behind. But the reality is very different. What keeps things going, what sustains families, what makes work meaningful, what contributes to our wellbeing and what really connects us to Nature is cooperation.

In the wild, working together is what packs of dogs, swarms of bees, schools of fish and flocks of birds do. Flocks of birds are held together, researchers have found, by three simple rules that each bird follows:

Separation – don’t crowd your neighbour.

Alignment – steer towards the average direction that most others are going to.

Cohesion – steer towards the average position that most others will be in.

With these three simple rules, the flock moves across the sky and across the world as if it were a single living thing, creating movement and interaction that would be extraordinarily hard to create otherwise.

In the case of wild geese that are flying in signature V-formation, as each bird flaps its wings, it creates an uplift for the birds that follow. Flying over long distances, if a goose is injured, other birds help to guide it down to safety. Flying in flock, in cooperation, geese have a 70% greater flying range than if each bird flew alone.

These birds are self-organising. But if they went to Harvard Business School, they would probably try and appoint one bird as a leader.

Our business culture feeds off a relentless diet of praise for a ‘John Wayne’ model of heroic businessmen and lone entrepreneurs. Business schools, business bookshelves and business pages are stocked full of references to leadership – but none to followership.

The winner-takes-all economy of rocketing top pay and inequalities reflects the idea that very few are leaders. But if you have a winner-takes-all mindset, no matter how well you do, you will never do well enough – because you are always comparing yourself to others. In Silicon Valley, for example, millionaires report that they don’t feel rich. One says: “Here, the top one per cent chases the top one-tenth of one per cent and the top one-tenth of one per cent chases the top one-hundredth of one per cent.” Another says: “A few million doesn’t go as far as it used to.”

But all economic success is built on the shoulders of others. And it is actually economists themselves who are starting to tear up the rule books of neo-liberal market competition. Eric Beinhocker is one of the best young economists in the UK today. His recent book, The Origin of Wealth, has five times as many references to cooperation as to competition. Cooperation, he says, “is as vital an ingredient in economic development as ‘survival of the fittest’ individualism”.

Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis operate out of the University of Siena, Italy and Sante Fe Institute, USA. For many years, they have been pioneers of a field sometimes called ‘experimental economics’, looking to model human behaviour as it is, rather than as the economics textbooks claim it should be. In A Cooperative Species: Human Reciprocity and Its Evolution, Bowles and Gintis have recently drawn this together and blended it with work and thinking from across the academic spectrum, from ethnography to archaeology and biology, in order to compile an account of the centrality of human cooperation in the evolution of our species. It is a classic text. Our roots as a species are in cooperative action, and it is these pro-social strategies rather than models of pure competition that explain survival and success.

Bowles and Gintis are not the first to argue this – the idea of cooperating in order to compete has been developed over the last three decades in biology since Bob Trivers (‘inclusive fitness’), in game theory by Elinor Ostrom and others, and in political science by Robert Axelrod. In a neat about-turn from his phrase ‘the selfish gene’, Richard Dawkins now points to models where ‘nice guys finish first’. But what is stunning in A Cooperative Species is the construction of a plausible and comprehensive set of proof – including the breadth of evidence they bring to bear, from almost every discipline, and the power and reach of the core methodology they use of drawing on empirical evidence in order to model group behaviour in mathematical and systems terms.

We all need a story. It just turns out that the story we have been told for years – that people are naturally and primarily competitive and self-interested and that life is best shaped around that bleak fact – is bunkum.

Cooperative businesses have always offered proof that you can get on by getting on. Robert Owen cut the hours of his workers from 17 hours a day to 10, and banned the employment of children under the age of 10. Over four years he made a profit of £160,000 and a return on capital of 5%. It is to him, by the way, that we owe the idea of the Cotton Mills and Factories Act of 1819. Cooperatives and trade unions grew up together.

But the economy of the last few decades has stressed growth, profit and competition as the determinants of success. Years before the credit crunch, alternative voices such as James Robertson warned of the dangers of an economy where making money out of money was the most profitable activity of all. It was, Robertson warned, as if a cricket team could multiply its own score tenfold or one hundredfold by betting on the runs that those at the crease were making.

Where financial capital drives business growth, cooperatives, mutuals and family-owned firms tend be a minority form of business. What is interesting now, post credit crunch, is that the context is perhaps better suited to cooperative enterprise than for many a year. The downside economic risks remain huge, and no businesses can be immune to drawn-out recession or worse, but the positive sources of business value are at least now more around innovation, creativity and relationships.

The cooperative sector has significantly outperformed the wider UK economy over recent years. The combined turnover of around 5,000 independent UK cooperatives grew by 4.4% last year to £33 billion, and has grown by 21% since the start of the credit crunch in 2008.

Cooperatives are owned by their members rather than external investors and are organised on the principle of one member, one vote rather than one pound, one vote. Co-ops can be set up under a variety of legal models.

The UK Cooperative Economy 2011, the latest annual analysis of the size and performance of the UK’s unlisted cooperative businesses, reveals that membership of cooperatives has increased with growth of 18% since 2008, to 12.8 million. With one in five of the UK population, there are now more member owners of a cooperative than there are direct personal investors in listed companies on the stock market.

Businesses owned by their employees, such as Suma Wholefoods, now account for £9.4 billion of turnover, while those owned by their customers account for £16.1 billion. This includes The Co-operative Group, Britain’s leading ethical business, whose £14 billion revenue includes food, financial services, pharmacy and funeral services. The Co-operative Bank was recently named the most sustainable bank in the world.

The smaller Midcounties Co-operative, like counterpart cooperatives such as Midlands, Lincolnshire and Southern, has supported new forms of cooperative – including, in 2011, the launch of Co-operative Energy, a household supplier and already a recipient of a Which? Award for consumer action – to offer a trusted alternative to the ‘big six’ energy companies.

The Co-operative Food, a Fairtrade pioneer from the start, has now made a firm and very public commitment to stock Fairtrade produce wherever that alternative exists. The shelves of the East of England Co-operative Society also include the widest range of local foods and beers of any retail chain.

New cooperatives are emerging at a local level supported by a grassroots business advice service, The Co-operative Enterprise Hub, which now operates across the UK – including local food, renewable energy, cooperative schools, village shops and community pubs.

The idea of cooperation is simple. You give someone food when her cupboard is bare and yours is overflowing. She reciprocates down the road when your cupboard is bare, and you both benefit because food is more valuable when you’re hungry than when you’re full.

The cooperative model is good for the economy.

But it is also good for the soul.

Oliver James, writing for Co-operatives Fortnight on the psychology of cooperation, says: “With the ever-increasing threat of ecological catastrophe and the growing risks to the world economy posed by deregulated globalisation, the need for cooperation has never been greater.

“But quite apart from our desire to avoid destroying the planet or economic meltdown, I offer another reason to position cooperation at the heart of our political economy: it will mean we are more likely to live sane, fruitful lives.”

Be cooperative. After all, it is a dog-help-dog world.