Some years ago, when I was living in a tenement block in central London, I saw one evening a neighbour passing with a bucket in her hand. On noticing me she explained, with some embarrassment, that she had been “stealing earth” from a local park so that she could grow something on her balcony. The notion of someone coming out after dark to furtively purloin a container of soil left a lasting impression, but has, over time, begun to take on an added meaning. It is not so much that my neighbour was stealing soil: more that the soil had already been stolen from her. It was like a modern equivalent of that old rhyme about the period of enclosures, the rhyme that berates, not the person who steals the goose from off the common, but the one who stole the common from under the goose. A whole generation, it seems to me, are losing access to the earth under their feet.

Living in London at the moment, where the great tide of development continues unabated, it is hard to believe we are in a recession. Here in the East End I can see the great and rapidly erected blocks of the Olympic fringes sweeping south towards us, whilst the ‘executive estates’ of Canary Wharf continue to spread north. Set somewhere between them, I now pass no less than four building sites on the short daily walk to my children’s school.

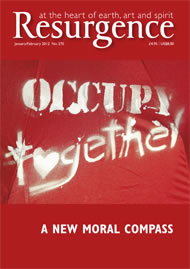

Within this context the growth of community gardening and food-growing projects in the city can be seen as something of a resistance movement: part of a struggle to hold back increasing the development, to maintain our contact with the soil and to meet the need of “the sight of sky and of things growing” that Octavia Hill, founder of the National Trust, thought “common to all men”.

In places this response is suitably anarchic. It includes the guerrilla gardeners planting on neglected and unclaimed ‘waste sites’, and the small community gardens that spring up almost spontaneously on tiny plots of disused land – like the semi-derelict tennis court near me that has been possessed as a garden by the tenants of an adjacent 20-storey tower block. These projects often have a joyously ramshackle feeling, like old allotments or the plotland sites documented by Colin Ward, but there are many more ‘formal’ sites.

Before the most recent round of cuts put an end to such grand projects, the London Borough of Islington invested £1 million in Edible Islington, a scheme to promote food-growing projects in parks, schools and estates. The London Mayor’s Capital Growth project now reports just under 1,300 such sites, with the aim of reaching 2,012 by the start of the London Olympics.

Where there is no soil to start with on sites completely hard-surfaced, some of the approaches have demonstrated considerable imagination. Whole gardens have been created in containers, in raised beds and even in rows of soil-filled ‘grab bags’. On one temporary site in Shoreditch, racks of shelves were constructed and lined with 200 terracotta pots, all lovingly tended by local residents.

But it is not just the availability of open land that is disappearing: so are the skills, the experience, even the culture of cultivating it – a culture that was once prevalent even in areas of the most tightly packed rows of terraced housing, where runner beans were grown and a few chickens kept in even the smallest backyard. Today, by contrast, in our London gardens we have paved over an area twice the size of Hyde Park.

We therefore need projects like The Garden Classroom, which currently operates out of the King Henry’s Walk Garden in Islington, and which aims to help develop new growing sites and to provide the skills – and the encouragement – to run them. The project helps schools and estates to set up their growing projects and, just as crucially, provides in-service training for teachers, and holiday activity schemes such as its Grassroots programme for children.

In pursuing the aim of giving inner-city people the opportunities for a hands-on experience both of growing things and of the natural environment, The Garden Classroom also seeks to make use of every available element of the urban environment, such as street trees or tiny scraps of secondary woodland for forestry projects, or using the local canal for environmental science lessons on a floating classroom.

It has to be admitted that all these are relatively small stirrings at a time when the government is intending to use increased house building to stimulate economic growth and to weaken planning controls on new development. But they are all the more important for that. And what they represent is a deep and vital connectivity with the earth, and a reassertion of that connection for those from whom it has been ‘stolen’.