A by-product of the unprecedented global economic growth of the last 20 years has been the creation of a slew of new, beautifully designed and inspiring museums. In the UK the National Lottery has provided millions of pounds of leverage for capital development, and virtually every major town or city has a new or refurbished museum. Furthermore, the policy of free admission to national museums, introduced in 2001, has enabled increasing numbers of people to enjoy cultural heritage. Culture-led regeneration has transformed areas of industrial decline across Europe. The Guggenheim in Bilbao and developments around the waterfront in Liverpool are but two examples of new cultural destinations.

Yet the limits of the economic growth model have been tested by the financial crises of 2007–9. Many grand projects have proved inherently unsustainable, and within the UK it appears that the days of a landmark scheme in every town are over. There is no guarantee that Western economic growth will return to pre-2007 levels for at least a decade, if at all. Crucially, it is questionable whether growth witnessed in the previous 20 years is compatible with the environmental challenges facing the planet. It has been suggested that if global growth rates continue at the present level, humans would need the resources of three more planets the size of the Earth to sustain life to our current expectations.

Some politicians in the West are tentatively questioning the appropriateness of the orthodox economic growth model. In 2009 a report by Nobel laureates Joseph Stiglitz and Amartya Sen commissioned by French president Nicolas Sarkozy called for new measures of growth that take into account wellbeing. Even in the UK, a stronghold of assertive capitalism, conservative prime minister David Cameron has charged the Office of National Statistics to develop measures around wellbeing and life satisfaction to inform social and economic policy.

A new economics of happiness

An alternative to economic orthodoxy, one in which people and planet matter, can be traced to the radical economist E.F. Schumacher. His book Small is Beautiful (1973) advocated localised economies that accounted for their social and environmental as well as economic impact. Schumacher’s approach influenced Nobel prize-winner Elinor Ostrom, who developed a political economic theory of Common Pool Resources, which highlighted collective action, trust and cooperation.

In the early 1970s the landlocked, autocratic Buddhist kingdom of Bhutan developed a system of Gross National Happiness as a counter to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as a measure of economic wellbeing. Alongside standard economic measures, the index accounted for such social issues as time spent with family, strength of communities and impact on biodiversity. In 2006 and 2009 the radical think tank New Economics Foundation (nef) published the Happy Planet Index, largely inspired by work at the University of Bhutan. This ranked countries not by their economic outputs but by their ability to pursue good environmental stewardship, to foster strong communal relationships and to promote mental wellness. States such as Costa Rica, Colombia and Vanuatu were ranked high, whilst the UK languished in 74th place, with the US 114th.

A revealing measure, which exemplifies paucity of Gross Domestic Project (GDP) to articulate the health of our society, is the Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare (ISEW). The ISEW takes collective expenditure on funding public services such as health and education, the value of domestic labour and volunteering, and ‘service flow’ from consumer durables (leisure time from labour-saving devices!) and sets it against ‘defensive private spending’ –individual spending on commuting, car accidents, personal pollution costs, the collective costs of environmental degradation, and depreciation of natural capital. Whilst GDP per capita has tripled since 1950, the ISEW has not yet doubled. Since 1975, GDP has risen by 80%, but ISEW fell consistently during the 1980s and 1990s. Moreover, environmental costs have increased by 300% since 1950, and social costs by 600%.

A growing and compelling body of research by social scientists shows that increased material wealth has conversely led to a decline in productive social relationships and networks or ‘social capital’. Robert Putnam’s seminal book Bowling Alone (2000) describes an atomised United States where a sense of neighbourliness was falling through the floor. Putnam carried out 500,000 interviews over 25 years and noted that we

sign fewer petitions, belong to fewer organizations that meet, know our neighbours less, meet with friends less frequently, and even socialize with our families less often. We’re even bowling alone. More Americans are bowling than ever before, but they are not bowling in leagues.

Nevertheless it appears that material goods play considerably less of a role in determining wellbeing than our spending patterns might suggest. For many people the pressure to “keep up” in consumption terms has been actively detrimental to real wellbeing and perhaps even a factor in increased risk of mental illness. Or, as psychologist Oliver James puts it, our society is suffering from Affluenza.

Economic growth and the museum mind

For 20 years a belief in the regenerative power of economic growth, for all its positive benefits, has created a rigid, mechanistic mindset in museum practitioners. Much time was spent trying to prove to the Treasury or to local funders that culture contributed to objectives in a range of areas, from reducing crime and improving educational attainment to improving health and contributing to economic regeneration.

This was fine to a point, and whilst it may have been true, for me this approach took much of the joy out of my work. Many museums have not altered their understanding of what it means to do public good beyond following policy agendas, regardless of how progressive they are. Instrumental, deficit-funding policies backed up Byzantine evaluative metrics have made it more desirable that participants in museum activities are more able to enter the labour market than to become good neighbours.

We may be culturally richer than ever before but it is questionable that we are happier. There is a clear challenge to decouple people’s sense of prosperity and wellbeing from economic growth. For museums, I suggest that future efforts should be less geared to producing more and more cultural stuff and should concentrate on the stewardship of our surroundings and better understanding of the role museums can play as connector in civil society.

Happiness at the Museum of East Anglian Life

Aside from being a popular open-air museum with historic buildings, working collections and a beautiful natural environment, the Museum of East Anglian Life (MEAL) in Stowmarket, Suffolk has a strong ethos as a ‘bridger’ of social capital. A true social enterprise, business minded, opportunistic but exuding progressive values and a sense of social justice, it offers a template for the social history museums of the future.

MEAL runs a range of learning programmes, using its historic buildings, landscape and collections to inspire vulnerable people. This includes training and skills development for learning-disabled adults and long-term unemployed people, a resettlement programme for local prisoners, therapeutic placements for mental-health service users, reminiscence training for carers of people with early-stage dementia, and training schemes for young people with behavioural problems. Since 2008 the museum has helped more than 60 people find jobs, provided accredited training for over 150 new learners, and provided new experiences for people who had never before set foot in a museum.

Through observations it was clear that being engaged in these activities at the museum made participants happy. They formed new friendships. They ran each other to the shops, and supported each other in times of personal problems; people who had previously led isolated lives had a new-found confidence to socialise. They began to trust others, many felt they had a status for the first time in their lives, and they became more adaptable. Far from being a refuge, the museum was a springboard for participants.

In 2010 the museum commissioned research using the Social Return on Investment model, which showed that for every £1 invested in its programmes, £4 of social value was created. The museum showed that by working with individuals over the long term in a collaborative environment demonstrable progression was possible.

The programmes MEAL offered could have been carried out anywhere, including on an industrial estate or a forest park, but what made them special was the use of cultural heritage within a museum, which many were encountering for the first time. A Fordson tractor was restored by a group of young people who had left school with no qualifications, and a shepherd’s hut is currently being restored by the work-based-learning team. The success of the museum’s work is not measured by the queues out of the door for blockbusters but by the strength of new social networks created by a shared interest in identity and locality. The museum has seen the wisdom in investing in building social capital as well as with bricks and mortar.

Reciprocity and the core economy

In No More Throw-away People (2003), the American political activist Edgar S. Cahn calls these social transactions part of the ‘core economy’:

Family, neighbourhood, community are the Core Economy. The Core Economy produces: love and caring, coming to each other’s rescue, democracy and social justice. It is time now to invest in rebuilding the Core Economy.

Cahn called upon policymakers not to measure the economic or social outputs of investment but the reciprocal transactions of a community enabled by strong relationships and ties.

Building a resilient organisation based on the relationships and bonds between individuals should be grist to the mill for museums. In his 13 volumes of studies of village life in East Anglia, George Ewart Evans, a pioneer of English oral history and co-founder of MEAL, showed that reciprocity was key to the functioning of an agricultural village right up until the Second World War:

The Miller and the Millwright, the harness-maker and the tailor show how the old village community was dovetailed together by the nature of the work.

Yet policymakers are still preoccupied with symptoms rather than cause. At the moment the only way of measuring the success of our work is to examine what participants don’t do – they don’t claim benefits, because we’ve helped them get jobs; they don’t see their GP as much, because they are more physically and mentally healthy – but we need to find a new measure or at least a way of articulating that the quality of people’s relationships makes them happy. In Happiness (2007) Richard Layard noted: “Public policy can more easily remove misery than augment happiness.”

Authentic happiness and museums

In his book Authentic Happiness (2000), the American positive psychologist Martin Seligman wrote that we would be a far more successful society if we enabled mental wellness rather than concentrating efforts on treating mental illness. He talks of stages of happiness:

First, the Pleasant Life, which consists of having as many pleasures as possible and having the skills to amplify the pleasures in order to generate positive emotion.

Second, the Good Life, which consists of identifying signature strengths, and then recrafting work, love, friendship, leisure and parenting to use those strengths to have more flow in life.

Third, the Meaningful Life, which consists of using your signature strengths and the pleasure derived from Eudaemonic Flow to do things in a cause which are greater than self.

To simplify, one can derive positive emotion from seeing a beautiful work of art or gain eudaemonic flow from engaging in an absorbing activity (the volunteers who come in every weekend to maintain MEAL’s steam traction engines attest to this). However, in order to foster powerful or meaningful experiences, museums should create a landscape that not only enables participants to engage in the issues of the day but also helps them contribute to society through acts of kindness and altruism.

Museums and the conditions for happiness

Museums are in a great position to create meaningful positive experiences based on cooperation and reciprocity. Social history museums in particular are invariably at the centre of their communities, and many of their objects are familiar and even comforting. Even when displays challenge assumptions or are contested they are done within an environment or institution that still engenders a high degree of trust.

Since 2009 MEAL has began to explore, through three exhibition programmes, how it might interpret its collections in the context of subjective wellbeing and happiness.

First, the When Were We Happy? online exhibition tried to discern historic levels of happiness in the Suffolk village of Stowupland. This was micro-history in true history workshop fashion. Working with a local branch of the Women’s Institute and the village school, the museum used nef’s Happiness Index and compared village life in four periods in time: 1851, 1901, 1951 and 2001. It examined the quality of environment and biodiversity, time spent with family, and the strength of community life, as well as solid social history measurements such as standards of public health, economic wellbeing and education.

The English have never taken a particularly subtle view of the history of rural communities. We have either a bucolic image of the countryside, of rosy-cheeked children skipping around thatched cottages, or one of grinding poverty, of life nasty, brutish and short. However, the picture in Stowupland was more mixed. There are more clubs and societies in the village in the 21st century than ever before, but from interviews with local people who were alive in 1950 there was a perception that the village was more social half a century ago. There were more single-parent households in 1900 than there are now, and these days life expectancy is higher and there is more opportunity to spend time with friends and family. The ingredients for happiness exist today, but the interviews with local people showed nostalgia for the past and a perception that back then there was more ‘community spirit’.

Secondly, the museum presented Happy Days, a project that collaborated with 7- and 8-year-olds from Lavenham Primary School. Using objects from their own lives, the children were asked to design a ‘happy day’ and describe it through poetry or prose. Overwhelmingly (and with no prompting from museum or teaching staff) the children chose objects that represented relationships with their parents and friends and playing outdoors. They then chose objects that would have reflected a ‘happy day’ for a Victorian child, and in this context the objects referred to the dinner table and festivities. At no point did the children mention their own material possessions in the context of designing a ‘happy day’.

Finally, in 2010 the Trust exhibition examined the ties that had bound communities in rural Suffolk over the last 100 years. It drew on research from Layard’s Happiness, which noted that people’s wellbeing was associated with predictability, the number of friends within a 15-minute walk, and opportunities to connect with others. The challenge for rural communities in the 21st century is to retain and celebrate these qualities within a highly mobile and diverse dominant culture.

Happiness is good for your health

There is an emerging body of work in UK museums exploring the wellbeing impacts of engagement in heritage for people using clinical health services. For many years art therapy, ‘arts on prescription’ and reminiscence work have augmented clinical therapies, especially with mental health service users and dementia patients. Museums have used partnerships with clinical practitioners to further explore their role in developing ideas and policy around public health and wellbeing.

The University College London (UCL) Museums & Collections Heritage in Hospitals project carried out controlled research to identify wellbeing outcomes for inpatients engaged in handling museum objects. This research (using the PANAS methodology – Positive Affect Negative Affect Scale) showed a significant enhancement in the happiness of patients within hospital wards following activities with university collections. UCL is developing Generic Well-being Outcomes metrics to help museums better quantify the benefits of such an approach.

In Manchester, the Who Cares? programme at the Whitworth Art Gallery brought together artists, clinical practitioners and patients to create a therapeutic space within the permanent galleries as “a stimulus for curiosity and exploration, reflection and meditation”.

The Happy Museum Project

Drawing on the experience of exploring the nature of social capital at MEAL, established work on health and wellbeing in other museums and a desire to face the impending environmental challenges, the Happy Museum Project was initiated in March 2011. Its aim is to challenge museums to adapt their behaviours to promote high-wellbeing, sustainable living. Its clarion call, The Happy Museum, written by nef and museum practitioners, noted:

Our proposition is that museums are well placed to play an active part, but that grasping the opportunity will require reimagining some key aspects of their role, both in terms of the kinds of experience they provide to their visitors and the way they relate to their collections, to their communities and to the pressing issues of the day.

The Happy Museum argues that museums have innate qualities that can inspire a re-imagining of a society that values cooperation and stewardship as much as it does economic wellbeing. Museums are both popular and trusted. Apart from the ubiquitous gift shop, museums have little to ‘sell’ visitors other than learning and enjoyment.

In a world that seems increasingly saturated by advertising, a trip to a museum is an all-too-rare opportunity to find sanctuary from commercial messages. This is no trivial matter, for not only is materialism strongly implicated in our present environmental difficulties, it is increasingly recognised by psychologists as a serious source of dissatisfaction, unhappiness and mental ill-health.

To fully exploit their advantages to play a part in a transition to a low-carbon world of new economic and social values, museums must address behaviours that have rightly or wrong become ingrained. Rather than just being tellers, museums should accept that they don’t have all the answers and should aspire to become truly participatory institutions enabling co-production involving museum and community. A recent study by Bernadette Lynch on participation in UK museums noted that despite examples of very good working practice, “real engagement that goes beyond ‘empowerment-lite’ faces hitherto unseen obstacles that inevitably result in the dissatisfaction of both staff members and community partners”.

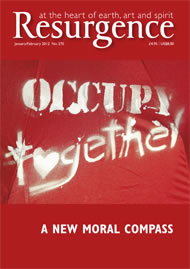

Moreover, from time to time museums should eschew their objectivity and actively lead campaigns. Rather than viewing themselves as neutral spaces, they should realise their potential as a place for encounters and as a rallying point or refuge for the community.

The Happy Museum concludes with an eight-point manifesto, which suggests ways in which museums can lead the transition to a low-carbon, high-wellbeing future. These include

• Adopt nef’s Five Ways to Well-being: Connect, Be Active, Take Notice, Keep Learning and Give

• Pursue mutual relationships

Find ways to have more mutual relationships with communities, supporters and visitors. Consider the possibility of becoming a mutual organisation, or of running your organisation as a cooperative.

• Value the environment, the past, the present and the future

Value and protect natural and cultural environments and be sensitive to the impact of the museum and its visitors on them. Focus on quality and don’t be seduced by growth for its own sake.

• Measure what matters

Counting visitors tells us nothing about the quality of their experience or the contribution to their well-being. Ask your audience how your work affects them emotionally; don’t wait for someone else to design the perfect metrics – talk to people, understand what makes them feel happier, measure that.

• Support learning for resilience

Museum learning is already all the things much orthodox learning is not: curiosity-driven; non-judgmental; non-compulsory; engaging; informal; and fun. The people needed in the future will be resilient, creative, resourceful and empathetic systems-thinkers, exactly the kind of capacities museum learning can support.

A few UK museums have made a start in this process. The M Shed in Bristol is developing a permanent display about greening the city, working with Transition groups and green charities. Bridget McKenzie’s Museums for the Future programme for a consortia of museums in the South East of England points the way for them “to become agents in forging a more environmentally sustainable future”. The Happy Museum Project itself is commissioning several projects that will put the principles into practice, with the aim of creating a community of practice akin to the Transition Network in local economies.

Of course many museums do appreciate their position at the heart of their communities and many combine scholarship, stewardship, learning and a desire for greater participation. What the Happy Museum Project is trying to do is to show that the context is now different. Climate change, pressures on the planet’s finite resources, and awareness that a good, happy society need not set economic growth as its most meaningful measure offer a chance to re-imagine the purpose of museums. Museums need to realise their role as connector, viewing people not as audiences but as collaborators, not as beneficiaries but as citizens and stewards who nurture and pass on knowledge to their friends and neighbours.

For more information: www.eastanglianlife.org.uk <www.eastanglianlife.org.uk>; Twitter: tonybutler1 Blog: tonybutler1.wordpress.com